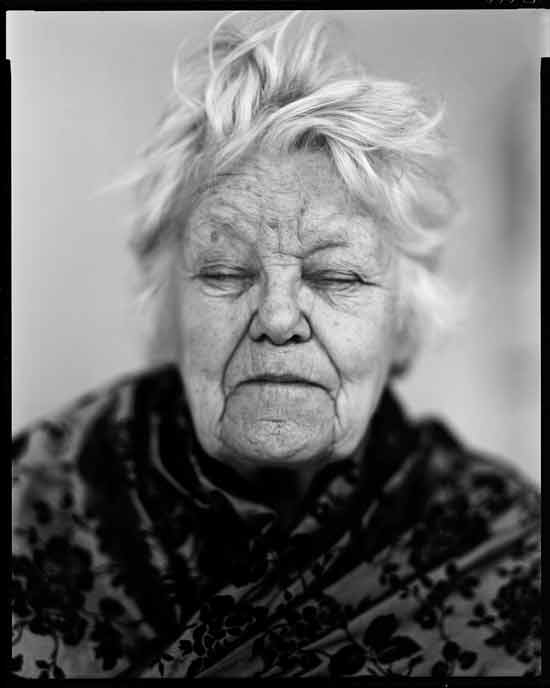

After photographer Cheryle St. Onge’s mother, Carole, was diagnosed with vascular dementia about five years ago, St. Onge stopped making photographs. Overwhelmed and grieving the loss of the mother she knew – whom she calls “the greatest person on the planet” – she was slipping into depression. Carole had lived for some 20 years with St. Onge and her husband and children in a separate apartment on their Durham, New Hampshire, property, and she was an integral part of their lives, helping ferry her three grandchildren to lessons, gardening, joining her daughter on errands. St. Onge’s friends encouraged her to pick up her camera again and to photograph what she was going through with her mother, and about two years ago, she did. The result is Calling the Birds Home, a series of poignant, intimate images, mostly in black and white, of Carole, a former college administrator, artist, and painter.

St. Onge is an only child. Her father died in a car accident when he was 39 years old and her mother never remarried. Her father was a physics professor, and St. Onge grew up on college campuses, with a lot of time spent outdoors, exploring, with her parents. “I had a beautiful childhood,” she says. Now, in a shifting and slipping of roles that many adult children confront, she has become the caregiver to an increasingly childlike parent. “A lot of people have been through this, but I’m still on that road,” says St. Onge. “I’m making work about something that is unfolding day by day.”

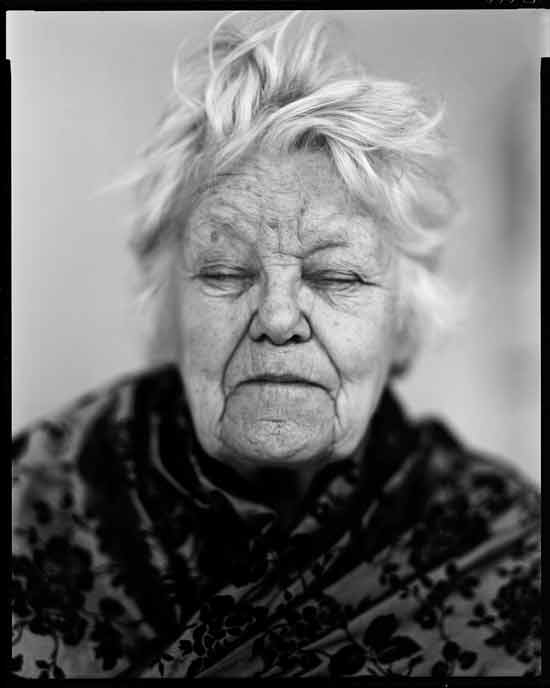

The photographs are collaborative to a degree: Carole is a willing participant in the project, though she doesn’t recognize herself in the photographs. Some of St. Onge’s photographs are simple and quiet – her mother sitting in the sun, eyes closed, surrounded by bright yellow forsythia branches. Others are more playful or more choreographed. In the vein of Sally Mann’s photographs of her children, they draw on a lifetime of trust and affection. Her mother blows soap bubbles through a plastic wand, makes a snow angel wearing a fur coat, or buries her nose in fistful of flowers. In one portrait, the floral wrap around Carole’s shoulders is in soft focus, while her face, her eyes closed and her expression unreadable, is in sharp relief, as though everything decorative – or decorous – is falling away in the face of this disease. But for St. Onge, the photographs open up a way of communicating with her mother, an exchange that had been lost to the dementia. One particularly beautiful photograph is a close up of Carole and a horse, their faces pressed together, side by side. The image – framing the horse’s huge, long-lashed eye, and Carole’s small smile – radiates something like peace, fleeting as it may be.