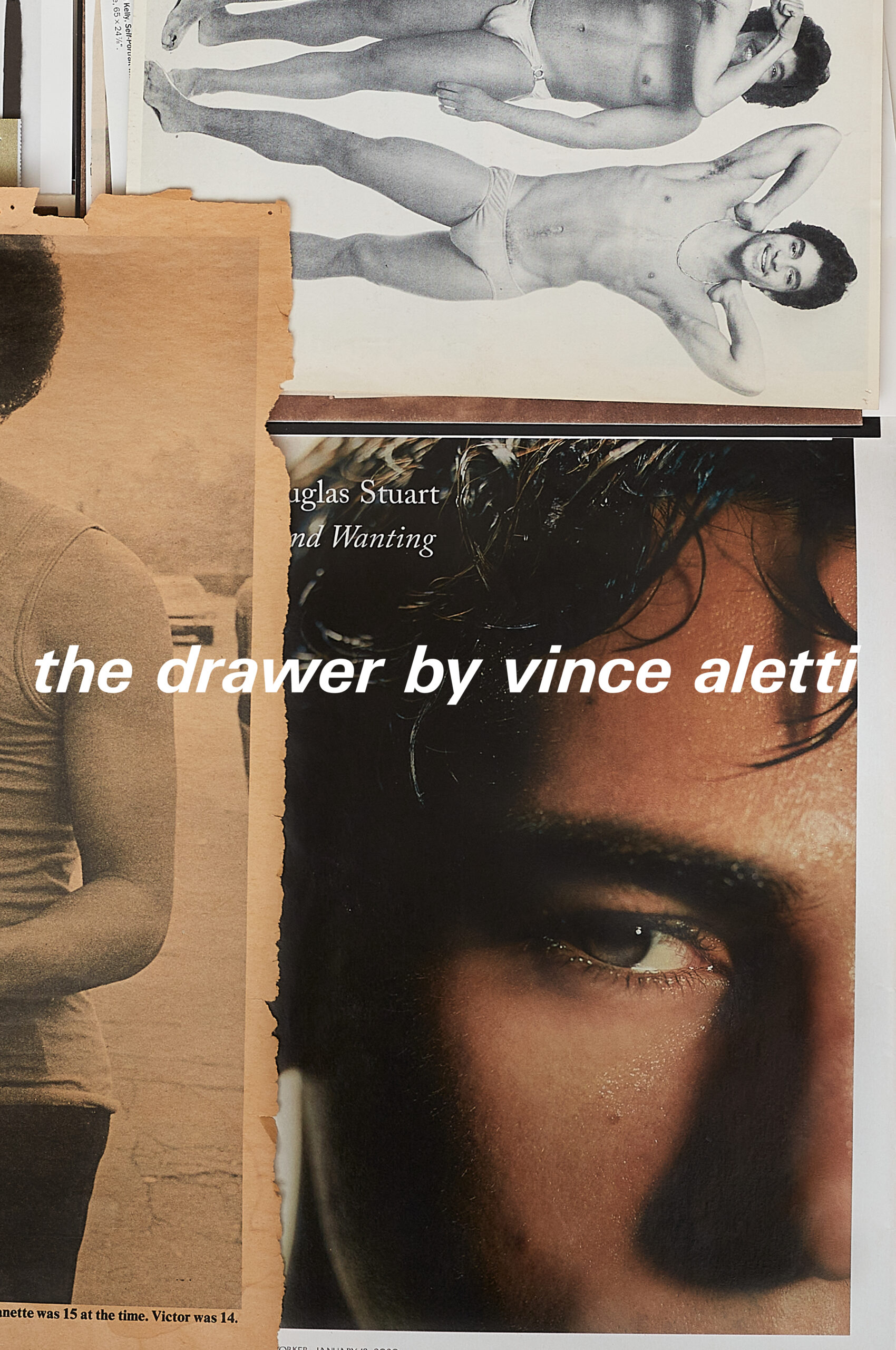

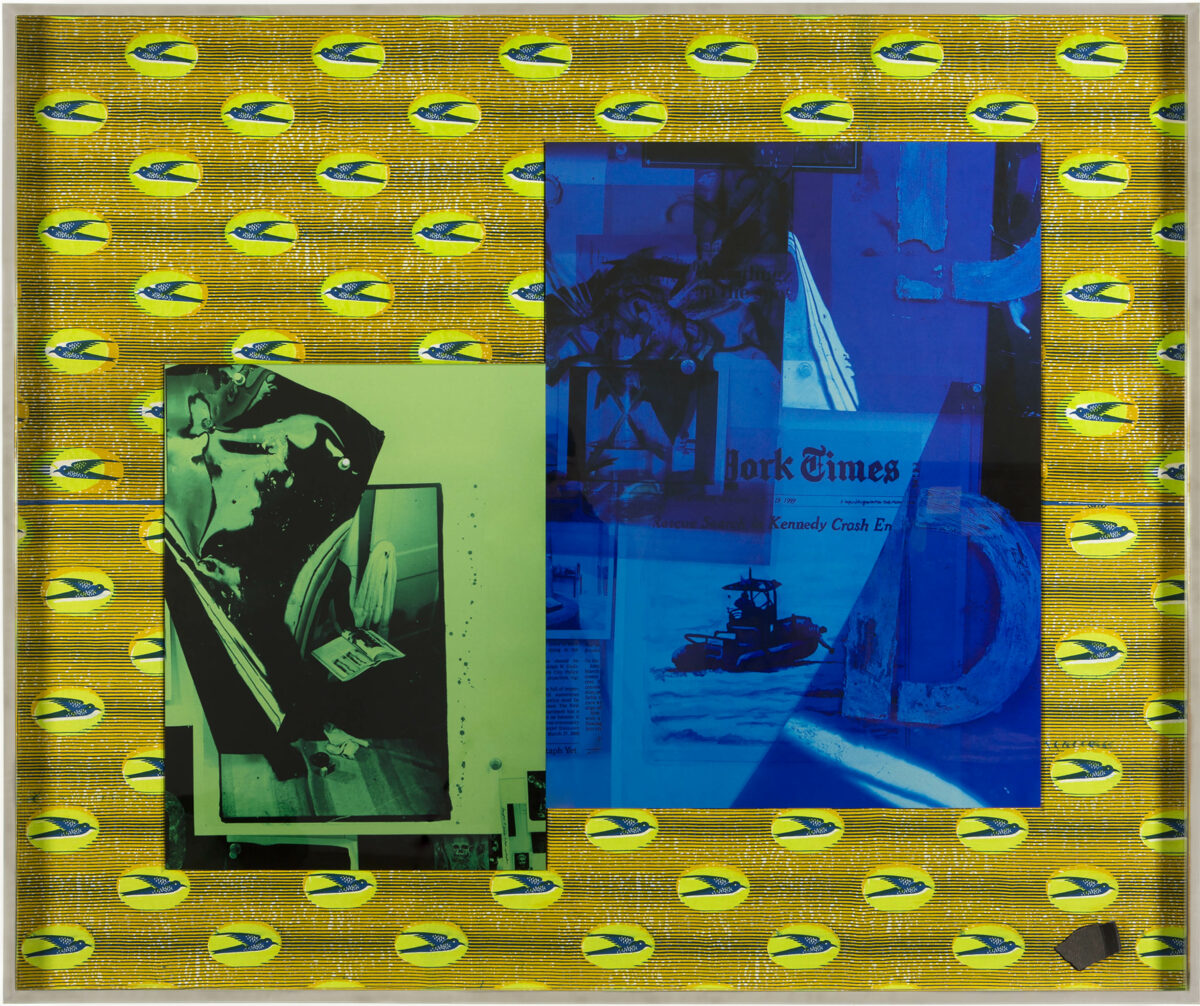

Vince Aletti has been writing about photography for various outlets, including this one, for decades, producing reviews and essays characterized by a spirit of generosity and a tangible curiosity about what photographers do and how they think. He’s also curated numerous photography exhibitions – for the ICP, for galleries in the U.S. and abroad, and, we come to find, for himself, in the drawer of a cabinet in the East Village apartment he’s lived in for more than 40 years. Aletti’s apartment is famously filled to the rafters with books and magazine he’s collected over the years. Less well known was the drawer in question, which contains pictures torn from magazines and newspapers he’s discarded, as well as other ephemera. A large percentage of the images are of men, but there are also pictures of people like Susan Sontag, or of paintings, sculptures, drawings, and gallery announcements – images that caught his eye, that moved him, inspired him, gave him pleasure. It’s a kind of cabinet of curiosities, in flat-file form. He thought of it as an ever-evolving, private pursuit until Bruno Ceschel, the founder of Self Publish Be Happy, spotted the contents of the drawer and envisioned a book. And so on a single afternoon, with the help of photographer Anushila Shaw, Aletti arranged and re-arranged the contents of the drawer into one satisfying or provocative arrangement after another until 75 compositions had been created and photographed. Each page means something to him, but there is no text in the book to dictate what it should mean to readers, who are free to see relationships, contradictions, or tensions among the pictures in The Drawer.

Jean Dykstra: How did the idea of “curating” a single drawer come about?

Vince Aletti: The cabinet is something that I’ve had for almost as long as I’ve been in this apartment. It’s basically a catchall in a lot of ways. There’s a drawer for mail stuff – stamps and envelopes – another for posters, and one for editorial material. It’s kind of varied but this one drawer contains things that I’ve held onto, that I pull from when I’m looking for stuff to put on the wall, because I’m always tacking things up or putting things on the refrigerator. And then after two weeks I take it down and it ends up in that drawer.

JD: Are you constantly curating/reorganizing it?

VA: Always. It was basically just for me, not for anyone else, until Bruno saw what was in there. I never close it without arranging what’s on top, so that when I open it again I’ll be happy.

JD: Do you ever have to cull things out?

VA: Oh yeah. There are times when I realize I can’t close it anymore, and there are a number of boxes that have taken up the slack of that drawer.

JD: How often do you open the drawer and look at it?

VA: At least once a week, sometimes twice, sometimes more. I always open it up for a reason. I’m looking for something that I know I put in there, something that I know I can use to spark a new project.

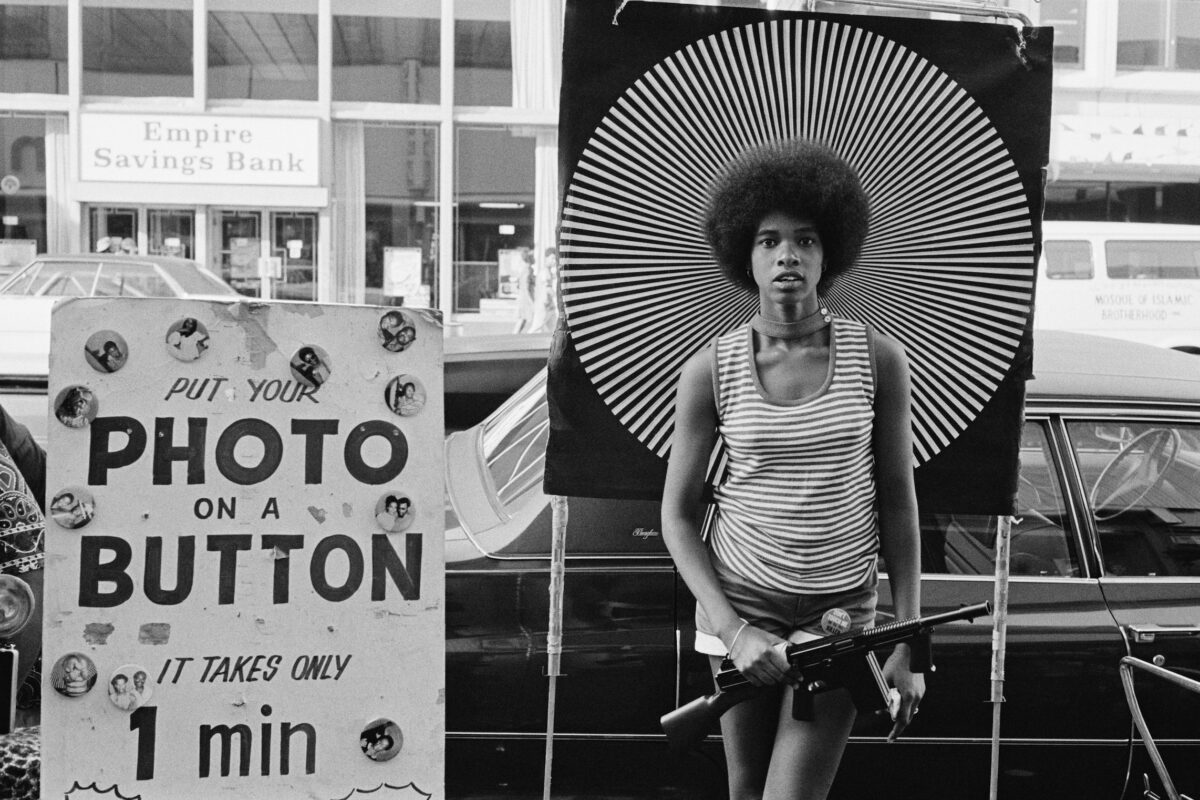

JD: Were there themes that emerged as you were shooting the book? One is obviously men, but were there other themes, or ones that you weren’t expecting?

VA: Not really. I don’t surprise myself that often. But people come up again and again that I’ve always been interested in: Irving Penn, Richard Avedon, Andy Warhol, Susan Sontag, people or things that have always been on my mind, and when I find a new picture relating to that person or theme, I want to keep it. The drawer is basically only pictures from magazines, or something that I’m not going to hold onto otherwise.

JD: I was interested in to see a lot of sport imagery in the book.

VA: Well, that gets back to men again. I realize one of the sections I never fail to look at in the Times is the sports section, because there are some really great photos there. I’m always amazed at what people do on the field or the court – the places that they get to just astonish me, the height somebody can jump, the attitudes when they’ve won something. I’m always looking for that.

JD: When did you first begin tearing pages out of magazines and holding on to them?

VA: Probably when I was in college and had a bulletin board. That became a place where I could kind of define myself, and it was always by pictures. So it would be something I found in a magazine, typically something by Andy Warhol, or from Harper’s Bazaar. Some of that stuff I still have, especially things from fan magazines or teen magazines. When I was in college I realized it wasn’t wrong for me to be looking at Sixteen Magazine, because I was such a fan of the Beatles and the Rolling Stones, and there were a lot of great pictures in every issue. I was so caught up in Pop art at that point, so all of this was an extension of Warhol in a way, but also related to my complete absorption in Motown records, and the Beatles and the Rolling Stones. That’s when I started writing about music.

JD: Speaking of magazines, you subscribed to House & Garden magazine when you were in middle school. What was it about that magazine that was appealing to a middle schooler?

VA: God knows. I remember announcing to my classmates that I wanted to be an interior decorator when I was nine years old, and that was from reading those magazines.

JD: Back to the book, it’s hard to believe you arranged and shot all of 75 pictures in a single afternoon.

VA: It was so much about spontaneity for me. As soon as one shot was done, I moved all that stuff out of the way and did another one. I really enjoyed it. It’s also been interesting for me to read some of the connections that people have made between the pictures on a page that – believe me – I did not make in any conscious way. It’s part of what I loved about doing the book.

JD: And there is no text in the book – no introductory essay, no captions.

VA: Right, no explanations. It’s a picture book. I wanted people to look at the work and not have titles or names attached to it.

JD: A fair amount of the images in the book are of paintings and sculptures – they aren’t all of photographs.

VA. Right. The drawer is a reflection of everything I look at. When I was doing photo tours for ICP, I would take people around to galleries. The idea was that we should go to photo galleries, but I always made a point of saying: Look, we’re right next door to a really great painting show. I’m not going to take you there but you really need to go there after we break up. You can’t just look at photography. You’re not seeing everything you need to see, but you’re also not giving yourself the opportunity to open up your ideas beyond a particular medium. Everything is informing everything else.