Raghubir Singh, the Indian photographer who died in 1999 at the height of his jam-packed colorful career in India, Europe, and the United States, was not only highly quotable but also fond of quoting others: In River of Colour (Phaidon), the book that came out the year before he died, Singh quoted the Bengali poet Rabindranath Tagore on the topic of, yes, quoting and borrowing: “Only mediocrities are ashamed and afraid of borrowing for they do not know how to pay back the debt in their own coin.”

Singh sure knew how to borrow. He embraced a cross-cultural gamut of artists, from painters (Diego Velázquez, Rajput miniaturists) to writers (Vladimir Nabokov, V. S. Naipaul) to film directors (Pier Paolo Pasolini, Satyajit Ray). And there were plenty of Western photographers he admired and copied, including Henri Cartier-Bresson and Lee Friedlander. But his distinctive, democratic style came as much from his rejections as his embraces. And I mean rejections of him as much as by him.

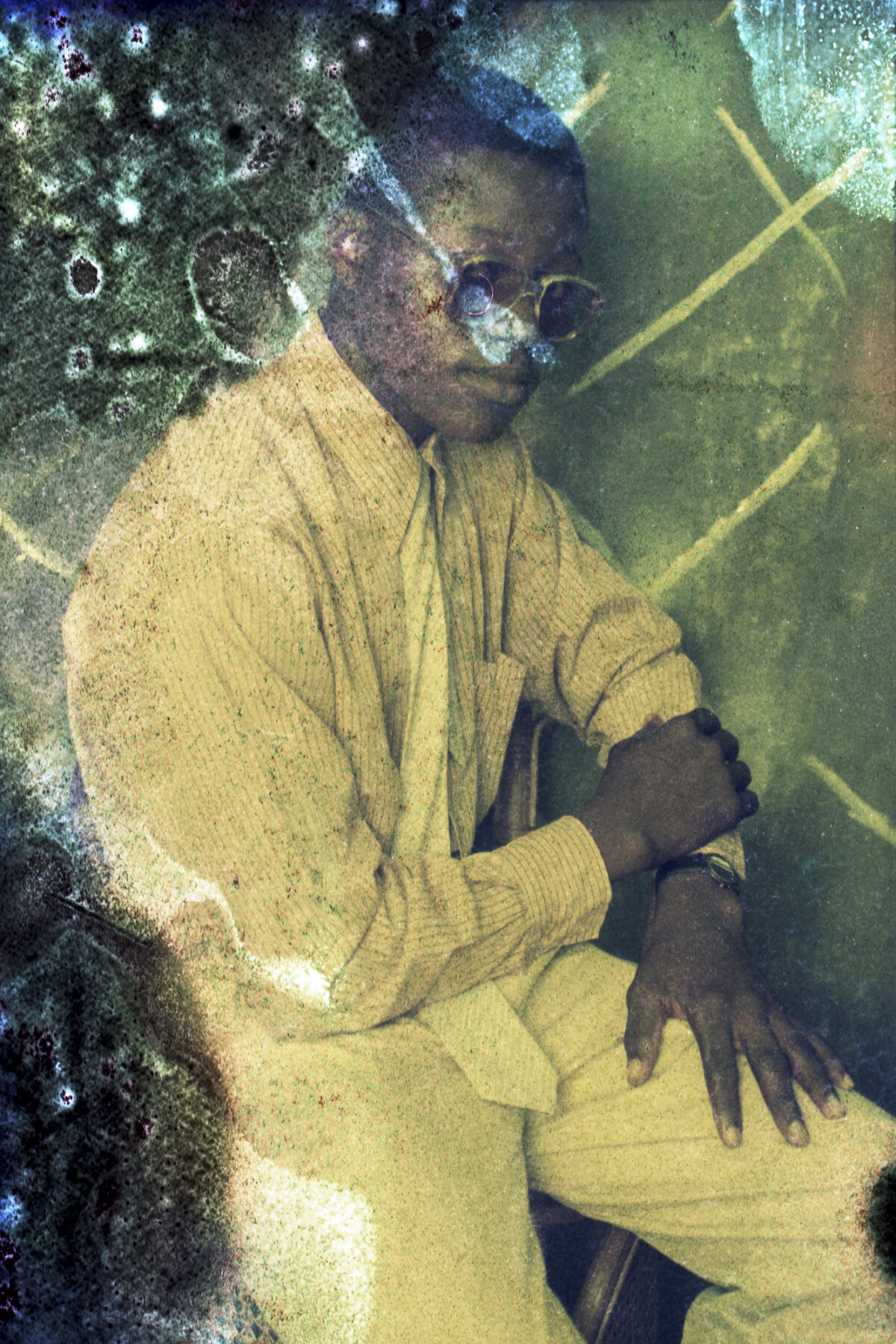

Born on October 22, 1942, in Jaipur, Singh got his first camera from his older brother at the age of 14. He began learning photography by copying the pictures he saw in Life magazine, and he soon became so passionate about photography that, as he once put it, his “heartbeat ran an umbilical cord” to his camera.

His first important rejection came from, of all places, the tea companies of Calcutta. After high school Singh planned to join his brother in the tea industry, as Mia Fineman, the curator of the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s retrospective Modernism on the Ganges: Raghubir Singh Photographs, opening October 11 at the Met Breuer, writes in her excellent catalogue essay: “But after he was rejected by every tea company to which he applied, Singh switched to Plan B: a career as a professional photographer.” Hooray for rejection!

Soon Singh began shooting pictures on Calcutta’s streets. In 1961, he met the great Bengali filmmaker Ray, who was already famous for his Apu Trilogy. In time, Fineman writes, “Ray would become a lifelong friend and mentor and, most importantly, a model for reconciling Western modernism and Indian aesthetics.” (Ray’s Apu Trilogy told a Bengali story with the filmmaking techniques of Italian neorealist Vittorio De Sica.) But first came another rejection. As Partha Mitter, an emeritus art historian at the University of Sussex, reports in the catalogue, when Singh showed his color photographs to his hero, he overheard Ray assessing him to another guest as Singh left the apartment: “No guts.” He let the criticism sink in.

By the late 1960s, Singh had become a successful – and sometimes gutsy – photojournalist, working for The New York Times Magazine, Life magazine, and National Geographic, which gave him as much Kodachrome slide film as he wanted. In 1974, Singh went with a film crew to North Sentinel Island in the Bay of Bengal to take photographs for a documentary called Man in Search of Man. As they approached the island, they were shot at with bows and arrows (though they ultimately made peace with their subjects and were able to make photographs of them). The next year Singh went back to a nearby group of islands to photograph the indigenous Negrito tribes. This time he got full access, making one of his most memorable photographs – an image of a nearly nude Jarawa woman dancing exuberantly on the beach, which ran on a full page in National Geographic. Nelson Mandela loved it so much that, to cheer himself up, he tacked the page up in his prison cell.

In 1966, Singh met the great Magnum photographer Henri Cartier-Bresson when they were both in Jaipur to photograph Indira Gandhi, India’s new prime minister. Singh, aged 23, followed Cartier-Bresson around Jaipur and soon began working with Cartier-Bresson’s signature cameras (Leicas and Nikons with 28mm, 35mm, and 50mm lenses) and with Cartier-Bresson’s “decisive moment” in mind. Singh put his own spin on Cartier-Bresson’s philosophy of spontaneity: “In India, I am on court … the tennis player’s court, where the ball has to be hit to the edge of the camera frame, so that it raises dust, but yet, it is inside.”

By the mid-1970s, Singh sometimes even seemed to be borrowing from Cartier-Bresson: Singh’s 1976 color photograph of villagers peering into a circus tent, as Fineman observes, echoes Cartier-Bresson’s Brussels, Belgium (1932), of a man peering into a burlap tent. But once again, it was rejection that pushed Singh forward. In 1977, when he was working on a book about Paris for Time-Life Books, he visited Cartier-Bresson at his apartment and brought along his first two books, Ganga: Sacred River of India and Calcutta. Cartier-Bresson, who was known almost as much for his horror of color photography as for his “decisive moment” approach, barely looked at the books, flipping a few pages before decisively pushing them aside. It was the brush off that Singh needed to strike out on his own.

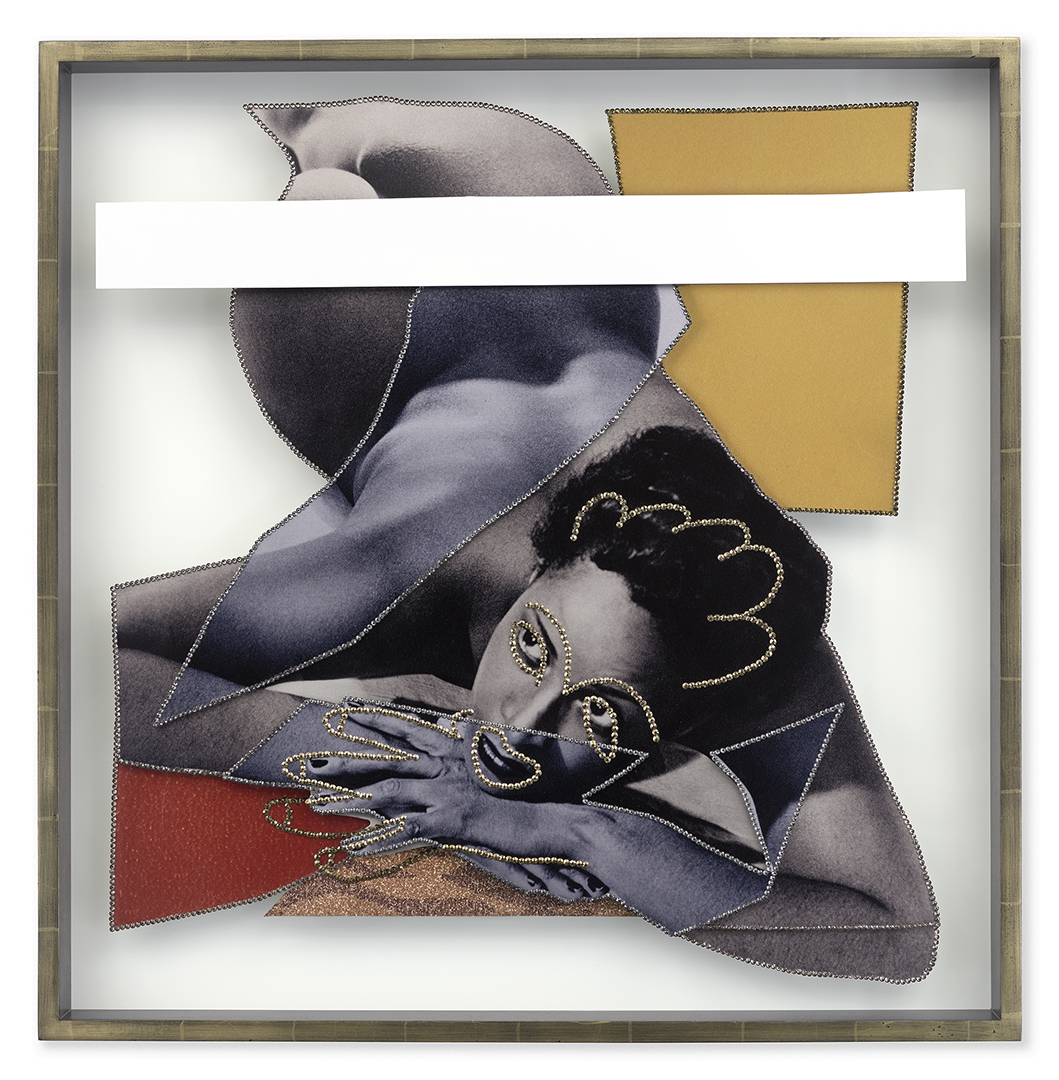

Singh began to realize that color was “part of a continuous Indian aesthetic tradition that reached back to the vibrantly colored court paintings of the Mughal period,” Fineman writes. He also began, in contrast to Cartier-Bresson, to develop “a vision that was inherently capacious and untidy,” to make photographs that “are multiepisodic and give the impression that life continues beyond the edges of the frame.” What came to distinguish Singh from other photographers was “the knowledge that one cannot isolate the decisive moment; that the spectacular, especially in India, happens in the context of the everyday,” as the journalist Shoma Chaudhury puts it in the catalogue.

Color, Singh explained in his introduction to River of Colour, was as integral to the fabric of India as black-and-white photography was to the Western world: “The fundamental condition of the West is one of guilt, linked to death – from which black is inseparable. The fundamental condition of India, however, is the cycle of rebirth, in which colour is not just an essential element but also a deep inner source.” Color is inseparable from India. “Those delicious notes,” he added, “those high and low notes, they do not exist in the Western world.”

Singh found ways to bring out those notes and amplify their joyous cacophony – by using a flash in broad daylight and by welcoming mirrors, veils, windows, display cases, statues, animals, shadows, bodiless hands, and bodiless heads into his frame. Such elements make for photographs that are so chaotic, so decentered, that it’s hard to know where to look. You want to look everywhere; that’s part of the fun. Which reminds me of yet one more rejection – this one not of Singh but by Singh.

A lot of Western photography, especially black-and-white photography, is pretty sober, even somber (Helen Levitt and a few others excepted). Many of Singh’s pictures, I think, are frankly funny, especially some of the pictures he took at the end of his life. One of his last series, for instance, involved the Ambassador, India’s national car. In these pictures, the car is a character, a framing device, a stage, a place of reflections, and a beloved and dumpy figure of fun.

When Singh died he left a number of unfinished projects. One was about icons – both civic statues and Hindu sacred images. In this project, writes Mitter in the catalogue, Singh “took his cue from the great writer R. K. Narayan, who wrote, ‘I find statues in general rather comical. There is something ludicrous in stationing a figure permanently in the open … in a frozen attitude of benevolence, heroism, or contemplation.’”

Perhaps it was that spirit of mockery, only turned on himself, that drove Singh’s last project, which ended when he died, unexpectedly, of a heart attack in April 1999. This was a series of “selfies” (before they were called that) made by holding the camera at arm’s length. Although Singh was surely acquainted with Eugène Atget’s occasional reflection in the window of a building, and Lee Friedlander’s forlorn practice of including a bit of himself (sometimes just a shadow), Singh made the tradition his own by casting off its somberness. He made it funny. In one photograph taken in New York’s Union Square, a part of Singh’s round mug invades the frame, which also contains a statue of Gandhi. The title of the posthumous book was Mischief – not a bad epitaph for a man whose great subject was the unruliness of life beyond the frame.