Gideon Mendel is a member of the young generation of a group known as “struggle photographers” in South Africa, photojournalists who came of age during the fight against Apartheid in the 1980s. His images gave a vivid picture of what life was like in that tumultuous time, and his ongoing project Drowning World expands his activist concerns. It is on view at the Eli and Edythe Broad Art Museum at Michigan State University through October 16.

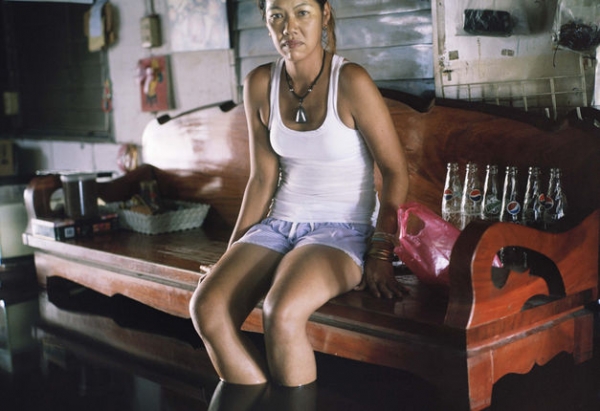

Lyle Rexer: On a certain level, these are conventional environmental portraits taken in different locations around the globe, but they are very disconcerting. Where did the idea come from?

Gideon Mendel: I was deeply concerned about climate change, thinking about the world my children would live in, but I was troubled by the conventional imagery, of polar bears and melting arctic ice – all very beautiful, but I wanted something more direct and personal. In 2007 there was massive flooding in the U.K. and India, and I had the idea to shoot people who were affected, where they were affected, before the waters receded. That’s the pattern I have followed. Sometimes people are half submerged in water, and sometimes they are up to their knees in mud, trying to clear out their houses. I meant the portraits to be disconcerting.

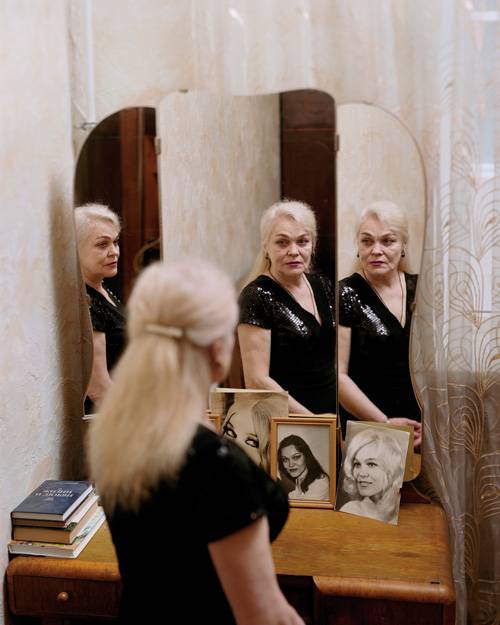

LR: It’s surreal, really, their gazes are so calm in these utterly chaotic situations, almost stoical. And the light and color in the photos are often stunning.

GM: The calmness is partly an artifact of the camera I use. A Rollei film camera is difficult and expensive, and I use slower film with a comparatively long exposure. There’s a theatrical aspect to using it, and the act of looking is different: you look down into the camera, not straight through it. All this strengthens a connectedness to my subjects. These are suspended moments in people’s lives, when there is little they can do. There is a shared sense, as well, that with climate change, we are all in the same leaky boat. As for the aesthetics of it, the water gives an atmospheric light and color. I confess I do love it.

LR: Compared to your earlier work in South Africa, this is a departure in tone. Living in Yeoville, for example, was raw and impassioned. Who inspired you?

GM: Back then, Omar Badsha and of course David Goldblatt. I worked in his darkroom, and he was tough on me. But I have to say, I am impatient with the myth of the heroic photographer. We were trying to photograph important things that were touching us in different ways. We were also egotistical and trying to make careers. But for me, photography was a way to communicate a politics and to have a voice on issues that were clearly black and white, right and wrong. That marked me. I am cursed by the desire to do good.

LR: But so little of the good that photographs might do is under the control of the photo-grapher.

GM: I’m not cynical but traditional photo-documentary, it is tired and depleted. And in many situations, taking a picture is the wrong thing to do. I went to Calais to photograph in a transit camp, where migrants were waiting for a chance to cross the channel to England. The conditions were bad and people clearly did not want their photos taken. They were ashamed; this was not how they wanted to be represented. In the midst of it all, a group of 30 photographers showed up from England and began firing away. The people said, “You photojournalists come here and take pictures and have us tell you our stories, and you say it’s going to do something but it’s just a lie.” It made me hate photography. So I wound up picking up trash. I took objects that might be meaningful in some way later on, rather than photos.

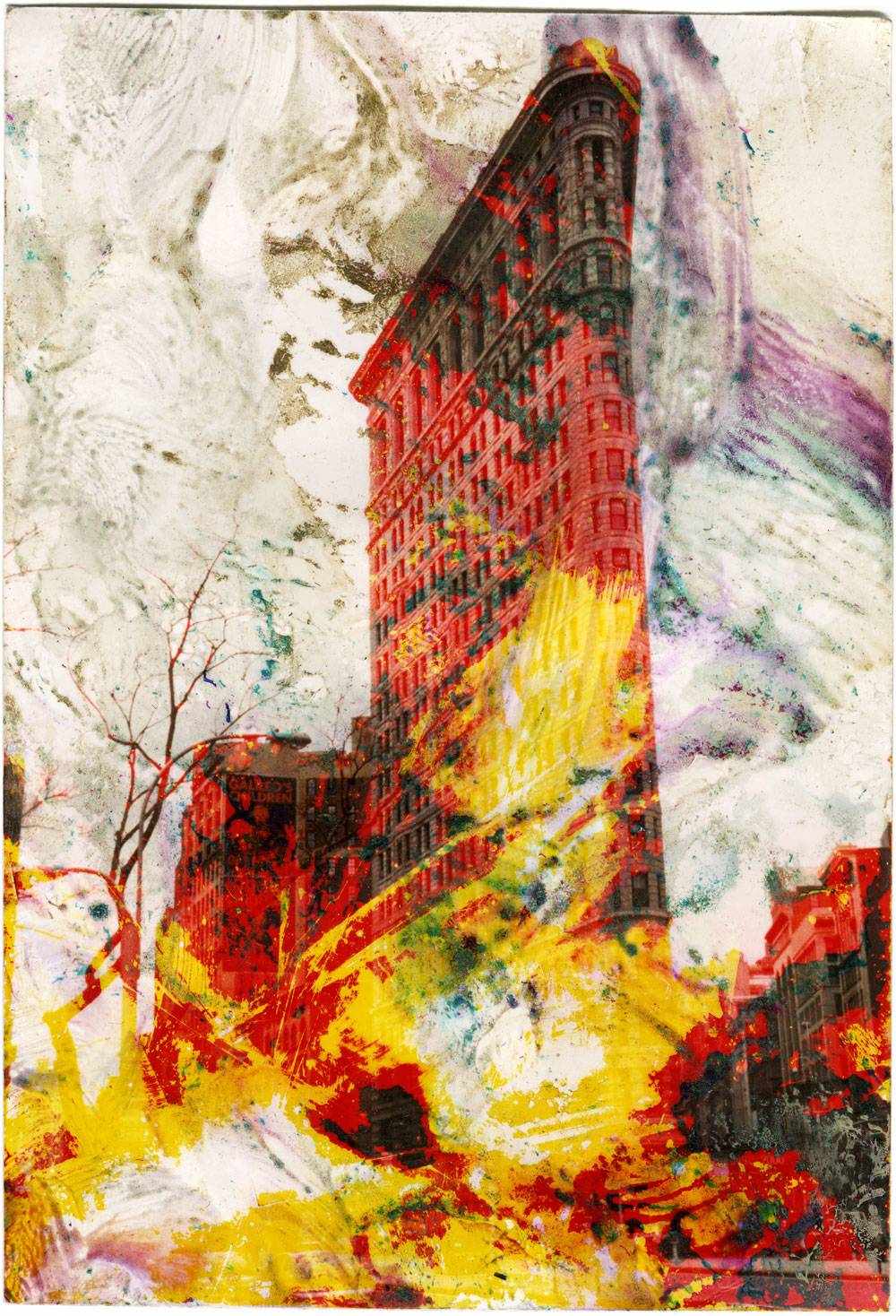

LR: I notice in the Broad exhibition that there are artifacts in addition to the portraits, damaged photographs you found or got from people in the flood areas. This kind of appropriation and display strategy is more appropriate to an art audience, as is the larger dimensions of the prints.

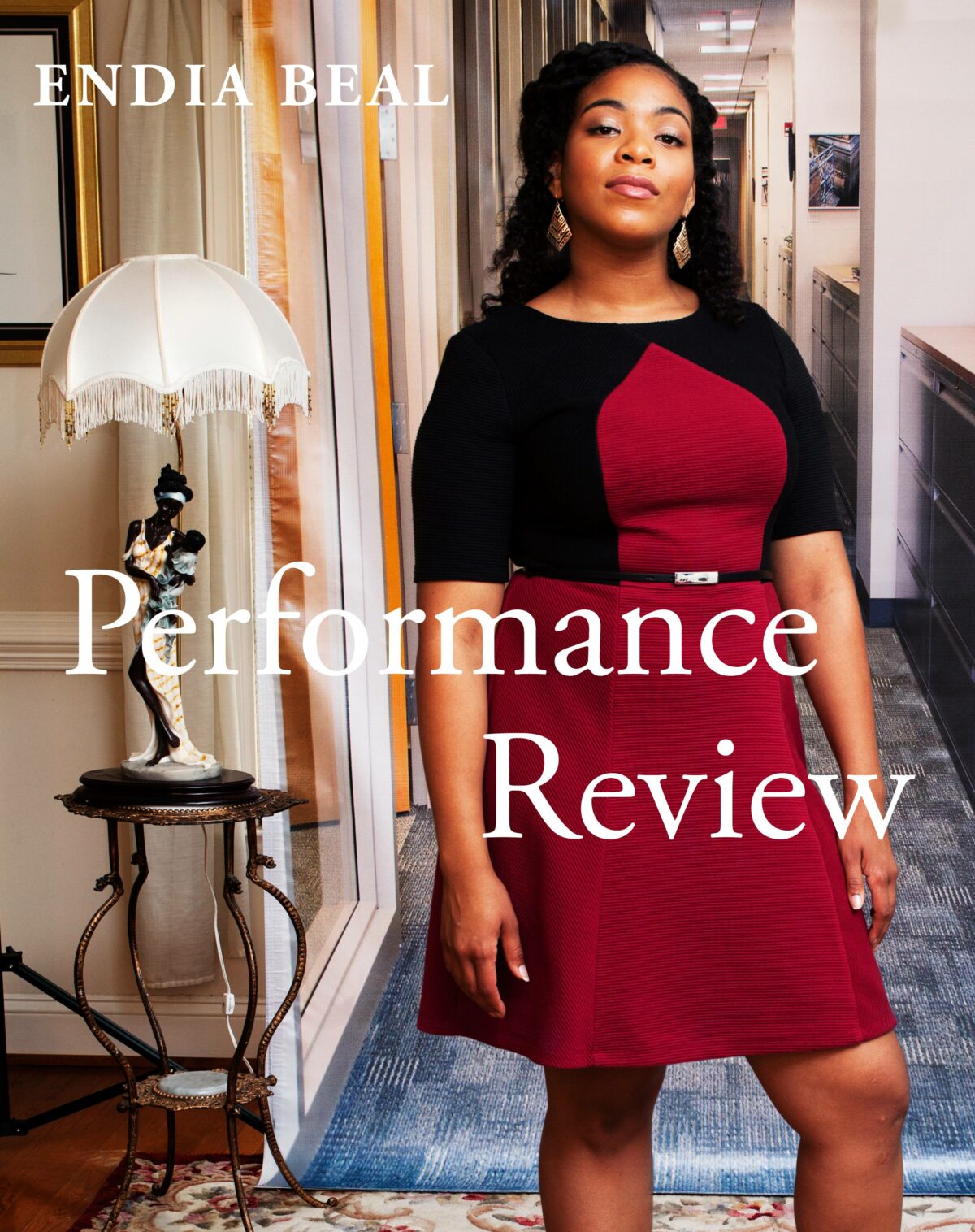

GM: It has taken quite a long time, but after 35 years working in three different pigeonholes – documentary, activism, and art – my work is being taken seriously in an art context. Re-angled, you might say. A museum such as the Broad, which is a great facility, is a different creative space for me. It is a place to experiment in ways that you don’t or can’t do in the other areas. For example, at the Broad I display the found photographs in a vitrine, but I also rephotographed some specific images and blew them up to hang. The dialogue they create with the portraits is really what the show is about.

LR: There is also some practical benefit in addressing an art-world audience.

GM: Given what has happened to paying outlets for documentary work, the movement of photographers into the art world strikes me a bit like all the embassy people trying to get out of Vietnam on those few helicopters in 1976. It can appear that desperate.

LR: That said, you remain a committed activist looking for ways to change things, as you say – cursed by the desire to do good.

GM: My work with HIV is a good example. You mentioned to me that my book on HIV in Africa was the first work of mine you saw. I went through an evolution from using black-and-white images and text to color images to more direct activism. My current project is called Through Positive Eyes, a collaboration with the UCLA Art & Global Health Center. It involves training people with HIV to use the camera to tell their own stories, rather than have someone else make those decisions for them. We work together, and to date 122 people are part of the projects, coming from many different countries. Some of the results are going to be shown in Durban, South Africa. After four decades of the HIV epidemic, the point is to reduce the stigma, which remains one of the toughest barriers to fighting the disease.