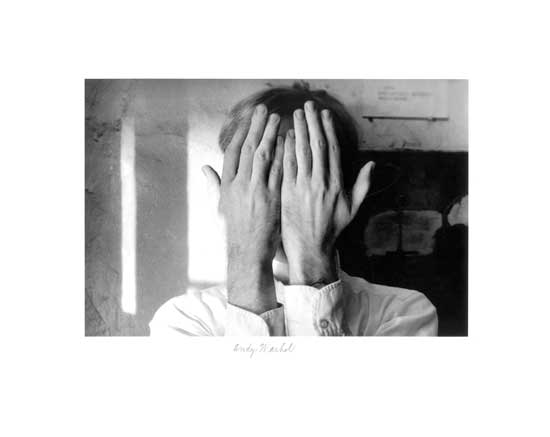

In late September, I interviewed the cantankerous photographer Duane Michals, now 87, who is known for composing photographic dramas that often include his handwritten text. Over the phone we talked about many people and things, about Robert Frank (whom he loves) and Allen Ginsberg (loathes), Giorgio de Chirico (loves), John Szarkowski (loathes), authenticity (loves), religion (loathes), Saul Steinberg (loves) the art world (loathes), Balthus (loves).

The occasion for our conversation was Illusions of the Photographer: Duane Michals at the Morgan Library & Museum, Michals’s first New York retrospective, on view through February 2, 2020. (The Duane Michals Show was at the International Center for Photography in 1992, though it had been organized by the Museum of Photographic Arts in San Diego.) A smaller show of Michals’s work, Mischievous Eye, opened at D.C. Moore Gallery in New York on November 14. The exhibition, organized by the Morgan’s curator Joel Smith, comprises six decades of Michals’s fictional photographs and sequences of photographs, which are paired with objects from the Morgan’s collections that Michals chose, including Embrace, an Egon Schiele drawing; Saul Steinberg’s sketch of a calendar wheel following a cat; a double exposure of a children’s tea party; and a freakish double portrait of Jack Dempsey and Babe Ruth that makes them look like conjoined twins.

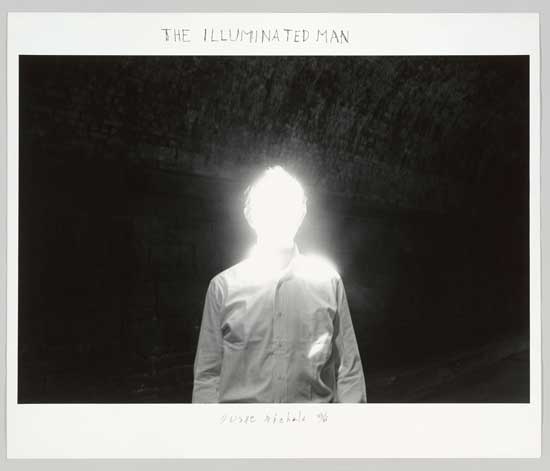

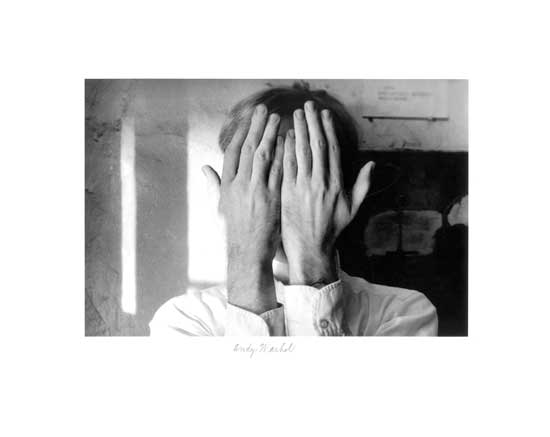

This exhibition of odd pairings is perfect for Michals, because he is all about pairs and pairing. His photographs often feature couples. And even when there is only one subject, that solitary person is often haunted by the ghost of someone, or by the memory of someone, or by an implied voyeur, or by a surprising text. “When I write, it’s to talk about what you cannot see in the photograph,” he told Smith.

Why does Michals favor pairs over singularities? He responded tartly: “One is masturbation. Two is interaction.” In other words, he prefers drama over diddling: “I’m a storyteller.”

In fact, Michals is bubbling over with stories. He told me one about the street photographer Garry Winogrand, who looked over one of Michals’s sequences in 1963 and declared: “This isn’t photography.” Michals seemed proud of that dis. The only game in photography back then, he said, was street photography, and while Michals admires Henri Cartier-Bresson and Robert Frank, their approach just doesn’t work for him. He doesn’t do the decisive moment, he said, “but the moment before the decisive moment and the one after it.”

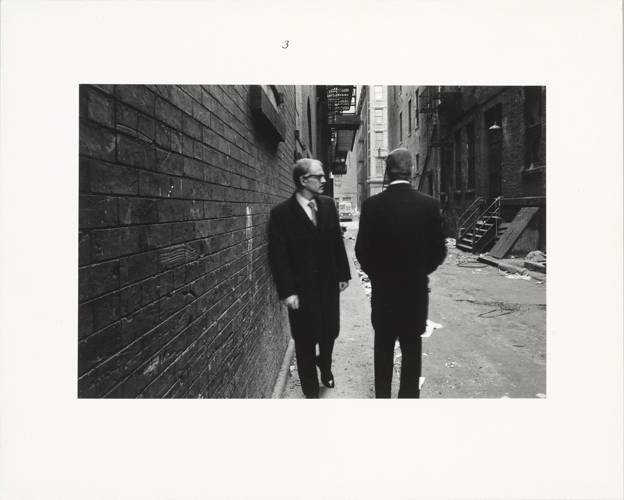

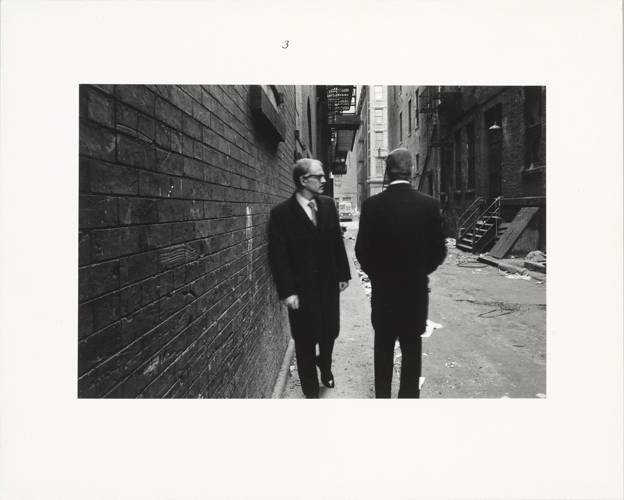

Consider the six-frame sequence titled Chance Meeting, 1970. Two men walk in opposite directions and pass one another on a narrow sidewalk littered with paper. As they pass, the one walking toward us, who’s wearing glasses, turns slightly to get a glimpse of the younger man. Once they have passed one another, the man in glasses, close to us now, turns completely around, but by this point the younger man is far away with his back turned. Once the glasses man is out of our field of vision, having walked beyond us, the younger man turns completely around to see the older man, whom we cannot see anymore. It’s like an O. Henry story. They are curious about one another, curious enough to turn 180 degrees and stare, and yet blind to each other’s curiosity – ships passing and almost docking, but not. (Although Michals is gay, he said it never occurred to him that Chance Meeting would be read as a cruising narrative.)

Michals has always made his living as a commercial photographer (which he loves). As he noted in the catalogue: “I was thrilled to do a campaign for MassMutual, or a Life magazine cover, or the Paris collections for Vogue.” And sometimes he has used his commercial techniques to create his fictional photographs. He did not just happen upon Chance Meeting, for instance. He knew the men, and he scouted for a street and sidewalk narrow enough to make a dramatic encounter.

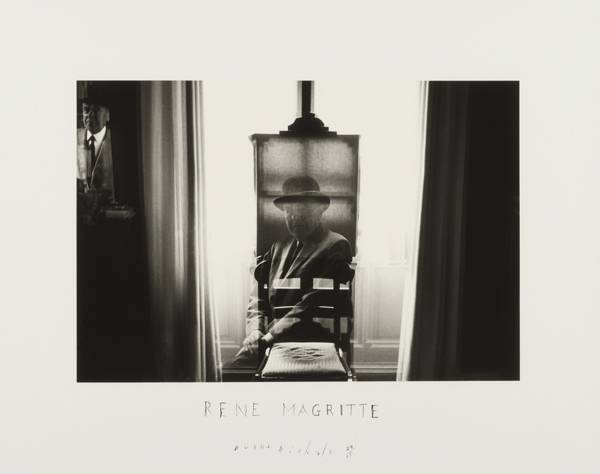

“It’s not reportage,” he said to me. It’s not street photography; it’s not the art of shooting what actually is, which he said he finds pointless. As he noted in the catalogue, he often tells his students, “I know what snow looks like. Show me what I don’t know and what only you can give me.” That’s why René Magritte is one of his heroes. (Michals’s René Magritte at his Easel, 1965, is included in the show.) What Magritte paints can look realistic, factual, but it contradicts what we know.

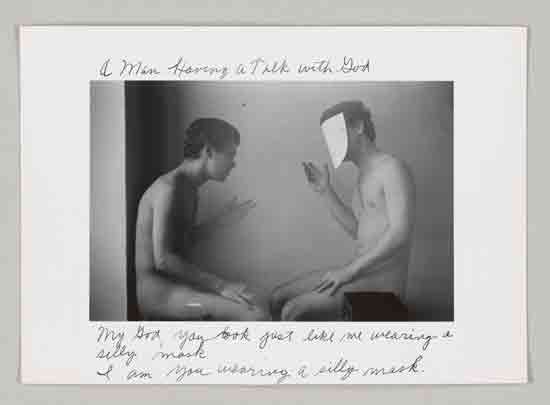

This is also what Michals does. He creates fiction with his photographs. Another of his sequences stars two naked men sitting knee to knee; they’re comfortable, gesturing. One of them is in a paper mask that could’ve been made by Saul Steinberg. The sequence is titled A Man Having a Talk With God, 1975. What they say to each other is written in casual cursive underneath. The man on the left says to the man in the mask (God), “My God, you look like you’re wearing a silly mask.” And God says, “I am you wearing a silly mask.” The man responds, “If that’s true, why don’t I know it?” And God answers: “You choose not to know it.” The dialogue goes on for a couple more frames, then ends abruptly: “I don’t understand any of this.” God gets the last word: “It doesn’t matter.”

Given that many of his sequences have a mystical aspect, you might think that Michals, who was raised Catholic and seems obsessed with death, respects the theater of the church. Not so. When I asked him whether he got his sense of drama from Catholicism, he demurred, colorfully: “You know how when you have a glass of wine and you spill it on your best shirt? Well, that’s how it is. I’ve been stained by the Catholic Church.” It’s very hard to wash out. “There is no god,” he adds. “It’s so stupid.”

Michals does, however, have a religion: authenticity, which is not the same as factual truth and not the opposite of fiction. In fact, authenticity seems to be Michals’s prime value in his fictional photography. This led me to bring up Gregory Crewdson, who also does fictional photography; Allen Ginsberg, who, like Michals, wrote on his photos; and Cindy Sherman, whose self-portraits are fictions. Michals was appalled at my comparisons.

Near the end of our conversation, I asked Michals to talk about one of the objects from the Morgan that he selected for the show. He chose Voltaire’s briefcase, a reddish leather envelope with gold print embossed on it – Portefeuille de Monsieur de Voltaire. Michals said he finds it thrilling because he imagines Voltaire toting the briefcase from Paris to Geneva: “He’s sitting in a carriage with the briefcase, and he’s got his hand on the leg of a woman next to him, and the briefcase is bouncing because he’s got an erection.”

Not everything is fun and frolic with Michals, though. The saddest pairing of the Morgan exhibition is two letters. One is Hartley Coleridge’s letter to Sara Fricker Coleridge, written on May 2, around 1828. Hartley has so much to say that his letter is written in both a horizontal and vertical orientation, which makes a fine and beautiful weave. Michals paired it with A Letter from My Father – a 1960 portrait of Michals’s father (frowning, hands on hips), his brother (sullen, in profile), and his mother (recessive, worried) – under which he wrote a bitter script in 1975: “As long as I can remember, my father always said to me that he would write me a very special letter … I used to try to guess what secret would be revealed, what mystery and intimacy we would at last share … But then he died and the letter never did arrive. And I never did find that place where he had hidden his love.”

Before we hung up the phone, Michals had one more thing to transmit to me, “I am a bad boy.” It was important that I know this.