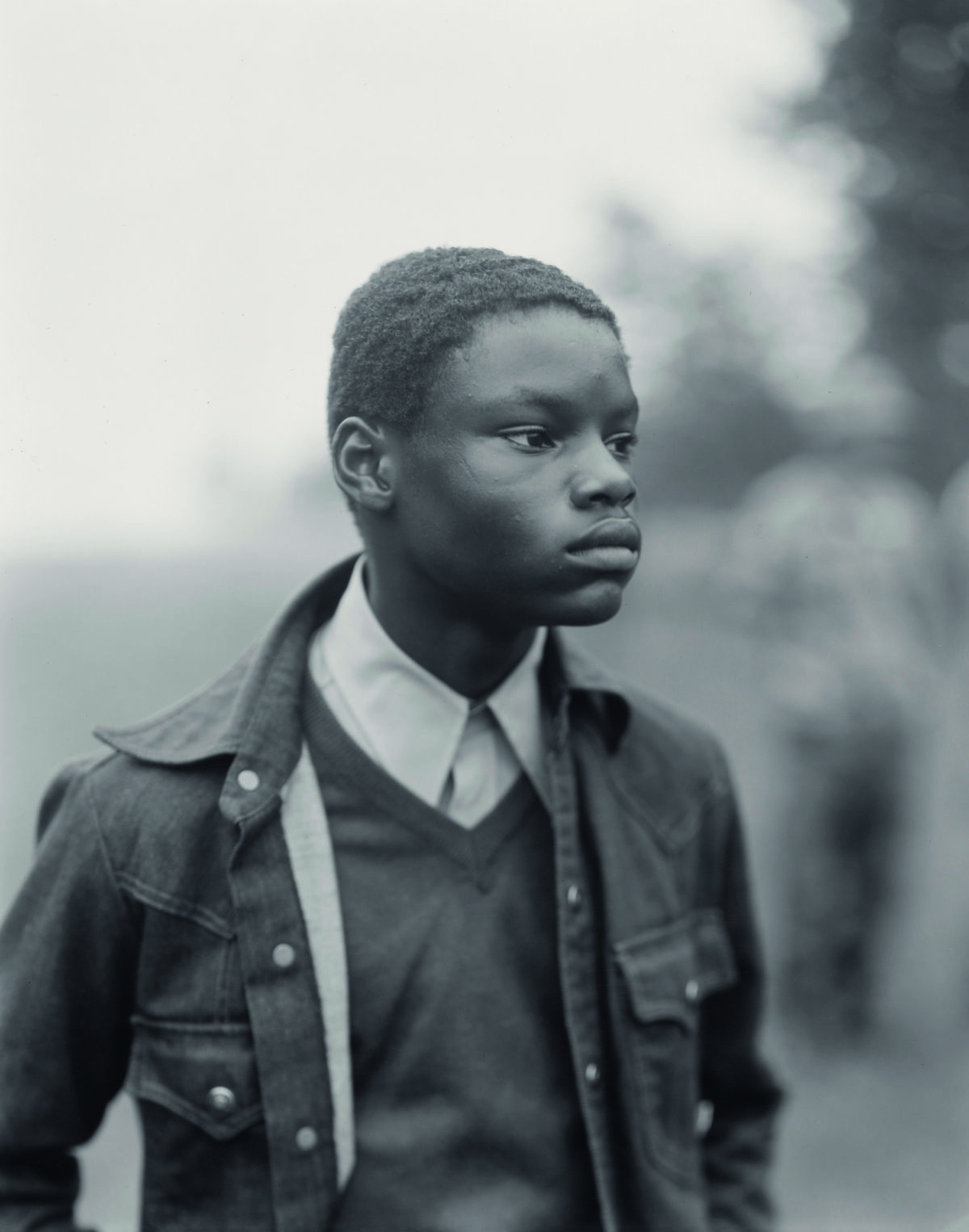

Book and photo fairs, which often overlap these days, are great sources for titles you might not find anywhere else. Here are three worth searching out in the new year: Ethnos, an exhibition catalogue published by Munich’s Bernheimer gallery, gathers a choice group of Irving Penn’s marvelous studio portraits from Dahomey, Peru, Morocco, New Guinea, and Cameroon in what could be seen as a companion volume to Worlds in a Small Room(1980). Timeless, elegant, and endlessly absorbing, Penn’s pictures-—including a number of variants and previously unpublished images—are reproduced with exceptional care and an eye on the collector’s market for both books and prints. Eduardo Serafim’s self-published I Wish You Were Here (at eduardoserafim.com), a weirdly mesmerizing sequence of fuzzy landscapes and interiors hacked from surveillance cameras, aims at a broader audience for the found image. Discovering how easy it was to access (and even redirect) surveillance cameras via computer links, Serafim downloaded 100 views of offices, residences, and intersections from all over the world, sent them as postcards to random addressees, and then reproduced them here in all their dumb, degraded glory. Katsu Naito made the arresting black-and-white pictures in West Side Rendezvous (Wild Life Press) in the early 1990s, when practically the only people on the streets of Manhattan’s Meatpacking District after the butchers went home were transvestite hookers and hustlers, ready for another sort of business. Naito’s portraits of these characters drive his book, and many are knockouts, tough and affectionate, recalling Leon Levinstein, Diane Arbus, and Peter Hujar. Posed outdoors in various states of undress, his subjects display a poignant mix of bravado and desperation, probably giving far more of themselves than they do to their customers.

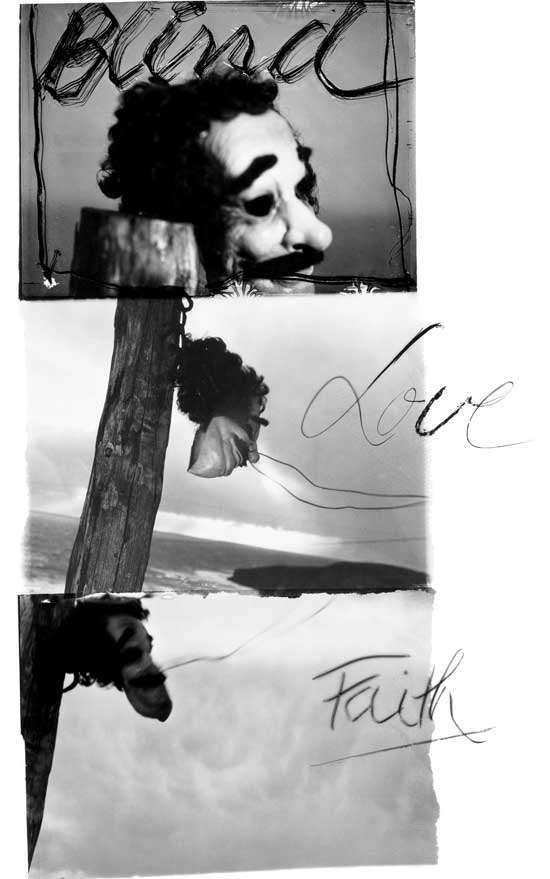

Photographic images were always key elements in Robert Rauschenberg’s assemblages, but they were rarely his own. Borrowing freely from the pop-culture image bank, Rauschenberg made his most potent early collages and combines out of pictures appropriated from magazines, newspapers, and books. After a series of copyright suits brought by disgruntled photographers, he began using his own photographs in the 1980s, but the results were often disappointing; even the most hackneyed mass-media image had more resonance than one of Rauschenberg’s snapshots. So Robert Rauschenberg: Photographs 1949-1962 (D.A.P.) comes as something of a surprise, if not a revelation. Although his photographs are nowhere near as original as his art, they’re solid examples of a midcentury American style that zeroed in on the vernacular, the ephemeral, and the everyday. There are echoes of Walker Evans, Harry Callahan, and Aaron Siskind here, but Rauschenberg has a confident looseness all his own and his pictures feel effortlessly right. Along with telling portraits of friends and lovers, including Jasper Johns, Cy Twombly, Merce Cunningham, and John Cage, there are pictures of his Fulton Street studio with early works in progress on the walls. This mix of personal and art history is hard to resist, but you really get the full impact of Rauschenberg’s sensibility in his photographs of a bare light bulb, a tattered window shade, or a pair of old boots in a Roman flea market. His appreciation of the interplay of common materials—found image and found object, raw and refined—anticipates the provocative juxtapositions in the career-defining Combine works he began making around this same time. But the photographs aren’t just footnotes to Rauschenberg’s art and life—they’re a vital element of both.