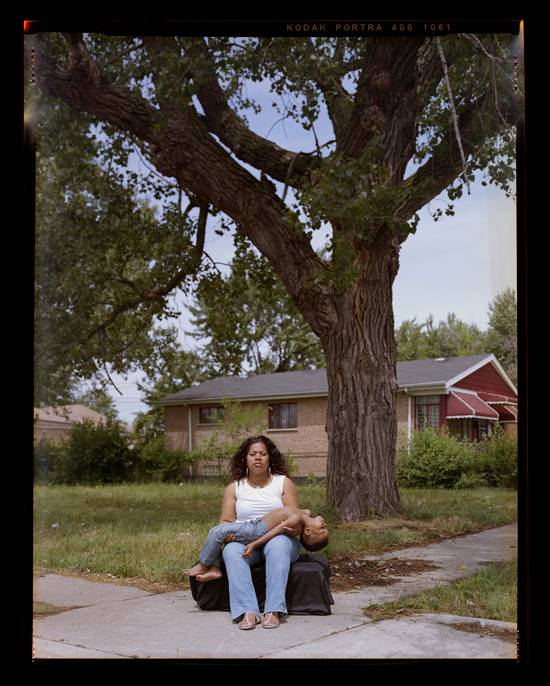

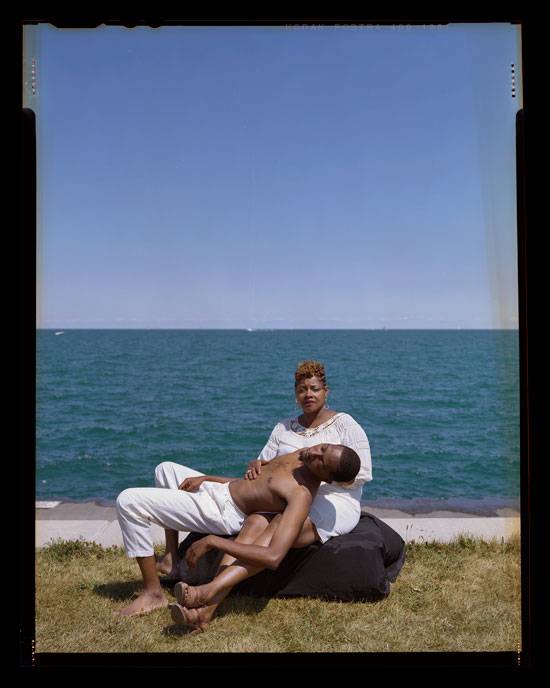

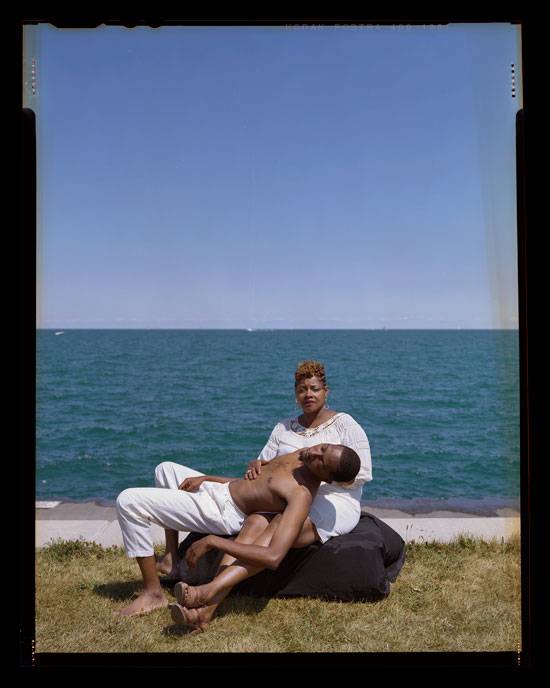

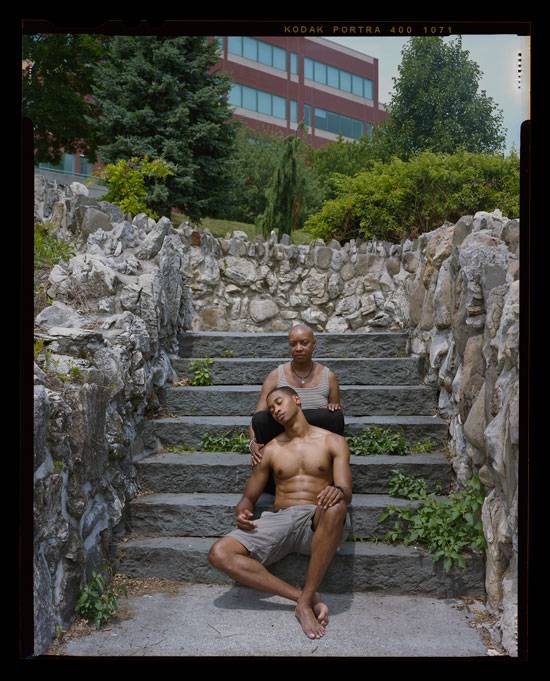

Jon Henry is the recipient of the 2020 Arnold Newman Prize for New Directions in Photographic Portraiture for his series Stranger Fruit, portraits of Black mothers holding their sons in poses that suggest the pietà. Selections from the series are on view at the Griffin Museum of Photography through October 23. Born and raised in Queens, NY, Henry says the idea for the series, which he began in 2014, first came to him after the murder of Sean Bell in 2006 by police, on the morning before his wedding in Jamaica, Queens. “It felt like it could have been me or any of my friends,” he says, adding, “I’m 38, and to this day, my mother tells me to be careful; she still worries.” The religious iconography comes naturally to Henry, who was raised in St. George’s Episcopal Church in Flushing, Queens, where he had a photo studio and worked as a sexton. The church is the setting for the first photograph in the series.

On the occasion of Henry’s exhibition, I spoke with artist and writer Qiana Mestrich about Stranger Fruit. Mestrich’s critical writing has been published in photo journals including En Foco’s Nueva Luz, Light Work’s Contact Sheet, and SPE’s exposure. Mestrich is the founder of Dodge & Burn: Decolonizing Photography History (est. 2007), an arts initiative that aims to decolonize the medium by advocating for Black, Indigenous, and other photographers of color. A graduate of the ICP-Bard College MFA in Advanced Photographic Practice, Mestrich is adjunct faculty in photography and social media at the Fashion Institute of Technology (SUNY).

Jean Dykstra: Qiana, when did you first see images from Stranger Fruit, and what was your initial response?

Qiana Mestrich: I first saw the photographs a couple of years ago, probably following, unfortunately, the murder of Tamir Rice [the 12-year-old Black boy killed by police in Cleveland in 2014]. Having studied art history, I immediately got the reference to the Christian iconography of the Madonna and the pietà, Michelango’s especially. But also being a historian of photography, I was immediately brought to Renee Cox’s image, Yo Mama’s Pieta [1996]. As much as her work is known, I still feel like it’s not as known as it should be. Renee was on the forefront of many issues in her work early on, dealing with family and motherhood and different types of family structures, and Jon’s work definitely reminded me of Renee’s in that sense.

JD: It’s great that Renee Cox resonated with you. She does fly under the radar a bit, but he has said she was an influence for this series.

QM: I’m sure – I don’t know how he could have made those images without knowing her images.

JD: It can be easy to look at Stranger Fruit and think that it’s so timely. But it’s not, unfortunately.

QM: It’s not. Certainly in photography, there’s a history of lynching photographs, lynching cartes de visite – this whole culture that was created around lynching as a photographic event. And so I see his work as part of that visual conversation. In terms of the lynching photographs, certainly someone would have been there to collect the bodies of these Black people who were lynched, possibly mothers would have been there to collect the bodies of their sons. You could almost look at his work within that same visual narrative of this horrific violence against Black bodies that is so prevalent throughout the history of the medium

JD: I was formulating a question about images of violence and Black bodies, when I came across this quote from Imani Perry [the Hughes-Rogers Professor of African American Studies at Princeton University]: “ … the question, for me, is both how do we acknowledge the social reality of deep inequality, of mass incarceration, of death of innocent Black youth, and also recognize that it’s important to assert and reassert the full humanity and beauty of their lives, and also to offer them a vision of their lives that is meaningful.” The issue I was thinking through has to do with how these painful images are received. There is so much beauty and tenderness in them, but their essential subject is violence against Black bodies.

QM: There’s definitely both the tragedy and the beauty in these images. I didn’t realize at first that in part of the series you see just the mother, isolated – they’re also quite beautiful and speak volumes about an interior mental and spiritual state of Black motherhood and Black single motherhood as well. Having grown up with a single Black mother as a single child, and having seen my mother be the sole parent and witnessed the struggle but also I also saw how much power she had to summon forth to keep going and the strength in that. So I think these portraits of the mothers are just as important. You get a completely different sense of the work when you see these in context with the pietà images. You get a much more complex sense of these women in their domestic environments, and then you see the images of them with their sons. It’s interesting – the posing of the images, with the sons being shirtless, is a very specific choice.

JD: How do you read that choice?

QM: It’s clearly, for me, a reference to flesh. They’re also barefoot, so for me it’s essentially again a reference to the historical act of lynching. The title of the series, of course, is a reference to the song that Billie Holiday made popular – Strange Fruit. I would say it’s a historical reference to have them shirtless and barefoot, but then they’re wearing denim, which is a fairly modern clothing, so there’s this shift in time. There’s a way that the images work in terms of shifting back and forth from history to present time.

JD: If the images are quoting the pietà, then the son is a stand-in for Jesus, so in that sense you can read the Black body as the embodiment of Jesus, or of a body made in God’s image, so that the composition is tragic but there’s a sacred and beautiful aspect to it as well, an insistence that the Black body is a cherished body.

QM: I was raised Buddhist, so I still baffle over not just the iconography but the constructs of Christianity. This person died for us, for our sins – that was always something I struggled with, placing so much importance on the fact that someone was crucified for the sake of our lives, our humanity

JD: It is certainly a violent iconography and a brutal act at the center of a religion. One of the other things I really appreciate about this series is that Henry is very intentional about making the images all over the country and in all sort of settings. That really resonates with me in terms of suggesting that this is a phenomenon that crosses geographical and economic boundaries.

QM: Right, and the portraits of the mothers with really young sons are really interesting as well, and especially painful. But again, for me, that speaks to not just lynchings but the inequality of medical treatment that Black women and Black mothers receive, or don’t receive. It really speaks to the frailty of Black motherhood in that sense, when we see these young babies in their arms. The precariousness of being a Black mother and having Black children at any stage, not just teenage boys. The locations are great – there’s one of a mother in front of the capitol, in Montgomery, AL, in front of an official government building. And she’s specifically sitting on the brick road that leads up to the steps – it’s very powerful.

JD: Were there other specific images that stood out for you?

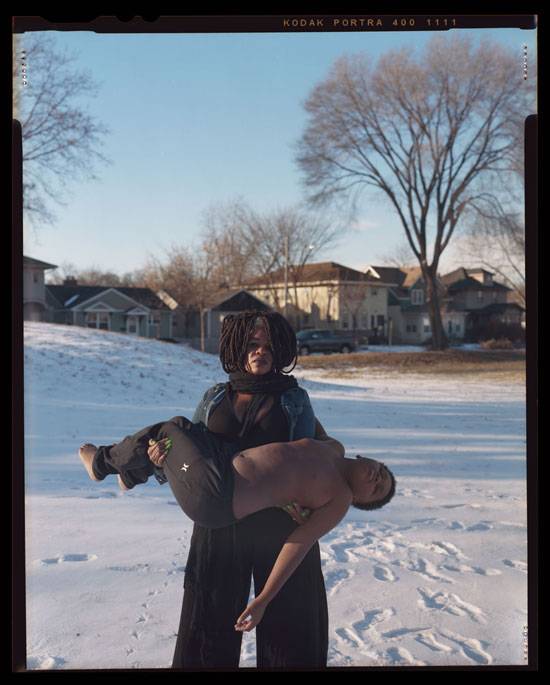

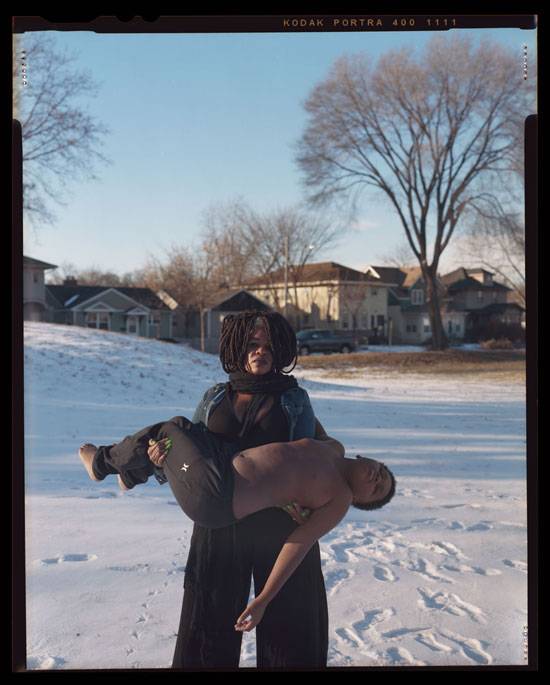

QM: I really loved Untitled #35, Minneapolis, MN, with the mother in the snow, and you can see footsteps in the snow as well. I just instantly start visualizing stories, and you see the trees in the background, and the footprint of those trees on the image is really interesting as well. They’re really gorgeous. As much as his images are formally staged, there’s an informal element to them as well, so they function as formal portraits but also as candid documentary images as well.

JD: Henry has spoken about the importance of having images of Black bodies in works of art created by a Black artist, being shown in galleries and museums. But he also talked about the importance of having the images in other spaces, in public art projects – phone booths, for instance – that make them accessible to a wider audience.

QM: It’s also that as a non-white photographer, it’s something that we think about, in terms of who our audience is. As Ming Smith has said, we don’t necessarily have the privilege of making images just for the sake of making images. There’s no immediate market for our work, and we have to make the work simply because we have to make the work, but we also have to consider multiple audiences. And so he’s making this work not just for a gallery but to insert his voice into the history of the medium, which historically has not included Black photographers – even though there have been Black photographers since the creation of the medium. But those voices have not traditionally been valued. So there’s always this thought of having to make work for multiple audiences and multiple reasons.

JD: In a talk Henry gave recently, he ended with a call to action: what are you going to do? I think that challenge is somewhat inherent in these photographs.

QM: Right – it’s like, what’s next? What will you do now, after seeing these images?