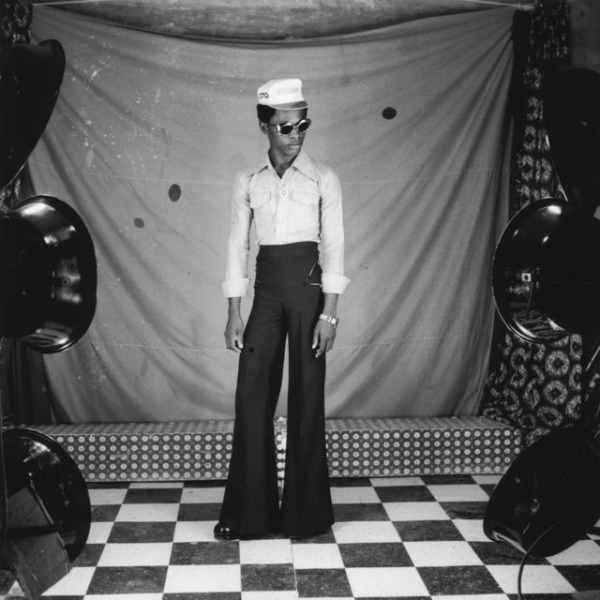

Specimen Study (#6)

Caitlin Teal Price is a native of Washington, D.C., a city defined in part by its increasingly transient population. In the past few years, Washington has strived to rebrand itself as a hub of cultural and not merely political activity. A burgeoning art scene is host to a number of contemporary galleries and a small but dedicated group of artists, Price among them.

After studying photography at Parson’s in New York City, Price earned her MFA from Yale in 2009. She spent the following year traveling the country, adding to the portfolio of images in her series Annabelle, Annabelle, which she began as her graduate thesis. This body of work, a series of staged portraits of middle-aged women, won her recognition as a photographer of exceptional talent. Price has since exhibited this work at the RISD Museum, the Corcoran Gallery of Art, and the National Portrait Gallery. Most recently, Price has been granted access to the Smithsonian Institution’s archives and has been working with their collection of taxidermied birds and ornithological ephemera.

Price first began photographing preserved avian specimens while pursuing her graduate degree. Her early paired images Pretty Bird and Wrapped Birdie were shot on location in New Haven’s Peabody Museum of Natural History. Her work with the Smithsonian collection represents a broader investigation into the human connection with these creatures and the impulse to catalog and preserve them. Price cites her interest in how particular species are anthropomorphized and invested with mystical qualities. The collection itself is also a key factor in the work. The Smithsonian’s Division of Birds houses over half-a-million avian specimens and accounts for nearly 80 percent of the world’s known birds. It bears mentioning that they were never intended for exhibition. Stuffed with straw and often missing eyeballs, their carcasses are frozen in variously awkward displays of rigor mortis. It’s Price’s hope, however, to capture the hints of life in these specimens, some now dead for a century or more. Many of the birds she photographs have been cataloged along with their eggs and preserved nests, and her interest in these relics suggests a link with human funereal traditions of burying the dead with their prized possessions.

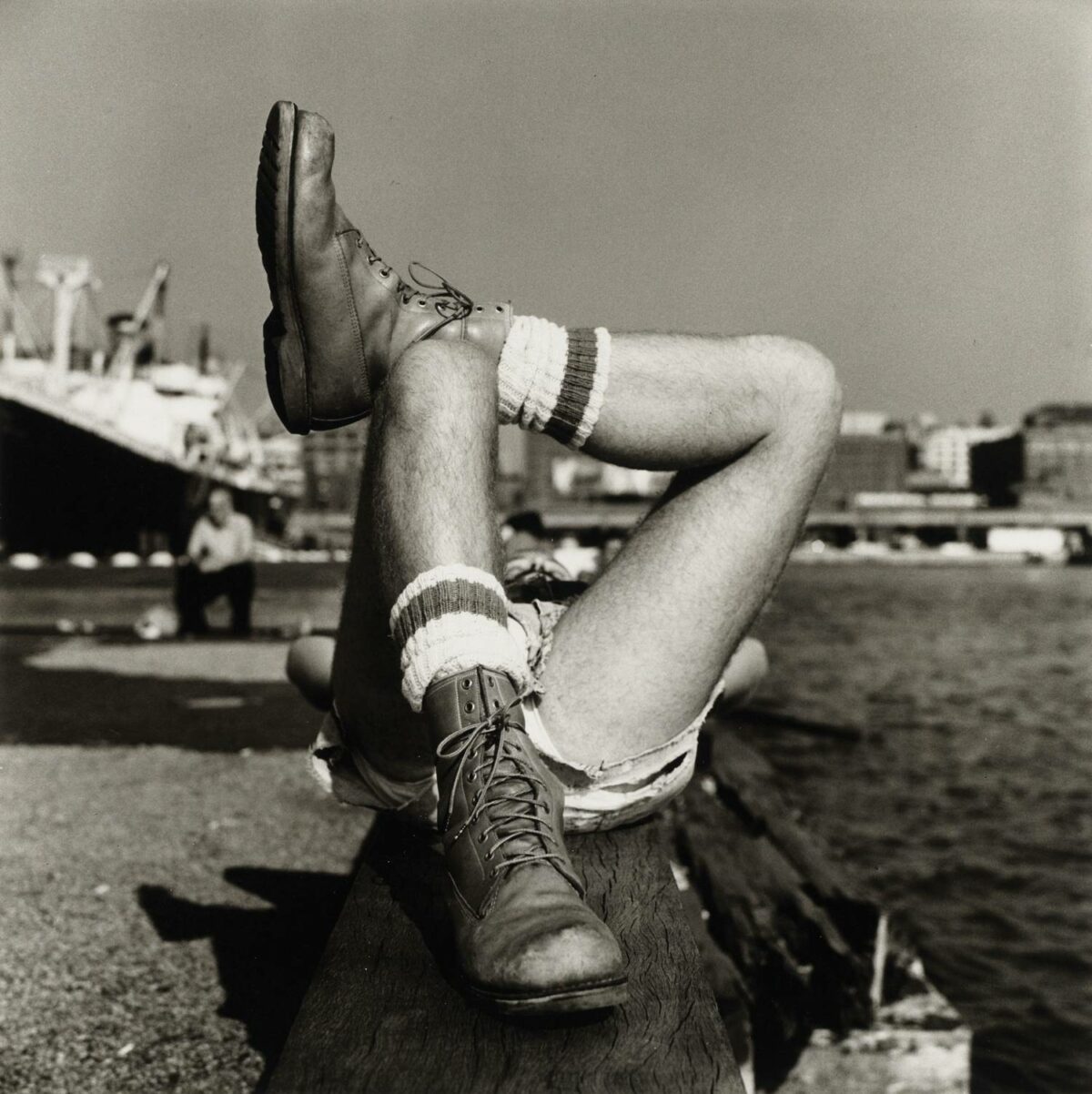

Although her recent work with the Smithsonian marks a departure from a career largely spent making portraits, Price has a clear affinity for taxonomies of the unusual. In her series Washed Up from several years ago, Price demonstrates her facility with the medium’s more voyeuristic modes. These photographs of Coney Island sunbathers present a range of colorful humanity, shot from a uniform perspective directly above them that gives the images a coherent rhythm without feeling contrived. The subject matter is familiar territory, but Price has nimbly picked her own path amid the footsteps of her predecessors. Her portraits catch the bathers in death-like repose, lying prone among their belongings. Seen as a group, Price’s beach-goers are strangely reminiscent of museum specimens, each carefully laid on protective cloth, eyes closed, prominent anatomical features on display. In these series, her talent lies in asking us to accept beauty not only in unlooked for places, but in scenarios that are not always comfortable.

Specimen Study (#45)

The Dancer