There’s a cool, ambient glow permeating Bryce Wolkowitz’s windowless, second-floor office, but it’s not emanating from the light fixture hanging from the ceiling (which, by the way, is missing a bulb). Rather, its sources are multiple: there’s a stack of four clear-resin copies of Charles Bukowski’s novel Pulp, over which excerpts of Bukowski’s text play, Times Square marquee-style, in red LED (an artwork by Korean artist Airan Kang); on the wall hangs a white-and-red neon sculpture that spells the word “enlighten” in bright, sinuous cursive (by Brigitte Kowanz); and of course there’s the 32-inch computer monitor on Wolkowitz’s desk. Downstairs, in his Chelsea gallery, a handful of technicians are putting the finishing touches on a projection of pixels-on-sand by Shirley Shor for an exhibition called, Altneuland (Old New Land), an apt metaphor for Wolkowitz’s foray into things luminous.

“When I opened in 2002, new media was still very much in its infancy,” he says, “certainly as a commercial entity. I didn’t know in those first few years that this vision I had of what I wanted to promote would have legs. Now, it’s firmly embedded in the market. I’d like to think we’ve helped to contribute to that.”

Wolkowitz, 37, is slim, bearded, blue-eyed, his demeanor an unlikely mix of smooth confidence and wide-eyed wonder. He grew up on New York City’s Upper West Side (where he still lives), the son of two Pop art collectors whose taste (Andy Warhol, Jules Olitski, Kenneth Noland) got him accustomed to being surrounded by challenging art. Progressive institutions like the Ethical Culture School and the Fieldston School formed Wolkowitz’s early education, but it was a summer spent abroad at Oxford, where he took a photo history course with George Tucken, that fired his imagination. “I can remember the trajectory of that course to this day,” says the dealer. “When I came back I began collecting photography with my father. I was hooked.” By the time he was 15, Wolkowitz had posters of works by Moholy-Nagy and Man Ray over his bed, and he was attending auctions at Sotheby’s. “The Graham Nash Sale was one of the earliest,” he says, “I can remember the spotlight that sale put on the photo market, and then, every year after, seeing these new benchmarks being met.”

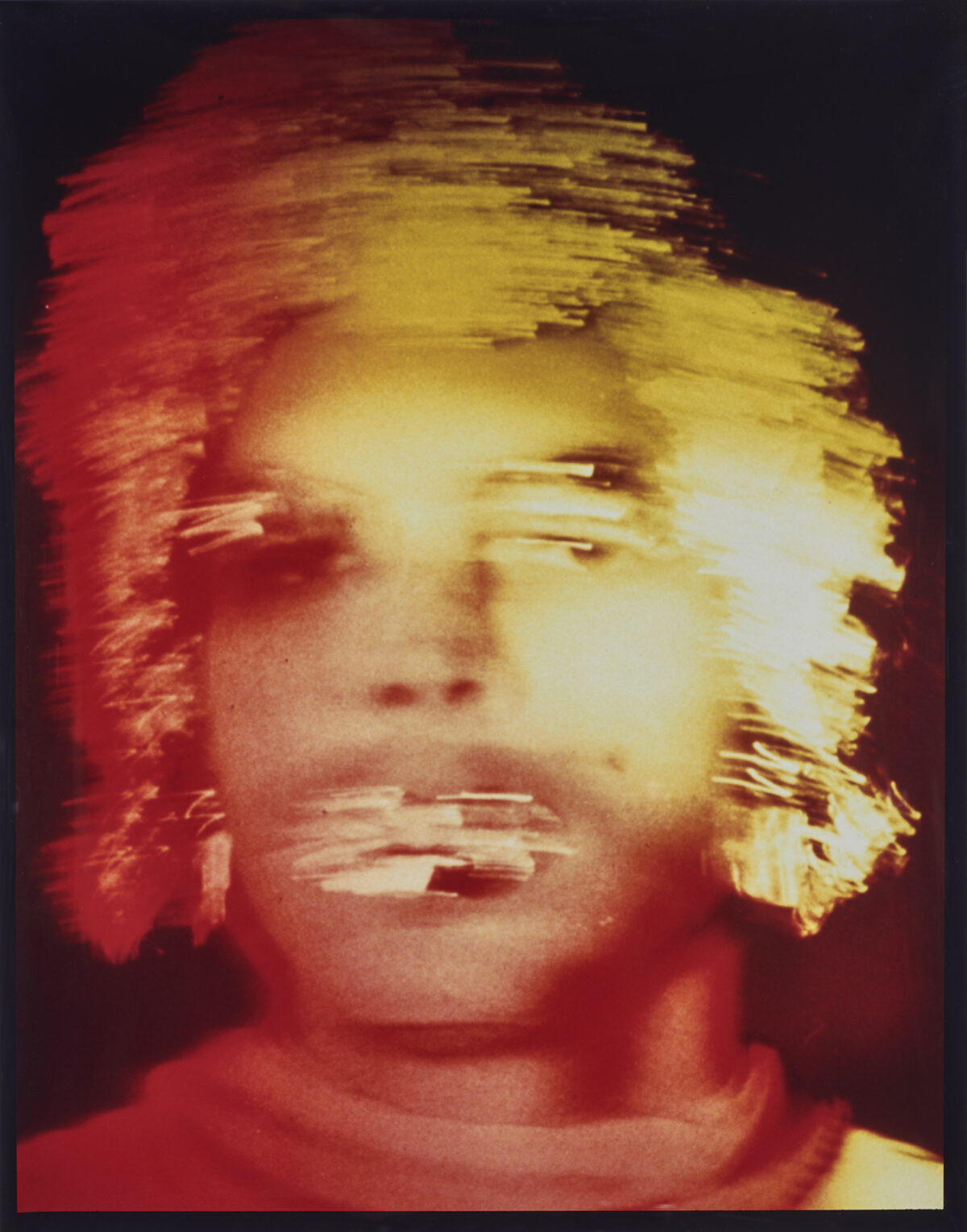

By the time he got to Vassar, Wolkowitz had already formed the strong sense that he would work with contemporary photography. Graduate school, at the NYU-ICP joint program, and an internship with John Hanhardt at the Guggenheim, refined his tastes—and goals. “I went into NYU wanting to get my hands dirty and understand what the process of making a photo is all about; I came out making and studying video. Nam June Paik, Tambolini, Nauman, Viola: John really opened my eyes to the history and potential of this medium that was only 40 years old. I looked around at the programs of other dealers and figured out what sort of platform I might have that would be unique.”

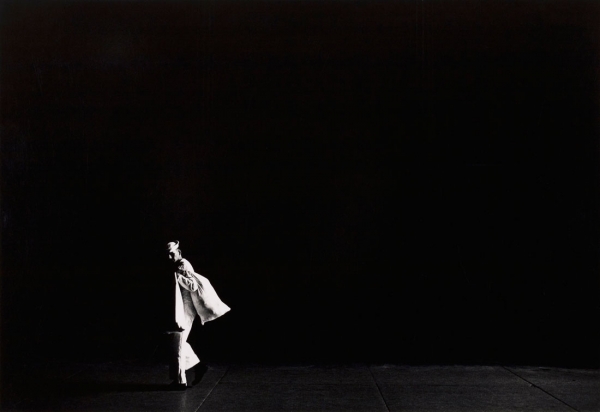

After graduating, Wolkowitz worked as a specialist in Christie’s photography department, then in 2002, went into business for himself. His stable quickly swelled to include straight photographic works by Edward Burtynsky, canvas and wallworks by José Parlá, and ambitious projects like Jim Campbell’s Scattered Light, an 80-foot-long assemblage of 2,000 bulbs equipped with micro-processors that projected, depending on your vantage point, the eerily blurred forms of incessantly moving pedestrians. “Campbell is into the liminal, into how much information can our eyes or brain discern. Ultimately,” says the dealer, “you start to put the story together yourself.”