Chelsea dealer Miyako Yoshinaga references the movie Lost in Translation, starring Bill Murray, when describing the evolution of her role as a dealer. In today’s global economy, where artists might be born and raised in more than one culture and thrive and show their artwork in others, incredible subtleties are at play. And Yoshinaga, whose bailiwick is contemporary and postwar Japanese photography, is a kind of translator’s translator. “Moriyama, Araki, Sugimoto – I understand their status and people’s fascination with them,” she says over cups of green tea in her sunlit office on West 27th Street, “but there are other artists making fascinating work of equal quality who are not appreciated or shown here. By 2004 I realized that, as a dealer, I would have to specialize if I was to make a difference; and I know that this is where I can do the most good.”

Yoshinaga has a softspoken graceful demeanor that belies a bubbling sense of humor. She grew up in Kumamoto, in southern Japan; her mother was a housewife-turned-educator, her father was a judge. Minamata, site of the tragic mercury poisoning of thousands, was also in the prefecture of Kumamoto, and her father had to rule on the case. The young Yoshinaga grew up with a respect for balance and discernment.

She attended Keio University in Tokyo, majoring in cross-cultural psychology and researching shamanism on the Okinawan Islands. After graduation, she worked at a local publishing company, saving money for trips abroad, where she immersed herself in major museums. After five years she took what was supposed to be a year’s leave to pursue museum studies at NYU. But she never left New York. A three-month internship at the Brooklyn Museum turned into a part-time job as research assistant in the Asian art department. A colleague from Taiwan with DIY-dealer aspirations called her to arms one day: “We have to show people Asian art is alive, not dead!”

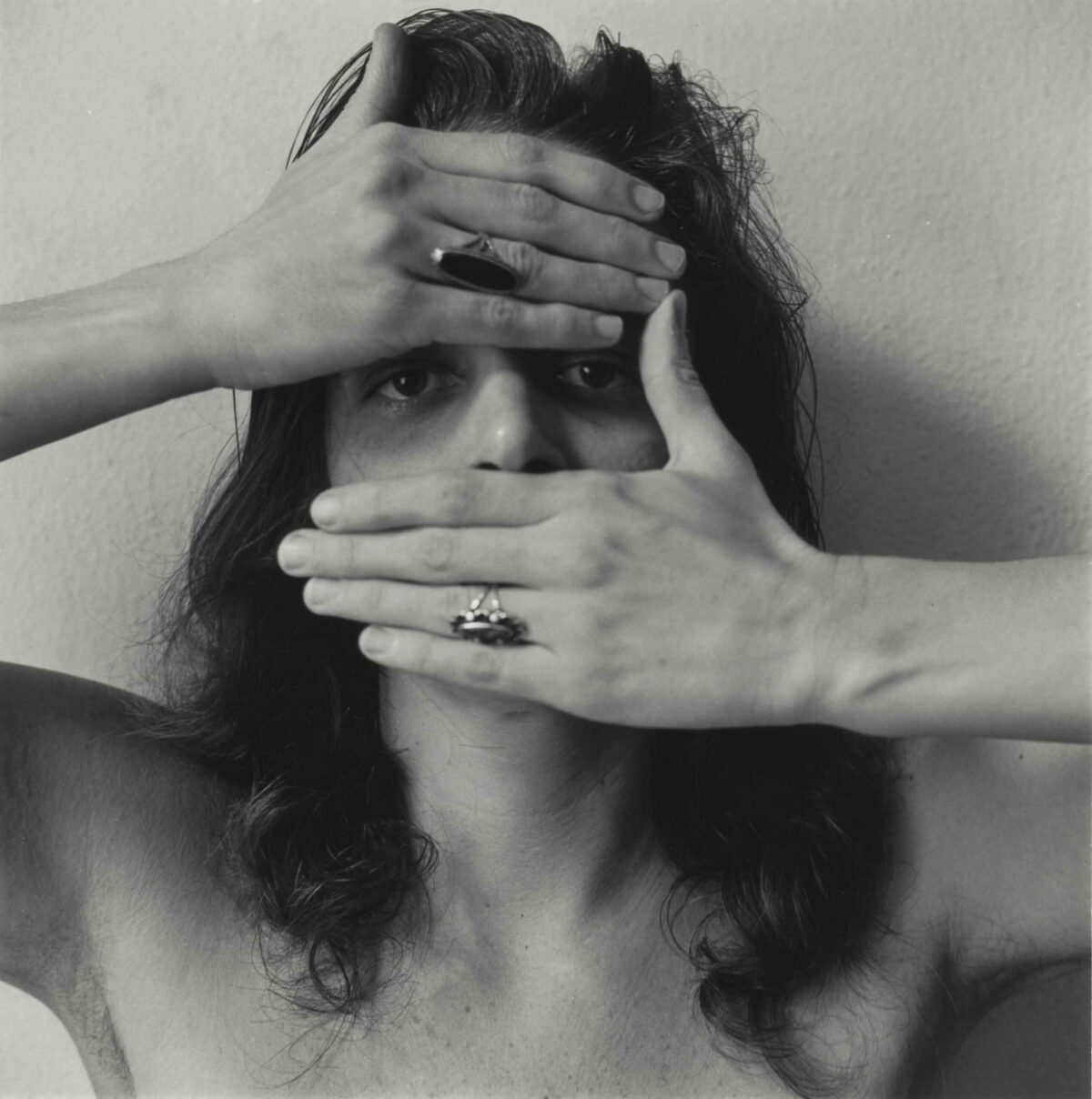

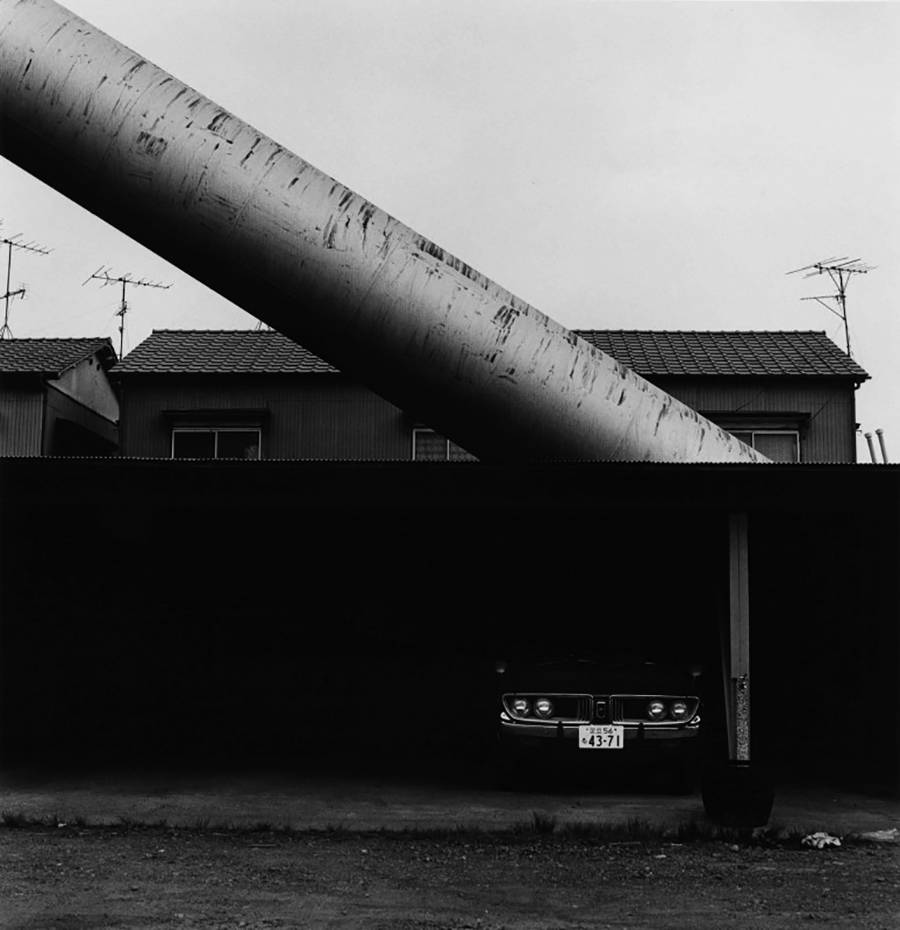

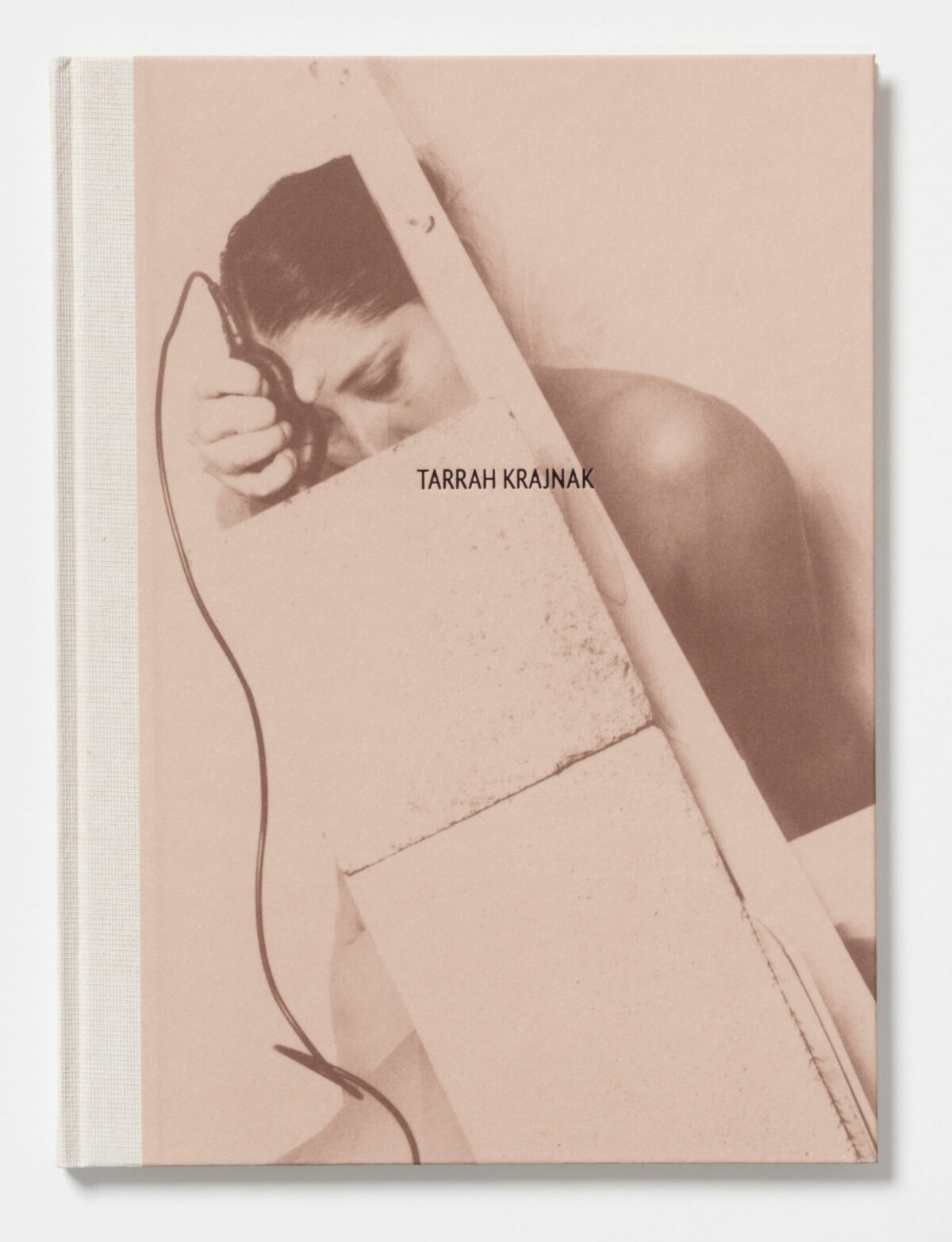

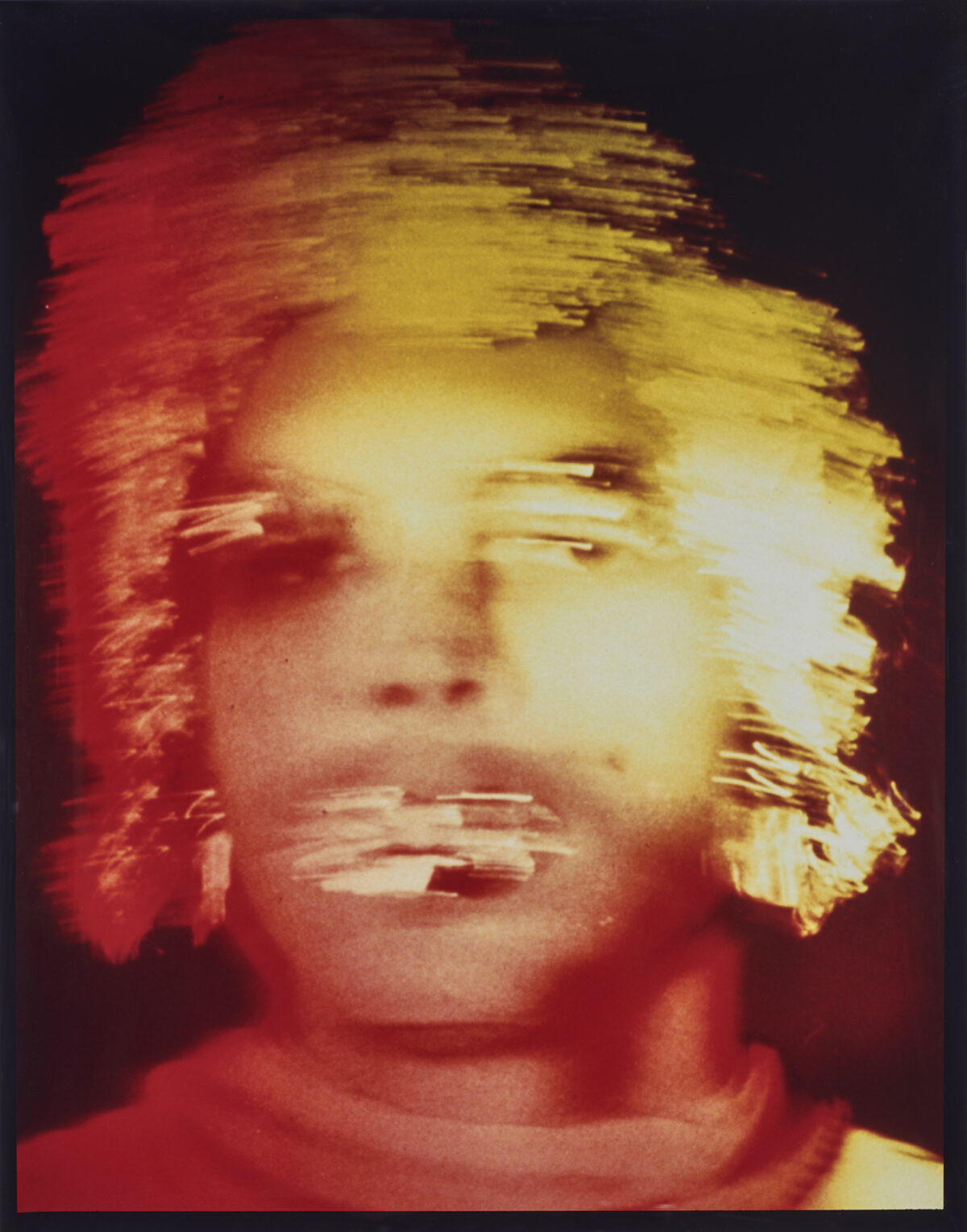

Over the next two years, the two of them put on pop-up shows of under-recognized artists. When her partner decamped back to Taiwan, Yoshinaga, who had been building a collector base, took the plunge into private dealing under the moniker M.Y. Art Prospects. In 1999, she went public in a space on West 29th Street, and in 2003, she moved into her current digs. Although she shows work in a diversity of mediums, 70 percent of her exhibitions are photography. Difficult-but-worthy fare gets the museum-quality treatment in her well-lit, single-room space – black-and-white vintage work by Bauhaus-era photographer Iwao Yamawaki, for example, who studied under Moholy-Nagy, and, in a small nook that serves as the gallery library, intimate publications by Nazraeli Press of Emi Anrakuji, who makes mesmerizingly confessional self-portraits, some of which are printed onto found postcards. The works are psychologically direct, but dense and full of layers. “I know it is impossible to understand what someone in another culture feels,” she says. “But ultimately, with strong and honest work, one doesn’t need to translate or even explain. It’s more like I facilitate. There are so many points of entry into a photo. I just bring people to the work. Then they decide for themselves.”