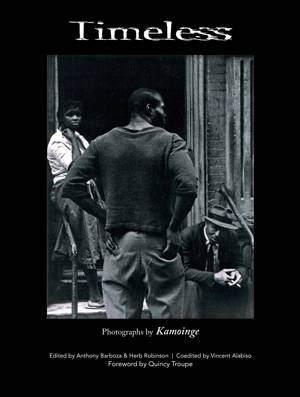

Timeless is the proof. At nearly 400 pages, it’s the biggest survey of the collective’s work so far, with portfolios by 14 founding members followed by a lively selection of work by members from the past five decades. Beuford Smith, Eli Reed, Radcliffe Roye, Ming Smith, and Gerald Cyrus are among the standouts, but few of the photographers here got the recognition their talent deserves. Still, “timeless” might not be the best word to describe their pictures. Predominately black and white, overwhelmingly sincere, even the most recent work falls into the tradition of the concerned photographer, which is probably why Kamoinge was featured in the opening exhibition of Cornell Capa’s International Center of Photography in 1974. Barboza isn’t alone in trying out other strategies, but much of the work here is solidly, shamelessly rooted in the past – in DeCarava, Cartier-Bresson, Robert Frank, Helen Levitt – and the better for it. When Beuford Smith writes, “I photograph as passionately and humanely as possible,” he’s speaking for many of his colleagues. Working almost exclusively with black subjects, they closed a distance most photographers never even acknowledged, and inspired a generation. Collectively, their vision is rich, textured, and, unlike so much recent photography, grounded in real, tough, and sometimes astonishingly beautiful life.

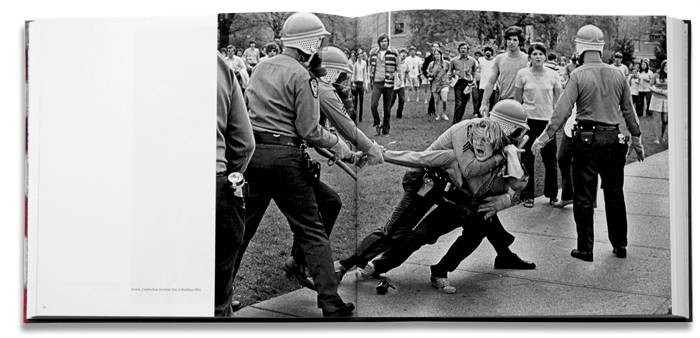

For another thick, juicy slice of the real, pick up Ken Light’s What’s Going On? 1969-1974 (Light2 Media), a collection of the photojournalist’s earliest work, documenting the riled-up, politicized counterculture in which he came of age. Light was 18 in 1969, when he started photographing his peers in the anti-war movement, and 21 when he became a staffer for the Liberation News Service, prime conduit for the burgeoning underground press. His book – with endpapers that reproduce letters from his FBI surveillance files – starts out looking like a student radical’s version of Joe Szabo’s Teenage and ends up with a sequence of furiously engaged reportage that recalls Danny Lyon and Larry Fink.