The idea behind the In The Studio column is to bring readers into the photographer’s studio to explore the artist’s process, to consider how the work is conceptualized and the means by which it is produced. To look under the hood, so to speak. But artists often find inspiration through partnerships outside of the studio, in unexpected collaborations with institutions or corporate partners, so for this column, we’re peering behind the scenes to see how one such project, Ann Hamilton’s ONEEVERYONE, came about.

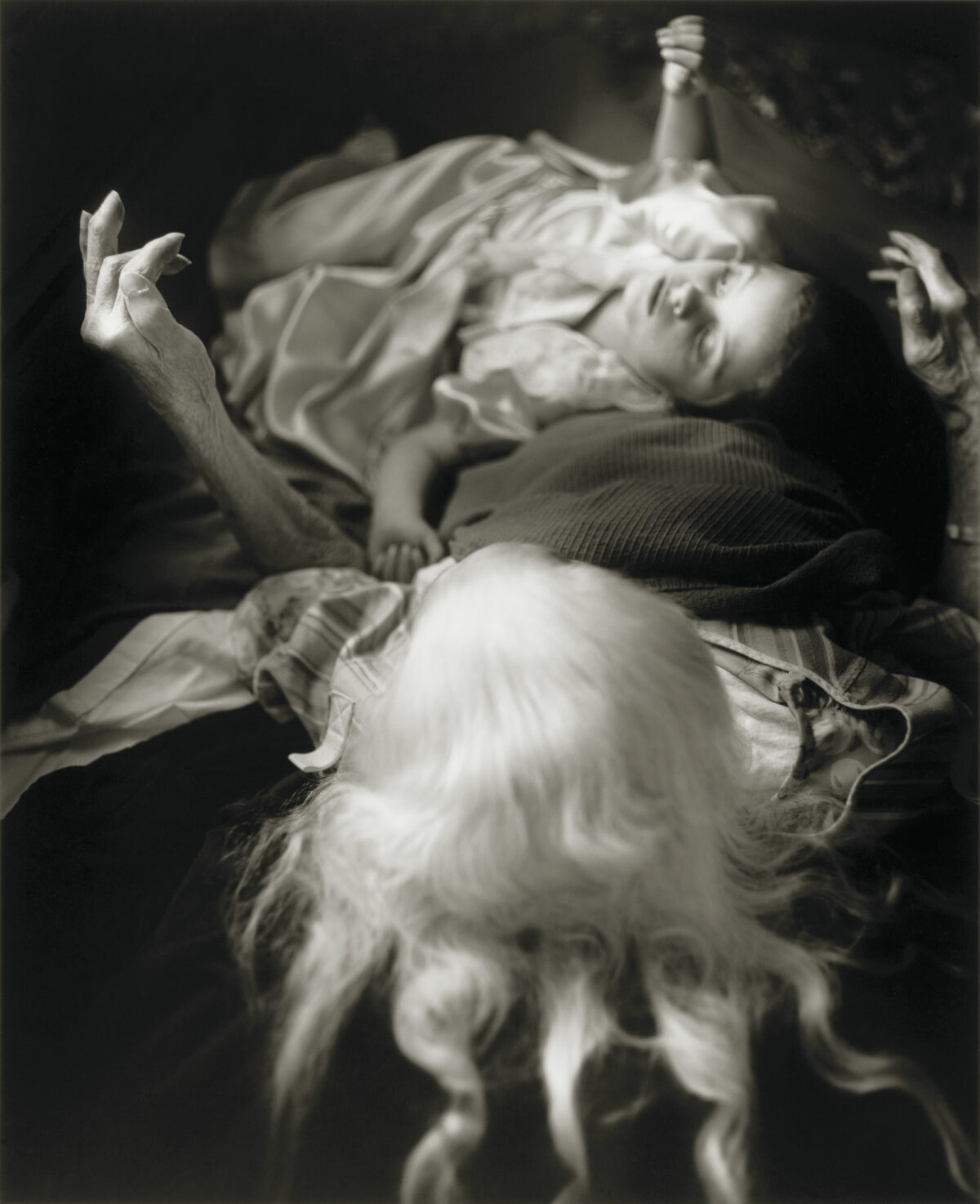

Hamilton is best known for her large-scale multimedia installations, but she has made photo-based works over the years (including her 2001 project, face to face, in which she placed a small pinhole camera in her mouth and exposed the film by opening her mouth). More recently, she created an expansive photo-based public art project, commissioned by the Dell Medical School at the University of Texas at Austin. The seed for the project was planted in 2012, when Hamilton participated in a program called Factory Direct: Pittsburgh, in which the Warhol Museum connected artists with Pittsburgh-based businesses. Hamilton was partnered with Bayer Material Science (now Covestro), a firm that produces high-tech polymer materials, and a chemist at the company introduced her to a material called Duraflex®, a thermoplastic polyurethane membrane that she describes as feeling like a heavy rubber shower curtain. It had a milky surface, so that everything behind the curtain was out of focus except for what came into direct contact with it. Hamilton photographed employees at Bayer as they stood on the other side of the curtain with objects related to their work (a test tube or a beaker, for instance). Several years later, she photographed visitors the ADAA Art Show in New York in the same way.

She returned to this process more recently, when the University of Texas at Austin’s public art program, Landmarks, commissioned her to create a public art project for the university’s Dell Medical School. Positioning people behind the Duraflex® curtain, she photographed more than 500 volunteers in the community of Austin, including patients and caregivers of all kinds, from doctors and nurses to family members. Twenty-five of the portraits were printed as life-sized enamel panels that will be permanently installed in the medical center, and a selection of smaller portraits will be on view at the university’s Visual Arts Center from January 27 to February 24.

In describing the process behind these partially opaque portraits, Hamilton notes that the subjects could not see her, but had to follow her voice alone, telling them to turn a bit, or press against the curtain. That exchange, she suggests, led to “an interiority that is more private, more vulnerable than the self we offer up in the world of a constantly present camera.” Her portraits are about the physical characteristics of the material, but also her subjects’ responses to it: The curtain provided a protective shield, from her and from the camera, allowing a certain freedom from self-consciousness. It also allowed them to pay close attention to sound and touch – senses that have been central to her artistic practice but don’t normally fall within the purview of photography. The result: gestural, spectral pictures that redefine the photographic portrait.