In 1988, Sheila Metzner made a photograph of a single metal sphere resting upon a neutral surface. The image is handsome, if unremarkable, but its title, Time, nudges it from the straightforward into the metaphorical or even the metaphysical, inviting us to read the picture as something more than a formal conversation between plane, volume, light, reflection, and shadow. Metzner names, as the picture’s true subject, photography’s essential, ever-mystifying power to suspend our orb’s spin for a moment, just long enough to ruffle our view of the world as fixed, knowable.

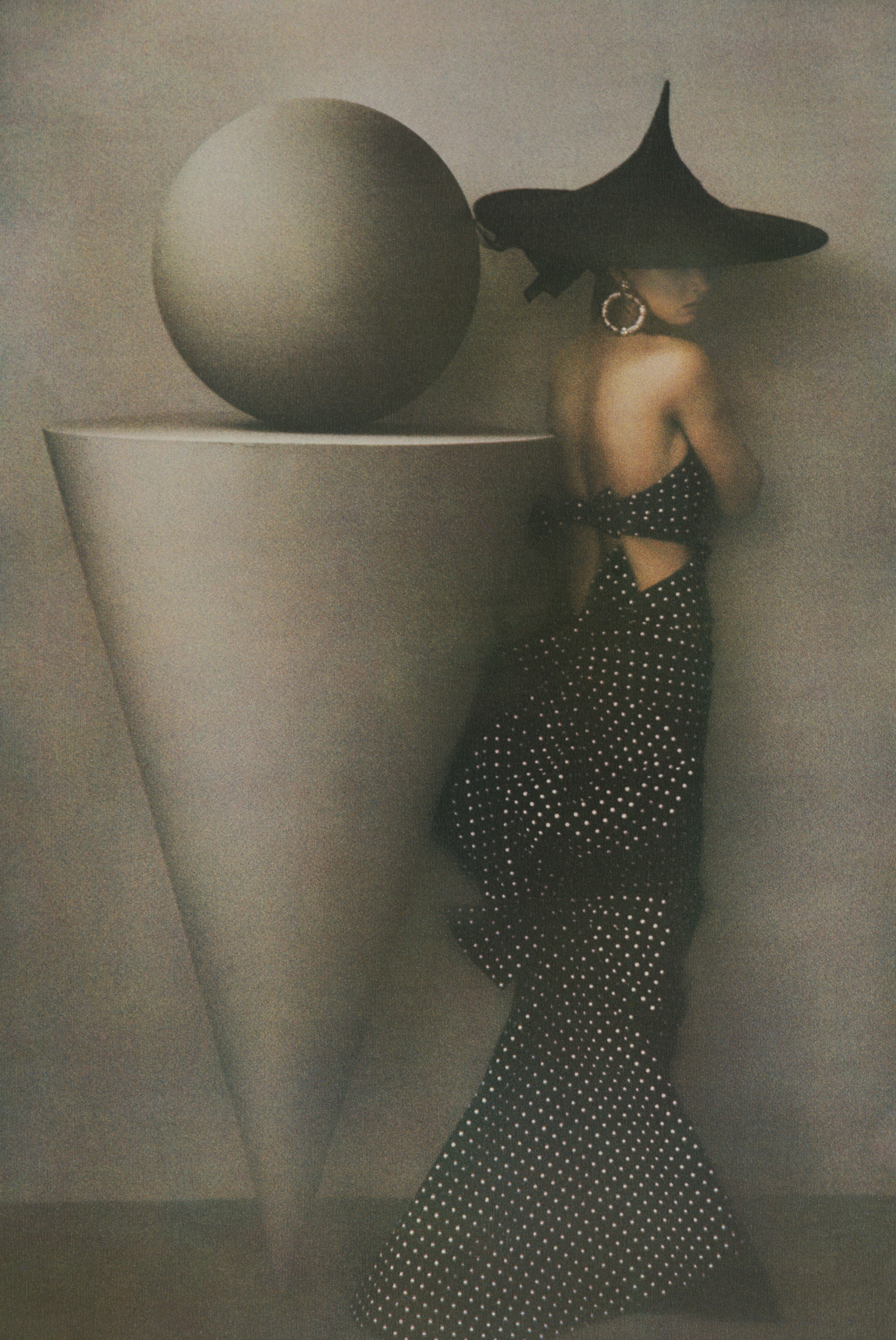

The two Metzner shows running concurrently in Los Angeles – From Life at the Getty Museum through February 18, and Objects of Desire at Peter Fetterman Gallery through January 5 – don’t include that particular picture, but a preoccupation with time pervades all the works on view, whether they’re from that same still-life series (Metal Objects in Time and Space), or among the artist’s portraits, fashion shoots, or landscapes. Metzner has made a career of obeisant nods to the past, paying homage to predecessors (Man Ray, Edward Steichen, and others) and adopting the century-old Fresson printing process, whose dreamy, grainy softness became her signature look. The process, invented by Pierre Fresson, involves successively exposing and developing an image from a single negative using gelatin and four pigments – cyan, yellow, magenta, and black.

Discussions of Metzner’s relationship to time have dominated the work’s critical reception, with some writers praising her neo-Pictorialist style as timelessly elegant and others disparaging it for being just the opposite – statically time-stamped, airlessly anachronistic. The poet Mark Strand evinced this ambivalence in his otherwise laudatory introduction to one of Metzner’s books, describing the light in her photographs as “a kind of airy amber” but also calling the staged space within them “tomblike.”

The Getty show, curated by Paul Martineau, positions Metzner as an artist “closely associated with the best of 1980s fashion, beauty and decorative arts trends” (as stated in the wall text), but otherwise doesn’t address any temporal slippage within or around the work, or why Metzner’s vision might remain relevant today. Undisputed are the impressive milestones of her professional career.

Born in Brooklyn in 1939, Metzner studied communication arts at Pratt Institute and entered the field of advertising after college. Smack in the middle of the Mad Men era, she became the first woman to hold the position of art director at the major firm Doyle Dane Bernbach. In 1968, she married, leaving her day job to raise a large, blended family, including five children of her own. In the slim window of solitude after the children went to bed, she taught herself photography, inspired by Julia Margaret Cameron’s domestic-centered practice. “If Cameron could have five children and take pictures, I could too,” she told the Los Angeles Times. Like Cameron, Metzner photographed both family members and other notables, and signed her pictures, “From Life.”

She made an auspicious first public appearance in the landmark 1978 MoMA exhibition Mirrors and Windows: American Photography Since 1960 and had two solo shows at the Daniel Wolf Gallery in New York City immediately thereafter. Fashion and editorial assignments proliferated, and her commercial career flourished, earning her a slew of awards. Metzner put what former ICP curator Carol Squiers described as her “sumptuous, romantic vision” to work for Fendi, Chanel, Ralph Lauren, Valentino, and numerous other upscale clients. Vogue kept her under exclusive contract through the ’80s, another rare achievement for a woman at the time.

The Getty show surveys more than three decades of Metzner’s career in some 40 pictures; the presentation at Fetterman numbers just over two dozen photographs and concentrates largely on fashion and floral studies from the ’80s and ’90s. In the floral still lifes, single blossoms prevail, isolated and tightly framed, or in Art Deco vases, the colors wistful. Metzner’s compositional approach tends to be direct and spare, modestly sensual. Luscious tonalities and velvety textures come courtesy of her printing methods. Metzner’s pictures of women land on the same continuum as the floral still lifes, for the most part. In shallow spaces, languorous models are staged as exquisite decor.

Joko, Passion (1985), one of the few images to appear in both exhibitions, is a refreshing anomaly for its disjunctive and playful spatial complexity. Metzner wryly juxtaposes a live model and a painted nude, both seen only partially. Their torsos enter the picture from opposite sides and their heads nearly meet but for the vertical gold stripe between them, the left edge of the painting’s frame, articulating an uncrossable perceptual and physical boundary. At that junction sits a vase holding a single protea flower and a mismatched leaf so strangely large that it covers the whole of the painted figure’s face, as if concealing a secret. In stark contrast to the cloistered, harmonious space of most of Metzner’s photographs, Joko is intriguingly unresolved.

Metzner’s early photographs of her family are certainly tender, but her work in other genres is characterized by a studied, hushed detachment, both emotional and temporal. Her subjects are, indeed, “From Life,” but Metzner transposes them elsewhere, to the realm of idealized memory or an imagined, friction-free parallel universe. Her firstborn, Raven, has written that the pictures “are meant to seduce you into dreaming a better world into existence.”

Looking backward, dreaming forward – these states aren’t easy to reconcile. Nor were they ever for some viewers encountering Metzner’s work. Gene Thornton, writing in 1978 for the New York Times about the artist’s first gallery show at the Daniel Wolf Gallery, registered shock that someone inclined to the kind of surface emphasis found in Metzner’s work was born in the mid-20th century. “Even before World War I,” he wrote, “this type of photography was out of touch with the times.”

Art and artifacts can only ever be of their time, however. A show that explored the impulses behind Metzner’s mannerism, that examined the dissonance between the visual domain she contrived within her studio and the actual social landscape beyond, a show that dug a little deeper – that could bring Metzner’s work closer to life.