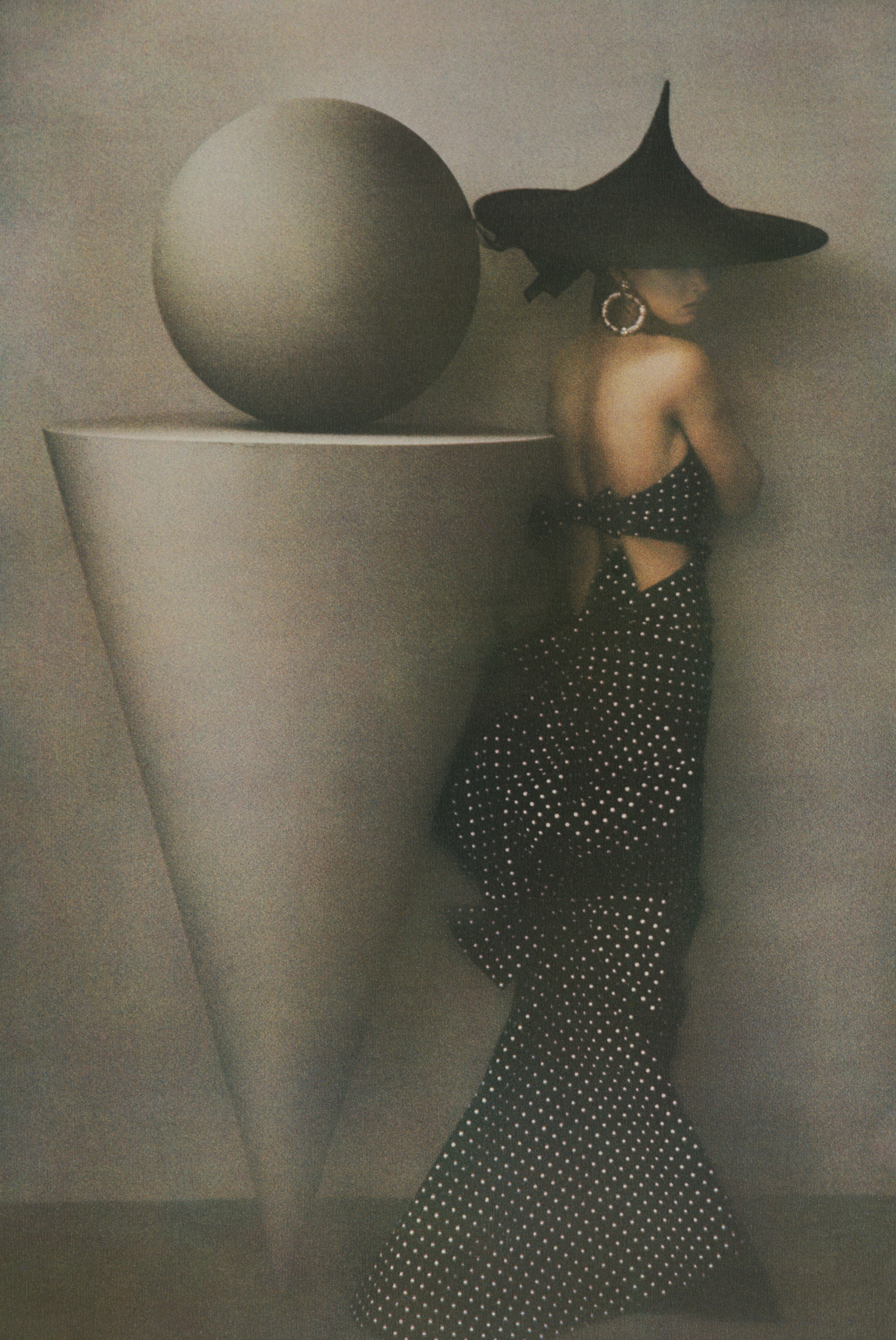

The photographs of Flor Garduño create a bridge between worlds – the sacred and the quotidian, the body and the spirit – allowing us glimpses, in the words of Mexican novelist Carlos Fuentes, of “a moving portrait of eternity.” Her early apprenticeship with Manuel Álvarez Bravo provided a model for imaging historical realities through a language of symbols. A mini-retrospective of her black-and-white photographs is on view at Throckmorton Fine Art through February 25.

Lyle Rexer: The exhibition of your work in New York is especially timely for several reasons: first because of the image of Mexico that is promoted by the press and certain politicians in the United States, and more broadly, because of the climate of fear and suspicion that poisons relations with those considered “other.” So my first question is, how do you as a Mexican artist respond to the climate that is being created? Do you see your work as a force against that?

Flor Garduño: [shaking her head in a gesture of disgust and disbelief]. I can hardly consider it. We have elected, in my opinion, a fascist for the next four years. I think of my photographs as a form of resistance.

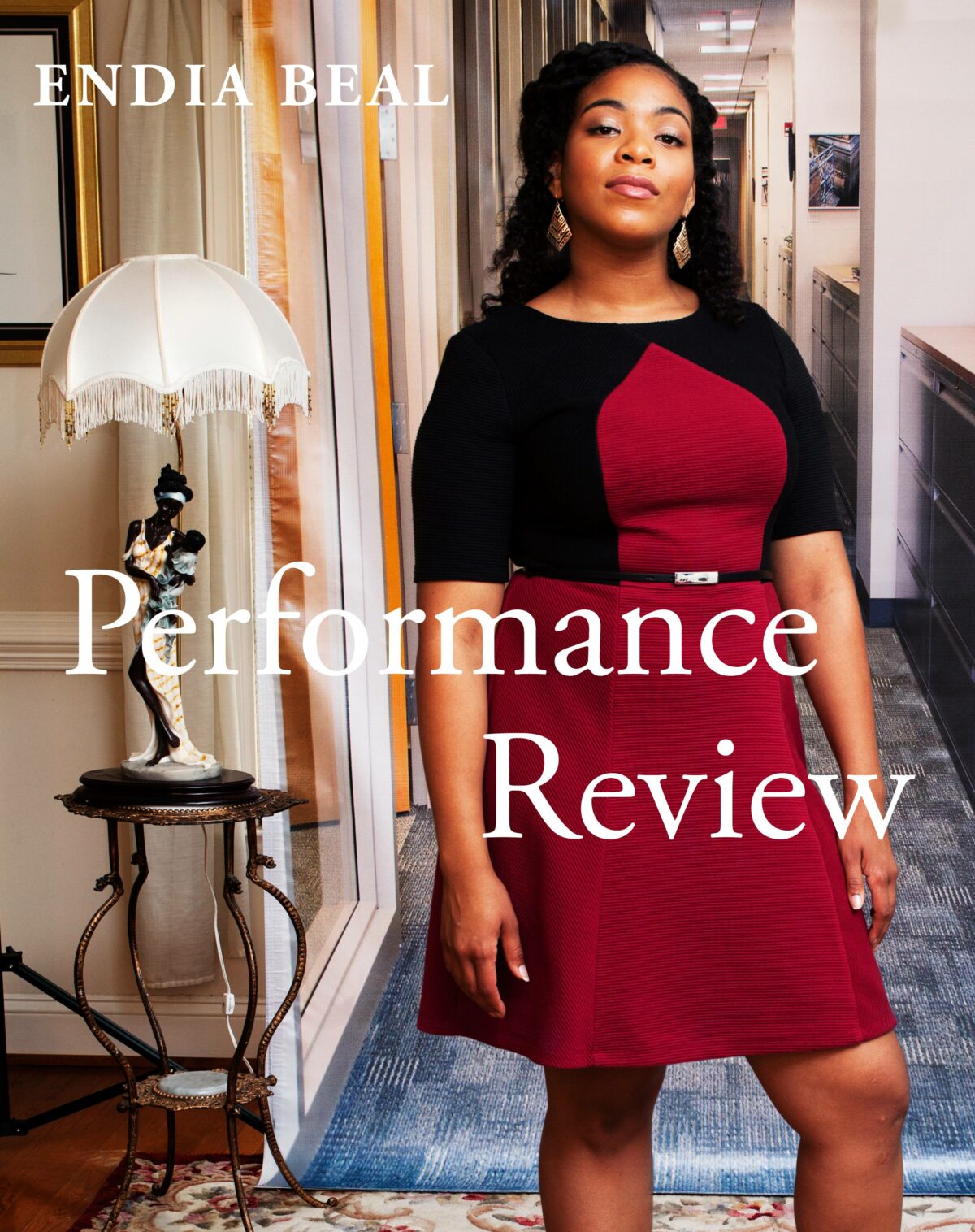

LR: In a similar vein, many of the images in the exhibition at Throckmorton emphasize the importance of women and the female body – an importance that is both social and mythic. Given what has happened in Mexico over the last decade and with the results of the U.S. election, do you see your work as playing an especially valuable role in women’s struggles?

FG: I would say the ordinary and the historic, or symbolic – these two realms intersect in my photographs, which are a celebration of fertility, in the broadest sense. They are dramatic, for sure, because it seems to me we are in a period of aggression against women, around the world, and certainly in this hemisphere. It is systematic, coming from governments, politicians, cultural leaders. It is the fruit of economic and social frustration. And in Mexico, with the murders and rapes, the aggression has become almost a norm. As a woman of the middle class, I also know that we suffer inside our families, that patriarchy is ingrained. But the humiliation is most terrible with poor women. One woman I met while photographing spent her day from dawn to dusk picking through heaps of trash, looking for whatever she might sell to support herself and her four children. I want to express our dignity, beauty, suffering, and resistance. This is the force of our gender.

LR: Yes, the symbols of fertility are everywhere, but I see the photos as celebrating the beauty of women in ways I can’t imagine a male photographer ever attempting.

FG: There are great photo documentarians, great fashion photographers, all types of

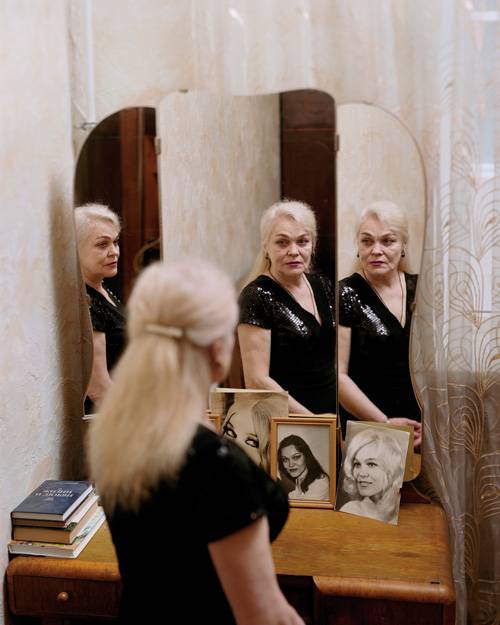

photographers, but I have an independent interest in beauty, whether in my nudes, still lifes, whatever I photograph. I strongly believe that beauty is curative. It’s physical. I’ll tell you a story: I was driving in Switzerland, where I had an exhibition, and I heard on the radio a discussion with a psychologist who helped cancer patients. One of her patients who visited regularly would always sit so she could look at a poster on the wall of a young girl with a basket of flowers on her head. She said, “It changes me. I feel better. It gives me strength for the fight.” I realized she was talking about the poster from my exhibition! It gave me incredible satisfaction to hear about the power of beauty.

LR: That photo [Canasta de Luz/ Basket of Light, 1989] is wonderful for its simplicity. It’s anchored in a moment but it leaves that moment behind for an experience beyond time.

FG: There’s another story with this picture. I had been photographing with my then-husband in Guatemala. I had been working all day when I suddenly saw this young girl. I couldn’t speak the language but my husband asked her to stop so I could take her picture. I need to have a relationship with the people I photograph, but she just smiled and kept walking. I hustled along with her for two kilometers trying to figure out how I was going to take her picture until she finally reached the door of a house. I asked her if I could come inside with her, and she said, of course. It turns out that in that region the various saints are venerated in rotating locations, each year a different house. Holy images are displayed, along with offerings of fruit and flowers. I had come to the house of the Santo Niño, and inside, in an open patio, the young girl with her flowers caught the last light of day, and I took my final photograph. Normally I would have taken a photograph when I first saw her, and that would have been it. To this day I still wonder what it was that made me follow her and keep going until that last moment.

LR: And I wonder what it was that made her refuse to stop, so that you would have to follow her all the way. Did she know something? A wonderful story. You need to write it down.

FG: There are stories for every one of these photographs. But, I’m not a writer.

LR: Write them anyway. Just do it. One final question. As I look at the exhibition, it seems to me that your recent work has become simpler, almost minimal, even more symbolic. What’s changed?

FG: I don’t know that anything has changed except that I am more content, more tranquil. I used to suffer so much over my work. I worried about my creativity and obsessed about the quality of everything I did. My biggest enemy was myself. Now I just work. I do photography with joy.

LR: I’m not surprised about your obsession with quality. In a digital age, it is a deep pleasure to see these black-and-white prints, so rich and evocative. Something also true of many of your books. Witnesses of Time, for example, really manages to do justice to the photos. You must be a nightmare for publishers.

FG: [Laughs] For publishers, yes, but not for printers. Book production is beastly. You have to control everything if you want to translate the images you have made and the experiences they offer into a book. And it costs money to get the best quality. But I understand printers, and I appreciate them. I know what they are capable of, and they respect me. It’s a true collaboration.