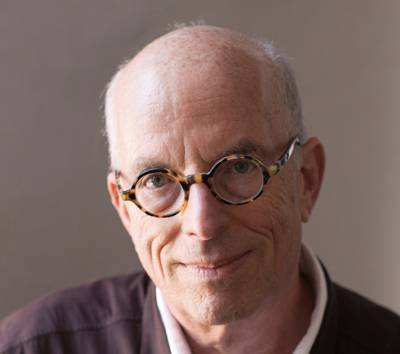

Linda Benedict-Jones, curator of photography at the Carnegie Museum of Art, recalls first seeing Duane Michals’s photographs in the early 1970s: “I thought he was a breath of fresh air,” she says, “I’ve always admired him. And I didn’t even know until I moved to Pittsburgh that he was born and raised here.” Storyteller: The Photographs of Duane Michals, which runs from November 1 through February 16, is the culmination of several years of work by Benedict-Jones. “When I first saw his work in 1971, I had a smile on my face, and so did hundreds of thousands of other people,” she says. “This was the era of the decisive moment, but that never worked for Duane. He always said: ‘I needed the moment before and the moment after.’ His work was completely out of the box.”

Benedict-Jones grew up in Wisconsin and majored in English, but the last class she took before graduating was a photography class. “So of course I fell in love with it,” she says. Her young husband was invited to play professional basketball in Portugal, so for four years she immersed herself in Portuguese and photography. After a few years, the two of them found they way back to the United States, and Benedict-Jones earned a masters degree in visual studies from MIT. Polaroid was MIT’s neighbor, and she was offered a consulting job that eventually turned into a position as curator of the Polaroid collection. “Everything was perfect,” she says. “I couldn’t have written a better script.”

But then her husband, who had given up basketball for academia, was offered a job at Carnegie Mellon University. She was not initially thrilled with the proposal of leaving Boston for Pittsburgh, but she eventually warmed to the idea. Now, she wouldn’t think of leaving. “It’s a beautiful city with incredible diversity in terms of cultural life, performing arts, visual arts, theater, dance,” she says.

Shortly after she moved there, she and a colleague, Charlee Brodsky, proposed a show to the Carnegie Museum called Pittsburgh Revealed: Photographs since 1850. It was a sleeper hit, drawing crowds of viewers. She suggested she become the museum’s photography curator, but the position didn’t exist, and the museum wasn’t ready to create it, so Benedict-Jones became director of the nonprofit Silver Eye Center, a job she kept for 10 years. “It was an 80-hour-a-week job,” she says, “but it was a labor of love.” Just about the time Benedict-Jones was thinking about turning over the reins to someone new, she got a call from Richard Armstrong, the director of the Carnegie at the time, offering her the job she’d wanted ten years earlier.

The collection, when she arrived, had a little bit of this and a little bit of that, not surprising for a museum without a dedicated photography curator. Among its strengths, though: a large selection of W. Eugene Smith’s images from the Pittsburgh Photographic Project, spearheaded by Roy Stryker; and the Teenie Harris Archive, with 80,000 negatives from Pittsburgh’s vibrant African-American community from the 1930s to the 1970s.

“When I moved here the museum paid almost no attention to photography,” says Benedict-Jones, “but then there was Pittsburgh Revealed, then W. Eugene Smith, then Teenie Harris, and now Duane Michals, and the Hillman Photography Initiative. It’s really fantastic.”