This is an Erwin Olaf year, with retrospective exhibitions at museums in Den Haag, his native Amsterdam, and Shanghai; a new monograph covering his career (Erwin Olaf: I Am (Aperture), with Olaf’s commentary on his photographs); and an exhibition in New York at the Edwynn Houk Gallery through June 1. All these events offer ample opportunity to look beyond the surface of his stylish tableaux to consider the deeper currents of isolation, self-scrutiny, and existential longing they explore.

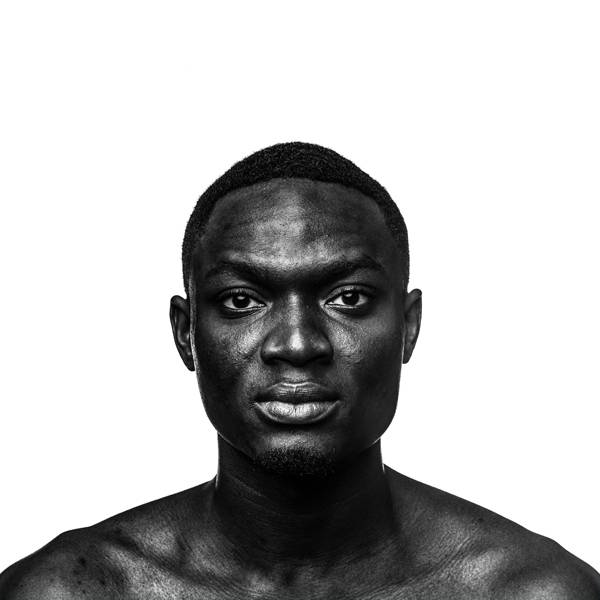

Lyle Rexer: I want to start right off the bat with a central problem – or let’s call it a conundrum – of photography today, and that is the portrait. Of course, we’re taking millions of pictures of ourselves and others, but on the artistic side, what is it you think you’re doing when you take a picture of someone you don’t know, for any reason that isn’t strictly personal? Does it come down to a negotiation between appearance and idea?

Erwin Olaf: For me, the most difficult thing to do is to make a registration of another person. I get a lump in my stomach like lead. You don’t have influence or a relationship with the person, so the best thing you can do is be objective. You look for a way to stay on the surface but also to go inside. You examine the state of the face, the person’s eyes, the small gestures, the way the muscles move slightly, and of course the influence of light and cropping to add to the intuitions you receive. These restrictions are the main reason why I feel more comfortable in my personal projects, where I can fantasize, or let’s say, I can create a world of my imagination. I prefer to use the word imagination.

LR: Fair enough, but imagination carries its own demands, and these, as I see so clearly from your recent work, can be extremely rigorous. It is not a simple liberation.

EO: It takes so much more time and attention to translate what you feel and imagine into an image that is exactly what you want. For example, I concentrate intently on who I cast for my pictures. It is perhaps my most important decision. I have ideas for how the characters – for that’s what they are – should look, and how they should convey particular emotions in the situations I set up. I am trying to make entire movies in 125th of a second. Beyond that, every choice is crucial. In the self-portrait I shot for the series Palm Springs, in which I am standing by a swimming pool, if I move back ten centimeters, the picture is a failure. If the person in the pool moves ten centimeters toward me, the picture fails; the idea does not come through. And having transitioned from analogue to digital in 2007, I find color management to be absolutely crucial.

LR: The idea of that photograph being you looking at a younger self, or you looking at an earlier image of desire. I often tell my students that tableau photography is the most naked you can be as a photographic artist because all your choices and your imagination are on display. You can’t hide behind reality, accident, or the novelty of a “subject.” If your dream cupboard is bare, it’s bare.

EO: After the 1980s, documentary looked like art, and I think the prevalence of tableau photography, and the interest in my work especially, is a reaction against that trend in documentary. It’s in the atmosphere. But the risk is that it can look like kitsch. When I look back over work I did some time ago, I want to approve it, but I have to say to myself it is possible to make silly things.

LR: Well, there is something to be said for maturity.

EO: Excuse me, I notice you sound like you are having trouble breathing.

LR: Yes, I’m having bronchitis and a bad attack of asthma.

EO: So we understand each other.

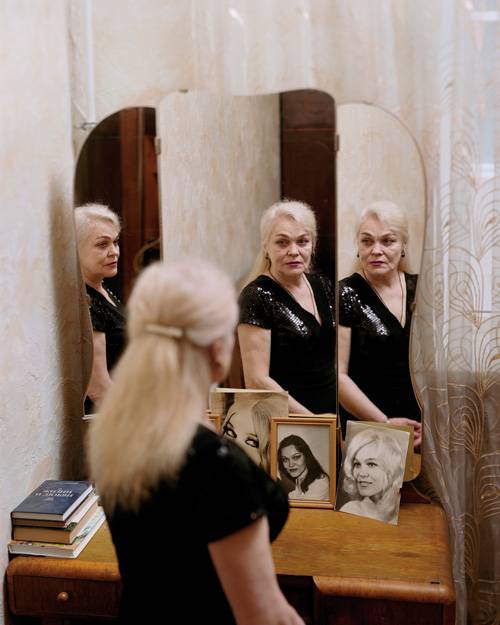

LR: We’re in similar leaky boats when it comes to our pulmonology. That’s one reason your triptych [I Am, I Wish, I Will Be, 2009] resonated with me so much.

EO: In I Wish, I put my head on the body of someone I know from my gym. My present self was my 50-year-old self. And the third is me with an oxygen tube. That’s the physical future I am facing.

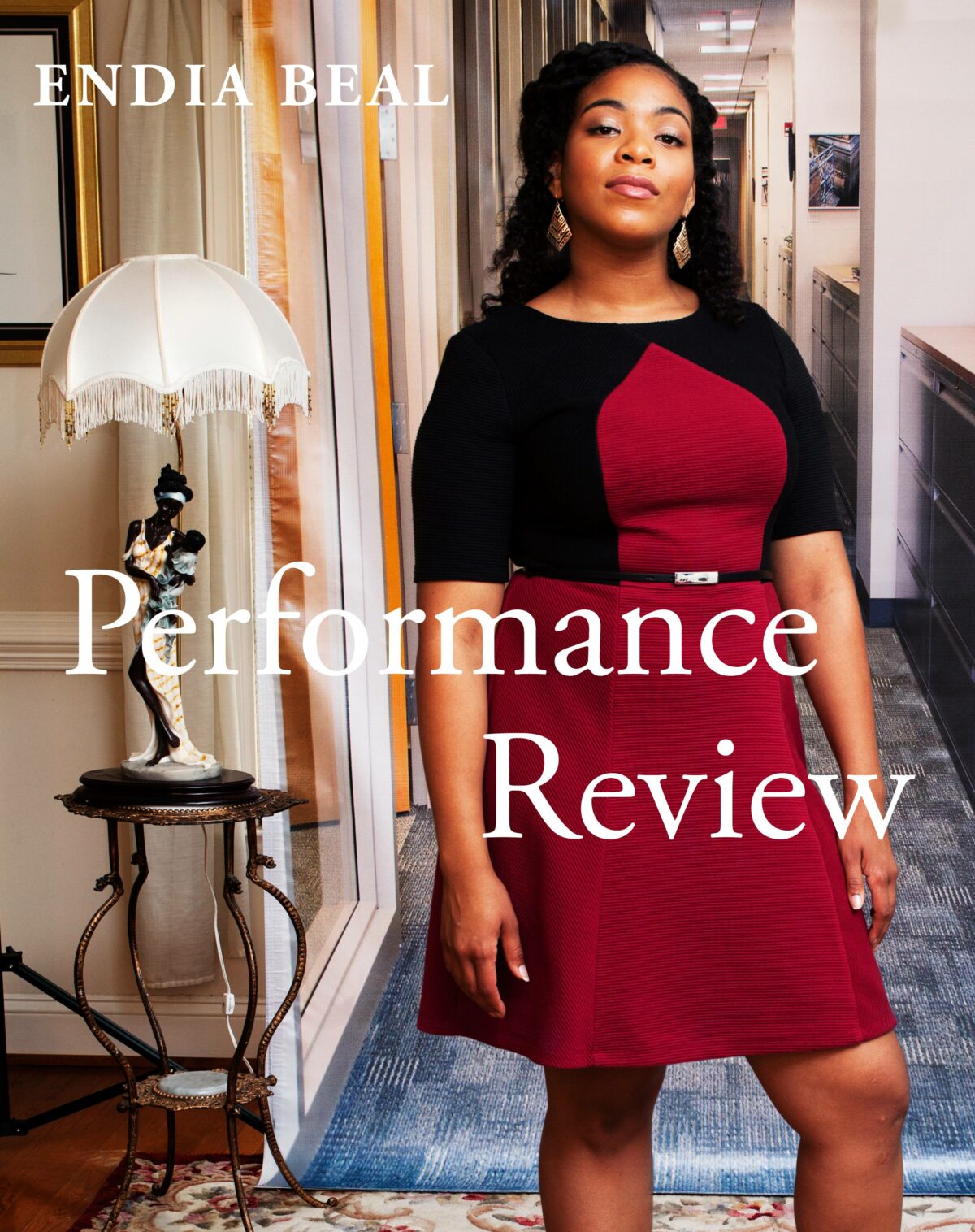

LR: Since we are on the subject of mortality, I am fascinated – even inspired – by your transit from the Roma portraits of the early 1990s through the fashion-oriented work to the series on different cities that began in 2012 – Berlin, Shanghai, and most recently Palm Springs. It seems you have come not exactly full circle but to a place where simple settings and quasi-captured poses can yield the most reflective of intimations.

EO: I learned photography as a documentary practice, and the Roma photographs were my farewell to that approach. I staged the objects of designer and architect Borek Sípek in real settings with real people. I wanted their rawness. I’ve gone through these phases or moments since then. In 2002, I had an important exhibition that received zero stars. I had to rethink. I was an alpha male who was so interested in conquering the world, and I knew how to attract attention. But I was growing up, and things were happening in my personal life. I had to ask myself – why do I make these things? For whom? Not for dollars, not for others, but for me. As a result, I wanted to get deeper inside myself, to explore emotions and try to translate those into images.

The Berlin series – in fact all the pictures shot in specific cities – came from a desire to get outside the studio, to bring in more of the world. I am an avid consumer of news, and politics is part of my daily diet. In Berlin I was struck by a city of freedom that has had to learn from its past. Of course, I was inspired by the interwar artists like George Grosz and Otto Dix, but during the shooting, I also noticed the presence of children, the power of the child in Berlin and Europe. That felt like a positive development. In Shanghai, I encountered the city of the future, like the Jetsons, with 24 million people living vertically, but it was also a city being torn apart, with people displaced by rapid change. In my photographs many of them seek to hold on to traditional forms, and in a crowded city they remain isolated.

LR: So is Palm Springs, then, your vision of America?

EO: I wanted to do something in the United States, but I needed an approach. The photographer Jeff Dunas finally convinced me to do a master class in Palm Springs in 2018, and it was really positive. I have strong emotions about the country and wanted the project to come from the bottom of my heart, but I don’t want to be anti-anything at this point. Of course, I saw beautiful period architecture, but I didn’t want the project to be about that. I found a strange city in the middle of the desert, and that seemed somehow typically American, but not at all in a negative way. I wanted this to be my starting point. So Palm Springs refers to 1950s style in period clothes and décor, but mixed with the reality of today, the reality of climate change and a multiracial city, among other things. The series is a form of time travel. I am talking to you as a guest in my reality, which is now, not the past. I can’t tell you exactly what each of the stories means or even what they are. I can only invite you in to the images and leave it to you to discern a significance.