Photo by Lorraine Koziatek

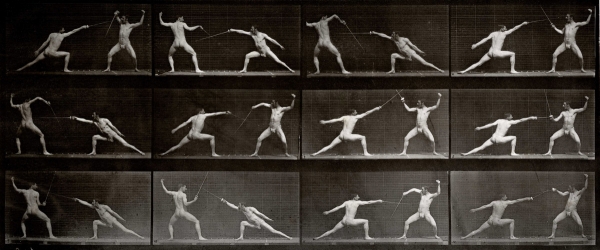

Sometimes what makes a dealer’s sensibility so attractive is the fact that it can’t easily be summed up. Take Laurence Miller, for example. His gallery on 57th Street, long respected for its shrewd mix of mid-career artists and undersung modern masters, just marked its 30th anniversary with a show that, at first blush, couldn’t be more diverse: a color-saturated and psychologically bizarre photolithographic image by Robert Heinecken that (loosely) depicts John Szarkowski; a Val Talberg black-and-white multiple-exposure body study; a classic street scene by urban master Helen Levitt; and a composite by Ray K. Metzker (the artist who forms the keystone of Miller’s stable): tiled photo stills of an elderly man and woman going up and down stairs in mesmerizing rhythm. Says the dealer, “I want a picture to be self-sustaining and not tell the audience what it means but invite the audience to bring their own meanings. I think wall labels are a trap. Good photos should teach you something you don’t know, a new way of seeing the world.”

Miller, 65, was born in Manhattan and raised in Huntington, Long Island, where he passed a happy suburban childhood. His father (a general contractor) and mother (a housewife who was passionate about civil rights) gave Miller and his older sister the freedom to be who they wanted to be. Winters meant sledding on the nearby golf course, and summers were spent working at the local marina. Miller attended the University of Wisconsin, Madison, in the socially conscious 1960s, where he thought he’d prepare for a career as a civil-rights lawyer. But he took a year off to explore, attended the 1969 march on Washington, and hung out with artist friends from Brooklyn. Miller returned to Madison, discovered photography under the tutelage of photographer Cavalliere Ketchum, and wound up getting his B.S. and M.A. there. He went on to study under Beaumont Newhall and Van Deren Coke at the University of New Mexico in Albuquerque, and he eventually came to the realization, he says, that, “I’m better at editing and hanging shows than at taking pictures.” One of his teachers suggested he get a job at the Light Gallery in New York, and he stayed on as associate director for six years, making his first connections with Harry Callahan, Aaron Siskind and, most importantly, Metzker.

By 1981 Miller was ready to go into private dealing: “I had no grand design, no sense of what would make money. I just wanted to show work that was important, that I liked.” He built a portable print-rail area behind the couch of his one-bedroom Greenwich Village apartment for presentations and spent most of his time on the road. Miller opened a gallery in 1984 in an intimate space on East 57th Street, moved to SoHo in 1986, and by 1999 moved to his current digs on West 57th Street. His wife, Lorraine, has managed the gallery’s finances since the beginning. “Throughout my desire to be a civil-rights lawyer,” says Miller, “I realized that what I really desired was to be a different kind of advocate, for people like Levitt and Metzker and Fred Herzog. When I took them on they were innovators, who were out of fashion. They deserve the recognition, and I try to give them the context they deserve.”