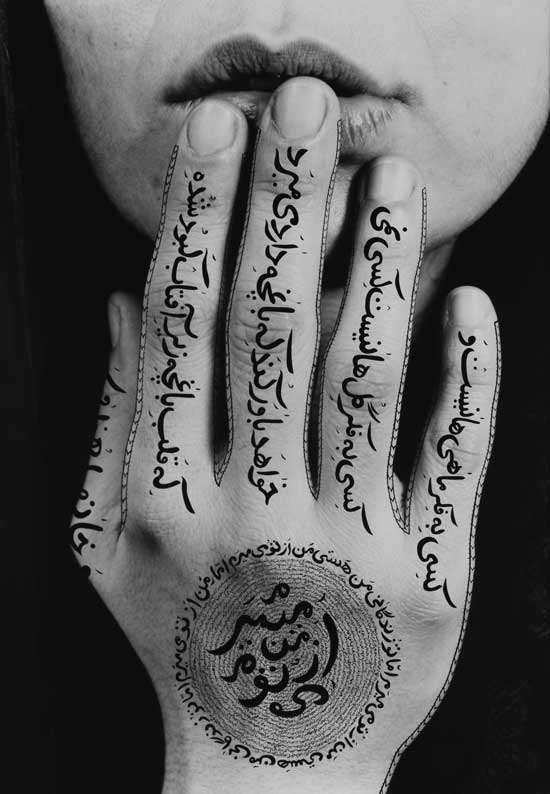

Photographer and filmmaker Shirin Neshat is among the best known international artists. Born in Iran and educated in the United States, she has helped open doors into the art world for work dealing with Islamic themes. Her current retrospective exhibition, Shirin Neshat: Facing History, is on view at the Smithsonian’s Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden through September 20.

Lyle Rexer: I was thinking about your work when I saw the recent retrospective at the Guggenheim of Monir Farmanfarmaian. As an artist she struggled to integrate her internationalism with her identity as an Iranian, and her vision of modernity with Iranian society’s ambivalent relationship to development. Do those themes resonate with you?

Shirin Neshat: Because we are from different generations our experiences are very different. Her roots as an artist were in Iran, and it was to Iran she always longed to return, and she blossomed when she finally did. I was disconnected from Iran, and all my experiences as an artist happened in the U.S., so I have never felt the same kind of longing. My hybrid identity is not deeply rooted. I am always accompanied by a shadow of myself. If I lived in Iran, I would probably stop being an artist.

LR: So you need that distance?

SN: It is who I am. For me the question is always, does the work have integrity? Is it true to my experience and what I want to communicate? I look at many younger artists and ask that question, because it seems that they sense that in order to succeed as artists, they must focus on Iran, in the narrowest of ways. For a long time I had no interest in Iran. And the projects I am working on now don’t deal with Iran at all.

LR: I am curious to know how your work is regarded in Iran. Have you been back recently?

SN: I have not been back since 1996, and I have to say that I have a mixed audience with very mixed responses. I am respected there, but some people question my political views, some think I am making art as an outsider. Yet my presence is more complicated. My film (Women Without Men) has been shown underground, and I have been very outspoken, so I am probably better known as a public figure, rather than just as an artist. But that has pitfalls. It is wrong for me to use a public platform too often. I speak with the voice of an artist, not a political activist. When I was asked to talk at the World Economic Forum in Davos, for example, that was the position I took.

LR: The Green Revolution inspired your remarkable portrait series The Book of Kings. Given the pitfalls of being a public intellectual, as you say, can you talk about your involvement in that period?

SN: The experience was euphoric and unforgettable. I had never been politically active, but this was all about a country and a community. Many of us felt that the Arab Spring grew out of the Green Movement, and we followed the subsequent developments in Egypt and Tunisia as closely as we followed our own, and we went to their demonstrations in New York. I became close to people from all over the Arab world at that time, and a number of them became subjects for my portraits in the series. I wanted to pay homage in this project to the inspiration I felt.