The initial impression of a hodgepodge of artifacts in Nina Katchadourian’s exhibition Uncommon Denominator, on view through May 28, slowly coalesces into a story of sorts – a story of the artist’s diverse interests and experiences, but also a story of us. Katchadourian was invited to mine the collection of the Morgan Library, selecting objects, artworks, and books that provide the armature for this wunderkammer of a show. In what she calls show-and-tell conversations, she also asked staff members to tell her about pieces in the collection they’d like to see exhibited, a number of which are included. Those objects are interspersed with Katchadourian’s own artwork and personal items from her family history, arranged in vignettes and accompanied by explanatory wall labels.

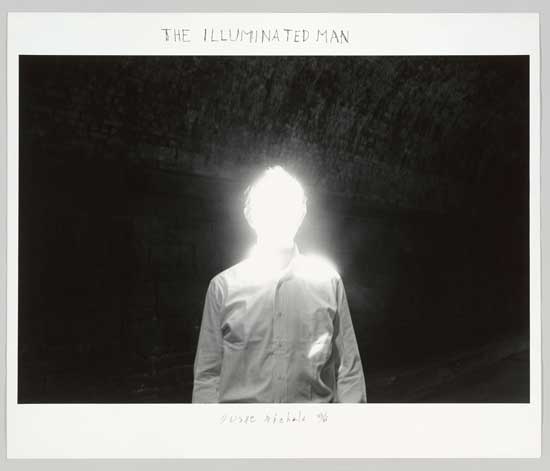

The exhibition rewards close looking. Perusing the objects becomes something of a sleuthing game, as if deciphering the secrets of the Illuminati – not a far-fetched notion while visiting the former home of a robber baron. Sometimes the connections are purely visual, as with a trio of cameraless abstract photographs; sometimes they’re related by subject, as with Katchadourian’s photograph of a globe paired with a portable, collapsible fabric globe from the 19th century. In an interview with curator Joel Smith in the catalogue, Katchadourian says that a featured drawing by Saul Steinberg sums up how the exhibition works: it depicts a man looking at a painting in the lower left corner, and a thought bubble that fills the entire page with his meandering chain of associations.

The show also provides a touching look at how Katchadourian’s family origins have shaped her as an artist – her mother is Finnish, her father Armenian, she grew up in California. She says her grandparents are as important to her personal aesthetic as the artists she studied in graduate school. Among the cherished items she included in the show is an embroidery sampler made by a “bonus” grandmother, a woman who was orphaned by the Armenian genocide and eventually adopted by the artist’s father’s family in Lebanon. Orphan girls were taught skills like embroidery to improve their chances of being adopted. In the context of this show, the sampler’s stitches suggest a diary page or encoded memories.

The most endearing work in the show is a hand-made, accordion-folded photo album compiled by her Finnish grandmother, who photographed Katchadourian’s mother in the same nightgown on every birthday from the age of three, when the garment covers her whole body, to 14, when it’s more of a mini-dress. Hanging above the vitrine is a work by Katchadourian comprising cut-outs of Lake Michigan from variously sized maps, arranged from smallest to largest, as if growing like her mother. In format, the album draws an unavoidable comparison to Ed Ruscha’s accordion-fold photo books. In subject, it finds kinship in the works of Nancy Floyd, who has photographed herself daily for 40 years for her project Weathering Time. Yet for Katchdourian’s grandmother, the album was a loving memento that she eventually presented to her grown daughter, bound and titled The story of why Stina’s nightgown became too small.

A nautical-themed display features a model ship and the fragment of a champagne bottle that was used to christen J.P. Morgan’s yacht, which tie in to Katchdourian’s work based on a 1973 book, Survive the Savage Sea, that profoundly affected her as a child. It tells the true story of the Robertson family and the harrowing measures they took to stay alive after their boat was destroyed by an orca pod, setting them adrift in the Pacific Ocean for 38 days. Katchdourian gathered every translation and every edition of the book and lined them up on a shelf, using the cover illustrations to sequence them from departure to rescue. On the wall below is a related black-and-white photo, We Saw Ourselves in Your Rescue Photo (2020), which pairs similarly composed, roughly concurrent images of the Robertsons being rescued in their dinghy and the Katchadourians on a family outing in a small boat.

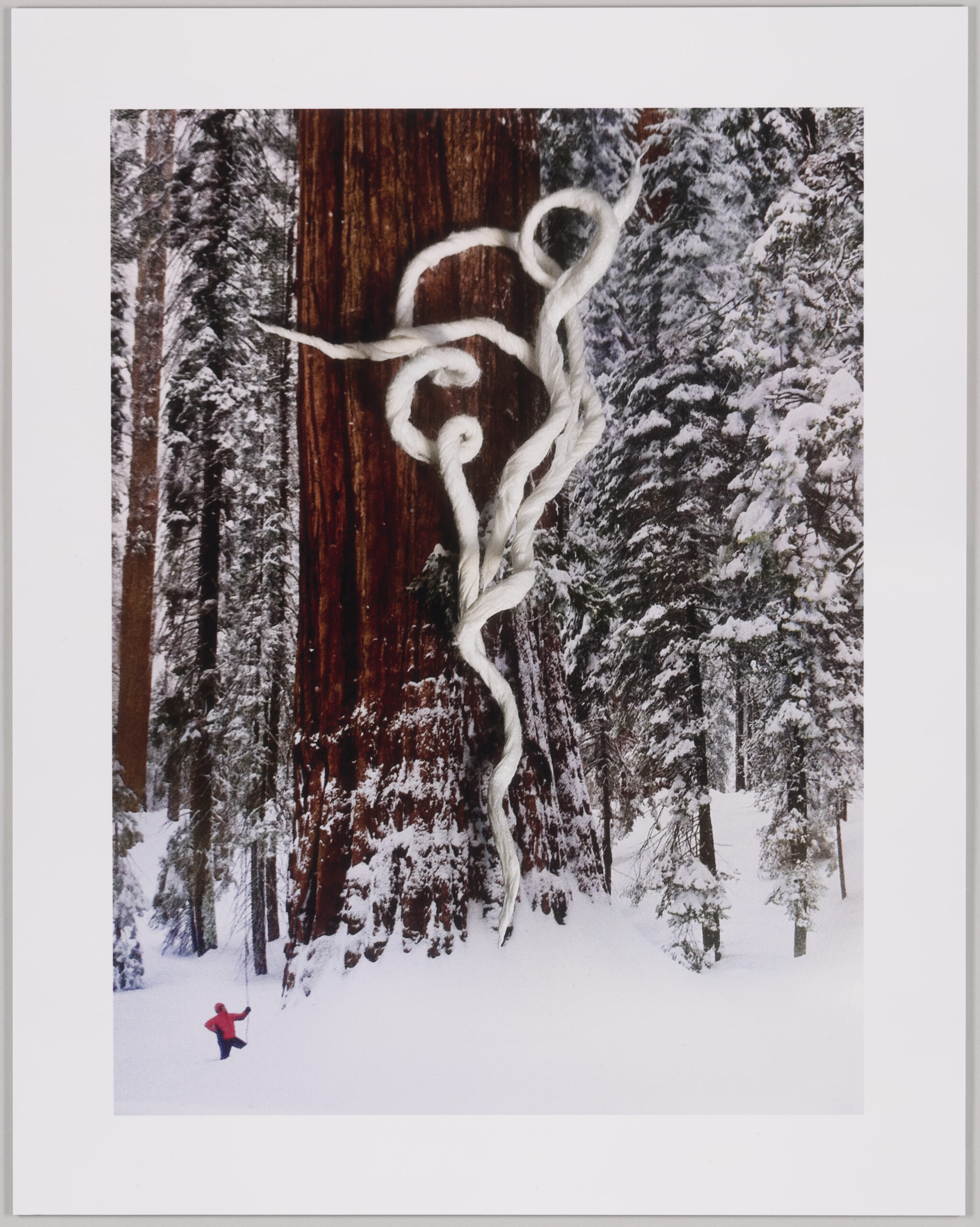

Katchadourian’s penchant for organization and repairing comes from her maternal grandfather, whose detailed backyard-bird nesting chart is on view here, as well as his artfully repaired plastic storage box lid, its shattered pieces held together with wood, screws, and oozing paint, an abstraction that the artist displays in her home like a painting. The lid accompanies a 1998 photo of mushrooms in a forest with brightly colored polka dots that are Katchadourian’s attempt to “repair” the torn mushrooms – like her Mended Spiderweb series of the same year, an exercise in whimsical futility. The dots are made from bicycle-tube patches she found in her grandfather’s meticulously organized tool shed after he died.

For her ongoing series Sorted Books, begun in 1993, she has selected books from private or institutional collections and arranged them so that the titles on their spines create short phrases. Here, for example, Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? sits atop books with the titles Don, Joey, Charlie, Elmer, Ferdinand, and Tiny Alice. Though a collectors’ favorite, it’s a series that perhaps, like family portraits, only the books’ owners would hold dear.

Uncommon Denominator could also be seen as an attempt to make sense of the stuff we cling to, even if it clutters our garages, attics, and lives. But in Katchdourian’s world, objects are imbued with meaning, cast-offs have value, and all things are connected.

Stephanie Cash is an editor and writer based in New York.