In darkroom parlance, John O’Reilly doesn’t play it straight. The art-therapist-turned-collagist has made a career cutting and pasting photographs to create new images that tell very different stories from their original sources. Now in his 80s, O’Reilly is a member of an American pantheon of alternative photographic pioneers that includes Duane Michals, Jerry Uelsmann, Betty Hahn, and Bea Nettles. The Worcester Art Museum has mounted the first retrospective of O’Reilly’s photo collages, on view through August 13: A Studio Odyssey covers his remarkable career of 50 years, and its title captures his creation of self-contained worlds that open onto the larger one we inhabit.

Lyle Rexer: Several years ago, I had a conversation with a dealer who said that the one thing he would not look at, because it was a refuge for non-photographers with little discipline, was photo collage. I’m wondering whether you encountered resistance to your work because it wasn’t straight photography – and on top of it all, you used Polaroids as source imagery.

John O’Reilly: Not really, although there were always purists around saying “a photo is a photo and that’s the end of it.” There were rebellions against what they condoned, but they were small. I use photography as a medium, and it’s interesting now to see how many artists are playing with photos, altering them. It’s really a new age of digital collage, and I imagine we are not hearing so much about a photo being just a photo.

LR: With collage, process can be very important. It helps us as viewers to know where the material is coming from and how you work with it, especially if we want to tease out some of its latent meanings.

JO: I’ll get an idea, something I like, say, a picture I might have taken or a poem, and I’ll build around it. I take lots of pictures, and I save them, and I gather them from various sources. Lately I’ve even been going to children’s coloring books. Anyway, I pick an image that relates to what I’m thinking about, and I begin to add to it, pushing things around, trying out shapes. I’m really looking for a feeling, something I don’t understand. Sometimes the result is just trash, but other times it will be like a light goes on. The photos accrete, and the visual ideas can get more complex.

LR: It all sounds very visual, very unconscious, and yet much of your work refers directly to writers and the written word. Is your approach, then, also perhaps a bit more calculated or conscious than you let on?

JO: Not exactly, but writing is very important to me. The show is really based on the influence of three writers, Jean Genet, Henry James, and the poet Constantine Cavafy. Genet gives me the permission to be angry; James, well, I read James whenever I get depressed; and Cavafy tells me there is no time. It’s one of the reasons why I portray myself in the nude in many of the collages. I want to strip myself of anything that will locate me in time.

LR: There are also references to Gerard Manley Hopkins and Hart Crane, whom a school friend of mine once referred to as “one of those damned difficult poets.”

JO: Hopkins’s struggle was that he lived a life of desire but forced himself to turn his back on it. He saw this beauty but could never bring himself to touch it. Crane, whom Marsden Hartley memorialized in his painting, was so confused about his desires that he eventually wound up jumping off a boat and drowning.

LR: These names, with their anguish about sexual identity, suggest a strong element of autobiography in your work.

JO: I lived a closeted life. I grew up in New Jersey and was never in the gay world. As a kid you know all about sexuality, and you know nothing. I hid from it. I once broke off a friendship just because someone showed me an erotic cartoon book of Blondie and Dagwood. But I knew I was different, and I sometimes felt I was nothing. In high school I never kissed the girls goodnight after dates. Later when I was teaching at the University of New Hampshire, I had to deal with people throwing dinner parties to get me married off. But pictures became a key to coming to terms with my sexuality, to trying to find out what and who I am. They began as a psychotherapeutic examination. There are lots of disturbances in my work.

LR: I especially like the simple one based on a cartoon, titled Apparition (2014), in which a young boy with glasses sees the half-torn image of a male body.

JO: You’ll notice that one lens of his glasses is blank. Seeing and not seeing. I probably had a dream like that. My work often plays between childhood and adulthood. As a child, I felt like a grownup, and as a grownup, I want to be more childlike.

LR: As I mentioned, that’s an especially simple and coherent image. It strikes me that there are really two ways of dealing visually with collage. One is to unify elements into a single form or tableau that can be read. The other is more open-ended, to treat the frame as a space of relationships. These imply very different goals. I see both in your work.

JO: It represents more of an evolution. When I began making collages, I intended my first ones to look like photographs. I made only straight edges, and I wanted the end result to be a single image. But over time, I felt a need to be less controlled and work unconsciously. I placed objects on my tabletop and photographed them, and thought more about the work as a construction, or a kind of theater. I am creating a space I want people to enter. De Chirico is an inspiration, and his image shows up in my work.

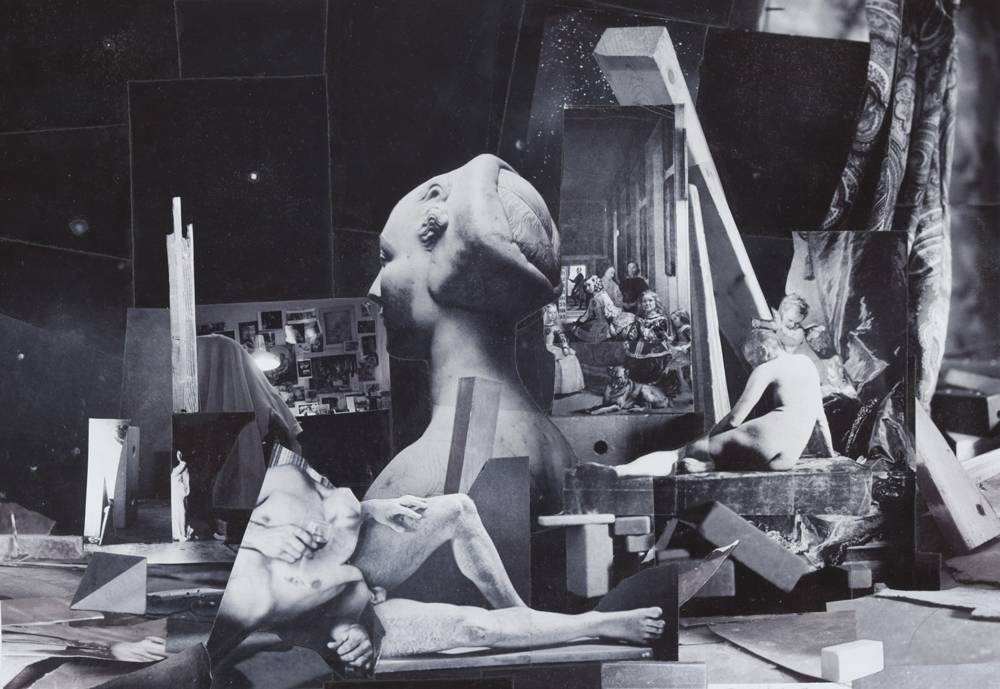

LR: That complicated sense of space is completely engrossing in Eakins Posing (2006). Everything shows up there and resonates: Thomas Eakins’s own photographic nude studies, tabletop blocks, pieces of lumber, a bust, and a snippet from Las Meninas (1656), the famous painting of Velázquez that is itself a study in visual complication.

JO: I hope people get some of the connections. Eakins loved the paintings by Velázquez, and so do I. I first saw them when I lived in Europe in the 1950s. Eakins himself was eccentric and spent a lot of time naked in his own house. I identified with him, he was so off-balance. The painting of the Spanish royal family opens up a lot of other associations, about their early deaths, about King Philip IV becoming a hermit in the Escorial and with the help of a nun attempting to channel communication with his dead son. It reminds me of my family.

LR: That’s dizzying.

JO: The connections aren’t calculated. They expand as I go along.