They say you can tell a lot about a person by what they like. But Yossi Milo’s taste is not so easily defined. If you had to describe it, you might say the 38-year-old Israeli-born photography dealer—whom most observers agree has his finger on the pulse of a new breed of contemporary photographers—favors work that’s a bit mysterious, work that keeps something of itself in reserve.

The solo show of large-scale color prints by Martina Mullaney that kicks off Milo’s move in Chelsea to a ground-floor space on West 25th Street this month is a case in point. Mullaney, a Royal College of Art graduate, spent a year visiting hostels and shelters around England, Ireland, and Wales photographing the beds where indigent people had just spent the night. But rather than being simply documentary or diaristic, her prints are more about abstract notions of color and light: a few gentle ripples in a white sheet, a slight shift of color or a scuff on a wall. “I love the perfect composition, the perfect coloring and texture—they are like paintings, actually,” says Milo. “But most of all, I am interested in their psychological quality. She is trying to make these images as beautiful as possible, and there is something disturbing in that.”

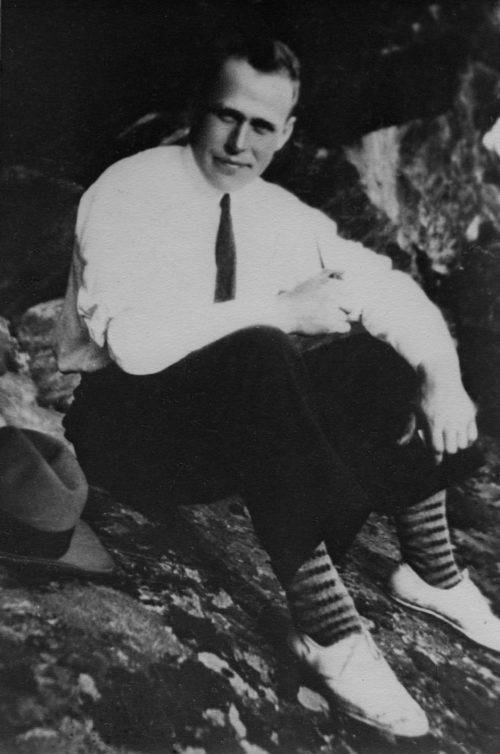

Milo, his black sweater and slacks picking up his dark hair and features, cuts a figure that is sleek but not slick. Three years of serious art history study in a boarding school near the Ein Hod artist colony in the Carmel Mountains of Israel in his youth were enough to ignite an interest in a career in the arts. But when he moved to New York at the age of 22, after a completing his tour of duty in the Israeli army, Milo studied business and psychology at Baruch College. Not exactly the sort of background one expects from a dealer as on top of his game as Milo.

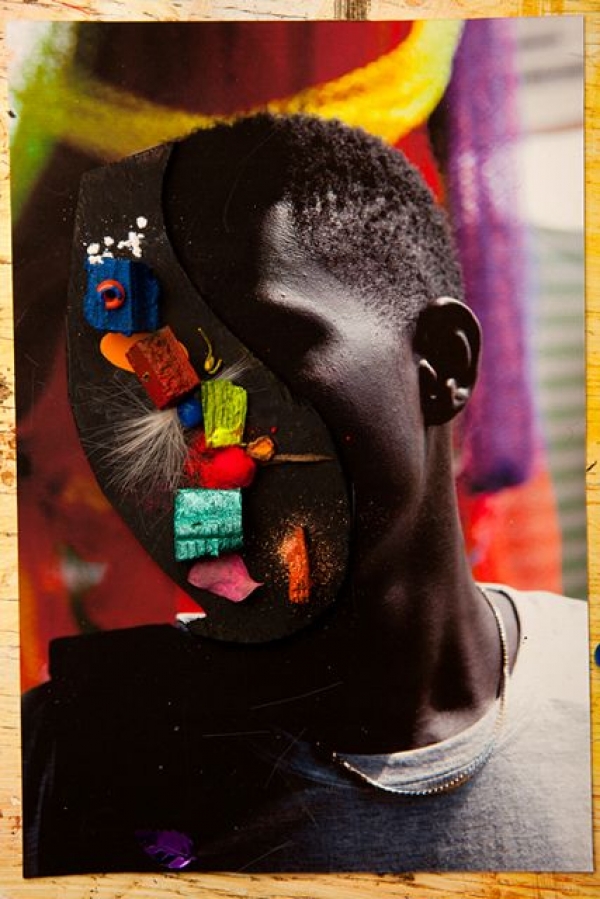

Milo takes his artists’ portfolios out of the flat files one by one. And as they emerge, each seems a non-sequitor that, when taken together, make for a lively dialogue on what’s happening in the medium today. There is Paris-based Lise Sarfati, whose photographic portraits have the au courant preoccupation with dissolute youth down pat—yet without being derivative or dull. There is Irish artist Trish Morrissey, who recreates the settings and dramatis personae of her old family snapshots in the present day: a birthday party, parents with a new baby—all are marvelously vernacular moments writ large and lush. And German-born Loretta Lux, via painstaking digital manipulation, cobbles together fragments from disparate female figures. But unlike most of her contemporaries, she does this seamlessly, with a painterly respect for qualities of light and setting. Here Milo admits to an infatuation with new media—and the possibilities it holds in the hands of artists like Lux. “The way she makes their eyes vivid, porcelainizes their skin, enlarges their heads, narrows their shoulders,” says Milo. “They are like something out of Bronzino or Balthus.”

By 2004 Milo had placed Lux’s work in more than twenty international museum collections, and scheduled her for six big international shows in 2005. (This spring, Lux’s first monograph by Aperture is due for release.) And other artists he represents have had similar success. Alex Soth was tapped for the 2004 Whitney Biennial, and 35-year-old Argentinian artist Alessandra Sanguinetti got oodles of press coverage this fall, including a portfolio in Blind Spot. Milo knows what he likes, and what he likes seems to strike a chord with others—without reservation.