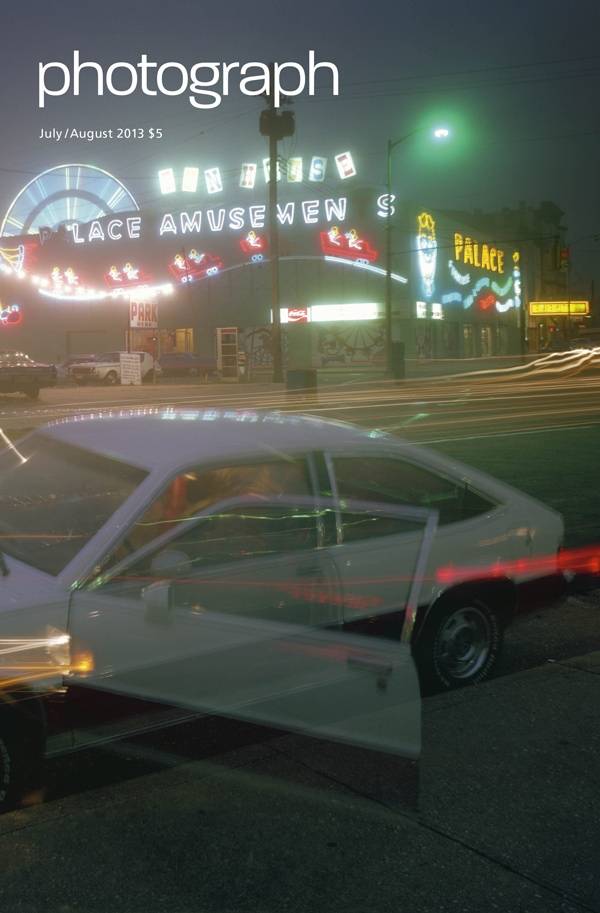

It’s a truism of photography that it embalms the past, freezing moments and transforming “this is” into “this was.” But the notion of the photograph as a mini-memorial doesn’t begin to describe the complicated life in perpetuity of pictures. In the case of Joe Maloney’s photographs of Asbury Park, New Jersey, we have to consider how events have further transformed “this was” into “this might be.” When Maloney, who grew up in New Jersey, was shooting in the late 1970s, American photographers from Joel Sternfeld to Stephen Shore were taking color to the street, giving up agitprop black and white for Warhol day-glo, neon, and polyester pastels. William Eggleston had his Memphis, Mitch Epstein had Martha’s Vineyard, and Maloney had Asbury Park, the working-man’s ocean-front paradise. The landmarks are all there in their long-haired, late-model muscle-car glory: the boardwalk, the Casino and the Stone Pony, Bruce Springsteen’s launching pad. In the show at Rick Wester Fine Art (through August 16), now ensconced in new and roomier quarters on 26th Street in Chelsea, you can almost feel the summer heat and smell the zinc oxide. Maloney’s pictures shift gears between the parking lot precision of Stephen Shore and the anecdotal energy of early Joel Meyerowitz. As with the cover image (Asbury Park, New Jersey Palace Amusements, 1980), some of the best pictures feel like snapshots, pictures you might have taken to stick in a shoebox or a scrapbook, just so you could pull them out later and say, “Yeah, that was a blast.” Which leads us back to the unusual relation of these pictures to time and events. Sure, the photographs look nostalgic, and they occasionally hint at the changes that were coming for the Jersey Shore—the economic decline of the area, hastening the neglect of the shorefront around Asbury Park. But by the early 2000s, the pictures had a new valence as the shore underwent a renaissance that made Maloney’s images seem less like a memory and more like a celebration. And then Sandy hit, and the devastation it caused has transformed once again the impact of these images. Says Rick Wester, “Joe wasn’t out to make the perfect picture, and he certainly wasn’t an anthropologist, but he was and is interested in using photography as a way of documenting his sense of a particular time—what the colors were like and how they interacted with the place and people to produce something indelible. I like to think of these as rock and roll pictures.” Given the likely economics of flood relief and disaster insurance, the shore may never look the same again, but if it does manage to revive a Springsteen energy, Maloney’s pictures may have served as both inspiration and prophecy, a medium through which New Jerseyans were able to look forward by looking back.

Categories