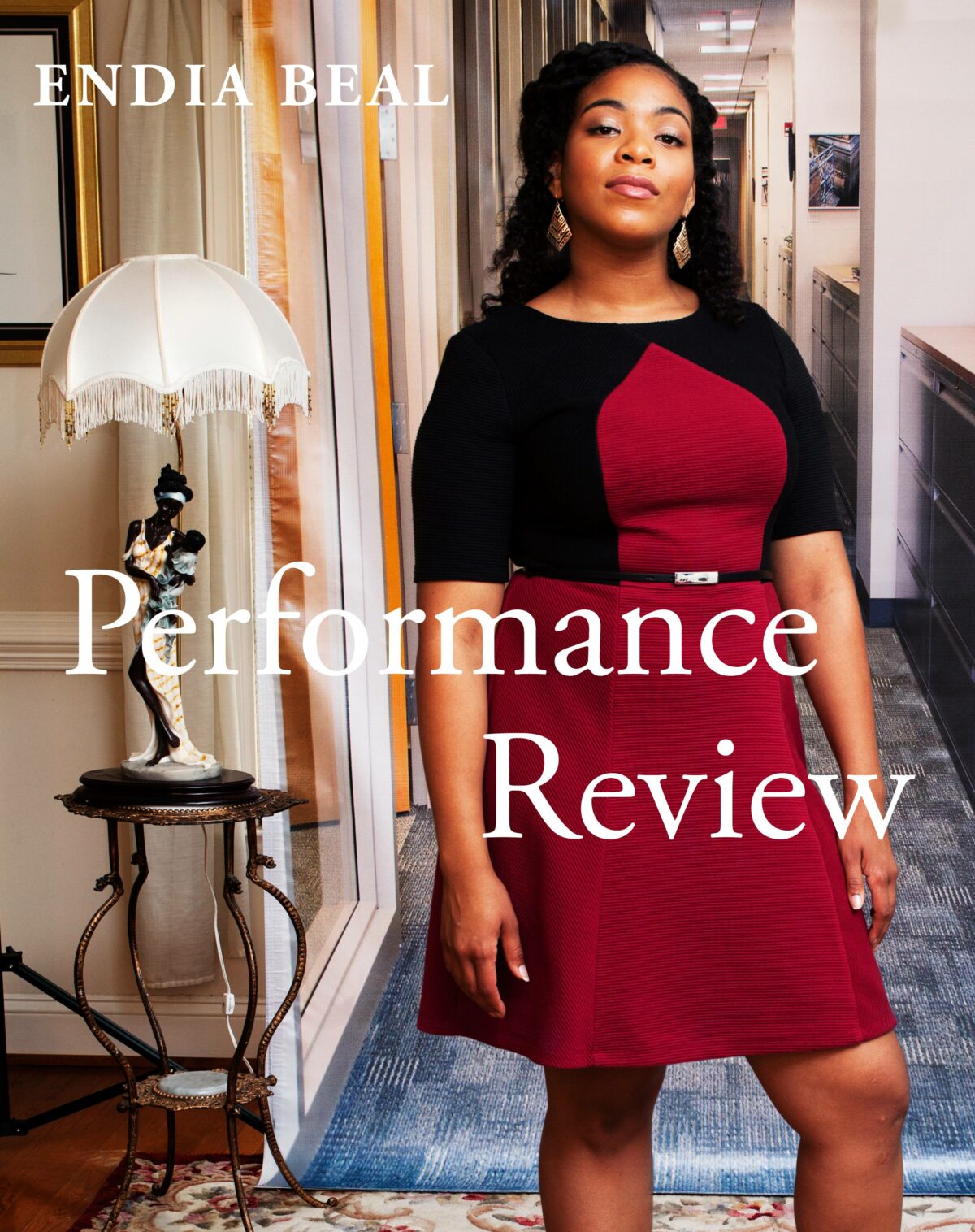

Born and raised in Lebanon and a resident (and citizen) of the United States, Rania Matar could qualify as the August Sander of female portraiture. Her expanding body of work, in both Western and Arab worlds, provides a revealing overview of what it is like to be a woman now, from preadolescence to maturity. A selection from several important series: L’Enfant-Femme, A Girl and Her Room, Becoming and Unspoken Conversations is on view at the Amon Carter Museum in Fort Worth, Texas (through June 17), under the broad title In Her Image: Photographs by Rania Matar, and her work is included in a group exhibition, Féminités Plurielles, at Galerie Tanit in Beirut through April 5.

Lyle Rexer: There are many photographers who have made young women their focus, but you have pursued it to the exclusion of nearly all other subjects. I would be interested to know how you became a photographer and found your subject.

Rania Matar: Someone said to me not long ago, where are the men in your pictures? It took me aback. I mean, I have two daughters and two sons, but somehow I was instinctively drawn to photographing girls and women. It has a lot to do with how I began photographing in the first place. I was awaiting the birth of my fourth child and I realized I wanted to take better pictures of my children. I had done art in college and was trained as an architect, but I had not studied photography. I wanted to capture more of the intimacy of motherhood, the beauty of the mundane moments of what was happening. Then September 11 happened, and it seemed that the world had become divided into Them/Us. As a Lebanese American, I wanted to tell a different story of the Middle East. This is probably the point where I completely fell in love with telling a story through photography, and I never went back to architecture. The other event that was important had to do with my visit to a Palestinian refugee camp in Lebanon in 2002. The conditions were terrible, and yet the camp was so close to the cosmopolitan Beirut in which I grew up. I quickly realized that I connected to the women through our being women and mothers. I recognized our shared humanity.

LR: Your projects combine women from the Arab world and those from the United states. Given the climate of hostility toward immigrants, the denigrating remarks by our president toward women, and the tremendous outrage sparked by #metoo, do you see your work playing a political role?

RM: There is no question my work has relevance in the current context. But its origin is intuitive, and I would say introspective, rather than social or political. It certainly involves my cultural identity but also something more particular to my experience as a woman. My mother died when I was three. I grew up with my father, and so my photographing young women has to do with a deeper exploration of womanhood and motherhood, I think. What is it like to have a mother? What is it like to be a mother? In a way, I photograph all my subjects as if they were my daughters.

LR: I really see your curiosity in the series A Girl and Her Room. When my daughters were growing up I rarely went into their room. I didn’t feel right about it. These photographs give me glimpses that I feel I never quite had.

RM: That series started as I became fascinated by my own daughter when she was 15 – at her transformation but also at the world she created in her space. I started photographing her with her friends and realized how much they were performing for each other and that I hardly recognized my own daughter. I decided to start photographing each young woman in the personal space she was curating for herself, where she was exploring her own sense of identity. At some point I realized that I was exactly like those girls 25 years earlier, in a different country and a different culture, so I decided to include young women in both cultures. As girls, then young women, and finally adults, we all go through the same transformation and encounter the same complexities. My photographs focus on the commonalities of experience as much as they do the diversity.

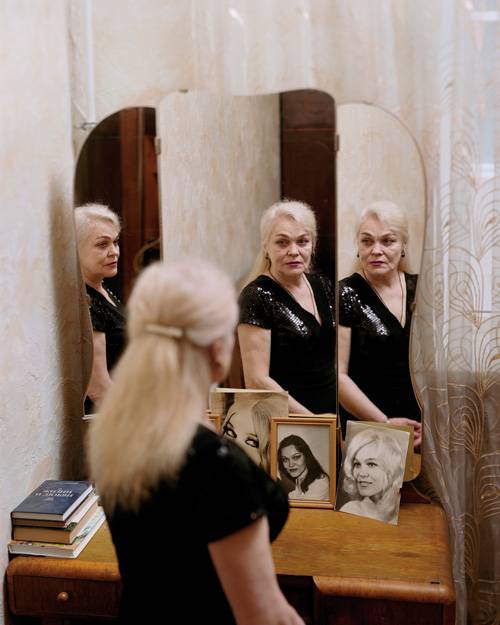

LR: The other series that fascinates me is Unspoken Conversations, which involves dual portraits of mothers and daughters. These strike me as very self-conscious in a good way. Many of the photographs involve mirrors and other reflective situations that offer us some surprising perspectives on the subjects, not to mention their relationships. Did you collaborate actively with your subjects to stage the portraits?

RM: Yes and no. Yes, the work is very collaborative, and no, it is not what I would call “staged.” I might give some direction but I never come to a shoot with a preconception of what I am looking for. This project started when my older daughter left for college, and I realized that as she was growing up, I was getting older, but also that my role as a mother was about to change. I started observing mothers and daughters in the same age bracket all around me. Like the rest of my work, I am exploring through my photography what I find myself and my daughters going through. Observing mothers and daughters together seemed to me to offer versions of the same person separated by the years, and I wanted to explore that. When I am involved in a project like this, it tends to be the only thing I can see. During a shoot, I work with what I find in the setting, yet it always turns into an intimate collaboration. What I am after are the subtleties of the relationship, and I can’t force those. I have to be able to see them. I sometimes glimpse them when we are not shooting and I’ll say, “That’s it, hold that.”

LR: In that regard, the series makes me intensely aware of the different ways younger and older women carry themselves in front of the camera, their different senses of being looked at. Indeed, that is a theme in so many of your photographs, the notion of body language and relation to the camera’s gaze.

RM: In general I found the mothers more self-conscious about being photographed because of the comparisons that they might be making between themselves and their daughters, a version of their younger selves. I give them a lot of credit for agreeing to be part of this project. I observe the subtleties in body language. This is especially true in my series L’Enfant-Femme. With those girls, you can see in their body language how their sense of self is starting to change as their bodies are transforming. In some cases, they become very self-assured and comfortable in front of the camera, in other cases painfully aware. Often they are both at the same time. Another aspect of this, both for the daughters and the girls in L’Enfant-Femme is that they are all raised on selfies, so they are used to being photographed – but a certain way. But here I am shooting medium-format film (they often don’t even know what film is) and they cannot see the back of the camera, so they take the session more seriously. I also ask them not to give me the “selfie” smile, so they have to think about how to pose. There is an awkwardness that also yields beautiful moments.

LR: I think about the many women who have given us great portraits of female adolescence and domestic intimacy – Sally Mann, Judith Joy Ross, Andrea Modica, Rineke Dijkstra, and Elinor Carucci, Do you see yourself as part of this great tradition?

RM: It’s an honor to be mentioned among these photographers. I look at their work and much else, and of course at August Sander’s, but I don’t know myself where I will fit in that history. When I am working, it is entirely personal. It’s a gift to be able to observe life while it is unfolding and make something of it at the same time.