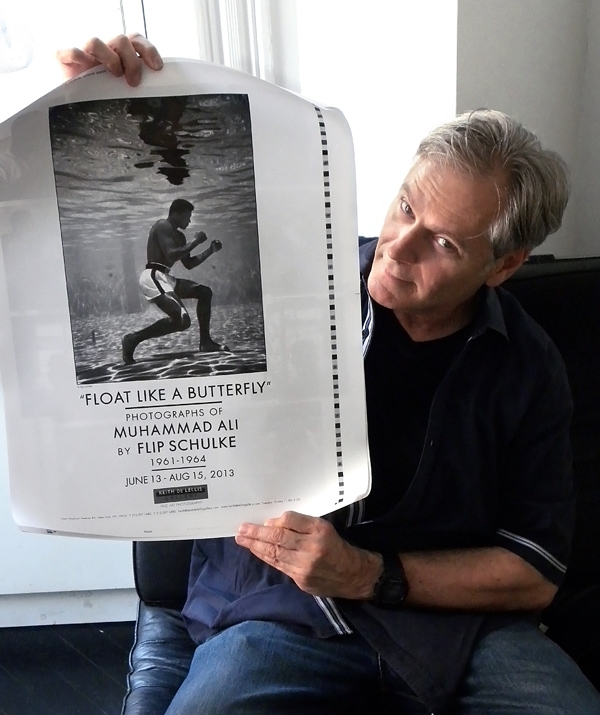

Supposing you found a treasure hiding in plain sight. Would you shout it from the rooftops? Would you bury it in the sand? Keith de Lellis, a photo dealer with almost preternatural instincts for 19th- and early 20th-century material, would know exactly what to do. Before he even went to high school, he’d been descrying photographs of value before others woke up to their worth, contextualizing them for the public and selling them. There was the time in 1970 that he got in early to the 26th Street flea market and spotted a rare daguerreotype of a Chinese woman playing a lute. He bought it for $15, and then sold it the same week for $100. Not a bad day—for a kid of 15. “Today that image could be worth as much as $100,000 were it even on the market, but it’s not,” says de Lellis. “It’s in the Getty Collection.” Thirty years of dealing hasn’t diminished the thrill of photographic discovery for de Lellis. “You have to sell to buy more. If you’re not selling things, you’re a collector.” However, he admits, gesturing to the impressive inventory filling the office of his Madison Avenue gallery, “I’m still a collector at heart.”

De Lellis, 57, green-eyed, with greying hair and a calm demeanor, grew up in Forest Hills, Queens, where his mother was an art teacher and his father the executive director of the local Police Athletic League. From the time he was 12 he worked after school, saving the money he earned at an impressive $1.35 an hour. A course in summer camp introduced him to photography, and when he wasn’t shooting and developing pictures, he was reading all he could about the medium—especially its market. “The first big buy that I made was on summer vacation with my parents,” says de Lellis. “We went into an antiques shop in Quebec, and I saw a box of cartes de visite for 15 cents each. I made a deal with the shop for 10 or 15 dollars for the entire box. That box started my business.” He took out ads in The Antique Trader and mailed lists of his inventory to curators, collectors, and other dealers. He attended meetings of the American Photographic Historical Society, socializing with Metropolitan Museum of Art curator Weston Naef and collector George Rinhart.

By the 1980s, he was enrolled in Brooklyn College by day and selling to the likes of Sam Wagstaff on his own time, but de Lellis’s grades were flagging. A visit to a discouraging school guidance counselor gave him the final push, and he left Brooklyn College to become a private dealer full time, looking not so much for big names as for big talent. His tastes have educated a growing market. He re-discovered early color photographers like Ruzzie Green and H.I. Williams; advertising photographers like Lejaren Hiller; and modernist photographers like Gordon Coster and Edward Quigley. In 1997, de Lellis went public, first on East 68th Street, and later at 1045 Madison Avenue. “People have become so name and brand conscious,” observes de Lellis, “which is why I’m more involved in predicting what museum curators will want these days than in what they say they want. You know what Diana Vreeland said: ‘You have to give the people what they don’t know they need yet.’”