Sara Cwynar’s studio is on the third floor of an artist-filled walkup in Brooklyn’s Gowanus neighborhood. It’s a small space that’s relatively clean and organized, which is a mild surprise given that Cwynar’s pictures often seem like the work of a hoarder.

As she sits down to talk about Gilded Age, on view at the Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum in Ridgefield, CT, through November 10, a big printer nearby lets out a sigh, as if from exhaustion. It makes sense – the artist does a lot of printing, often for an individual piece. Consider, for instance, the recent triptych 141 Pictures of Sophie 1, 2 and 3, 2019. Cwynar took a straightforward photograph of a ubiquitous e-commerce model, printed it out, then layered hundreds of internet-sourced images of that same model on top of it.

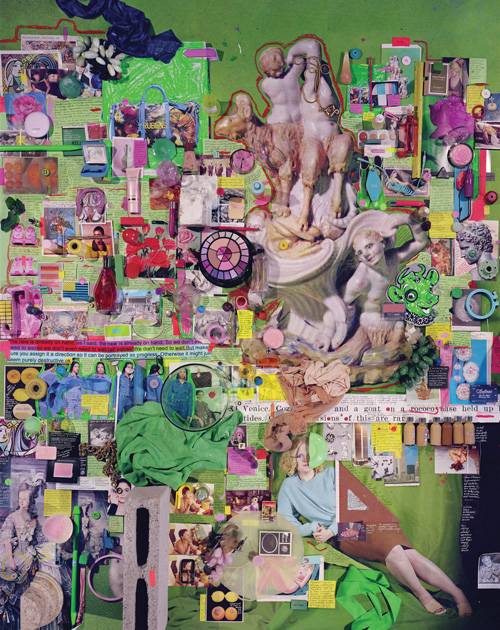

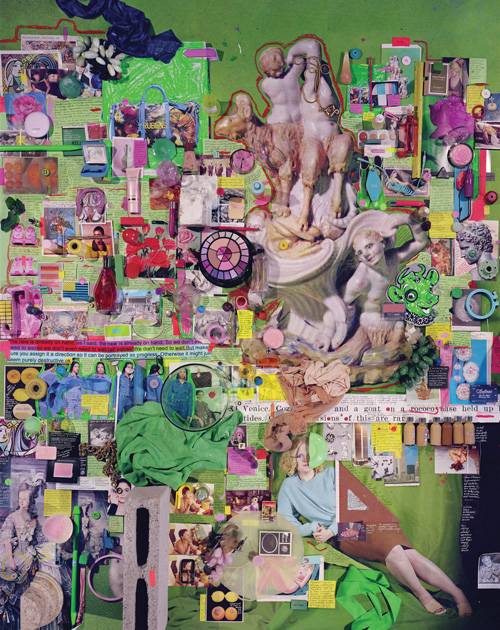

This is emblematic of how Cwynar’s photos tend to go: she shoots an image, prints it, then arranges objects on top of the print and re-photographs the composition. Sometimes a single picture is composed of dozens of prints stacked atop one another. Other times it will look like someone laid out the contents of a long-forgotten flea-market bin onto a fashion shoot outtake. It’s a visual language that’s unmistakably her own: eBay bric-a-brac mingles with cheap art postcards and found family photos. Every aspect of the final product – the perspectival trickery, the distorted scale, the attention drawn to the photographic print as object – is a reminder of photography’s artifice.

“One of the great problems that I’m always trying to sort out is how to make what is essentially a pile of garbage look like it’s not a pile of garbage,” says Cwynar, with a self-deprecating smile. “I’ll spend days moving things around to try to get it to be something that has that holistic logic to it. The way photography transforms things is at the core of my work. I find that layer of removal from what the object actually is to be endlessly exciting and satisfying to look at. It allows for combinations of things that wouldn’t otherwise be possible.”

Like her printer, Cwynar is tired. Having just returned from a monthlong residency in Italy, she’s battling jetlag. This year alone, the 34-year-old artist has mounted four solo shows in three different countries, two at major museums. (In addition to the Aldrich exhibition, she opened a show at the Milwaukee Art Museum in March). She’s also producing a video series for MoMA and has her first monograph coming out with Aperture next year. But that grind is normal for the artist who has, in the nine years since first picking up a proper camera, received her MFA at Yale, been the subject of several institutional exhibitions, and had her work placed in the collections of more than a dozen museums.

It began when she was fresh out of undergrad at York University in Toronto. She began working as a designer for the New York Times – an experience that helped put into focus some of the larger ideas she had been thinking about, she explains. “It was really fascinating to watch, from inside this big institution, conversations play out about what an image means or how we can visualize something, then put it out into the world and see how differently people would actually react to it.”

Even today, the roots of this idea still inform Cwynar’s work. Take her minimal pictures of flowers, her essayistic films on the beauty industry, or her everything-but-the-kitchen-sink assemblages: with her eye for design and pop-anthropological interest in consumer objects, Cwynar toes the line between critiquing the capitalistic fetishization of things, and enacting that desire herself. “I’ve always wanted to be on the line,” she explains. “I don’t always know if I fall on the right side of it, but that’s interesting to me.”