Isaac Julien is not a photographer in the traditional sense, but his work is steeped in the history of photography. He contests and reinterprets various artistic mediums, most notably film, in works that incorporate and reimagine the still image. Through an amalgamation of symbolic montages, short film sequences tell a story about the subjects of his work, most recently the abolitionist and statesman Frederick Douglass. The London-born filmmaker and installation artist rose to prominence after releasing the critically acclaimed 1989 drama-documentary Looking for Langston, in which scripted scenes and archival imagery establish a non-linear plot that memorializes the Harlem Renaissance and the prolific African-American activist and poet, Langston Hughes. Garnering a cult-like following early in his career, Julien has become known for such experimental inquiries.

His most recent multi-screen film installation, Lessons of the Hour, which premiered at the Memorial Art Gallery at the University of Rochester in 2019, is on view, for the first time since its debut, in I Am Seen…Therefore, I Am: Isaac Julien and Frederick Douglass at the Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art through September 24. Julien’s research into Douglass’s writings and speeches forms the backdrop of the exhibition, which marks the 180th anniversary of Douglass’s first visit to Hartford in May 1843 and explores his reflections on race, citizenship, and the power of images. Curated by Harvard University colleagues Sarah Lewis and Henry Louis Gates, Jr., scholars of African-American history who have both become critical voices in our understanding of race relations in the U.S., the exhibition also brings together more than 100 rare 19th-century daguerreotypes of anonymous African Americans from the 1840s and ‘50s, on view here for the first time. The exhibition includes daguerreotypes from Black-owned studios like Augustus Washington’s in Hartford and James Presley Ball’s in Cincinnati, as well as from anonymous studios from around the country. The names of nearly all the sitters are unknown, waiting to be discovered by descendants or academics researching archives. “Here we have this contemporary figure, the extraordinary Sir Isaac Julian,” says Lewis, “and we have this historic focus not just on Frederick Douglass and the ephemera associated with his speeches … but also this suite of over 100 daguerreotypes of anonymous Black Americans from the 1840s and 1850s. And so we have this synoptic sweep from this historical period to the current day.”

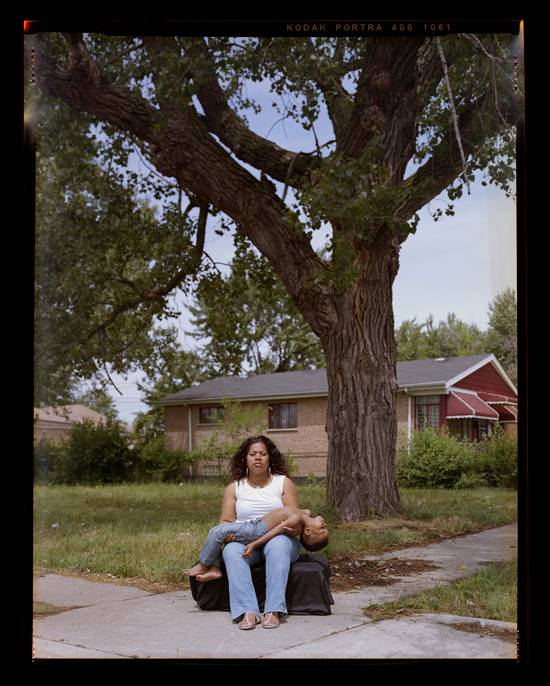

Installed over five screens at the Wadsworth, Lessons of the Hour depicts reenactments of the life of Frederick Douglass interspersed with surveillance footage from the 2015 riots following the death of Freddie Gray. Gray, 25 at the time of his death, was arrested one morning in Baltimore, put in the back of a transport van and, less than an hour after making contact with police officers, he was found unconscious, his spinal cord nearly severed. Gray was transported to a nearby hospital, in a coma, and died several days later. His death sparked a national outcry and led to nearly 20 straight days of marches and rioting in Baltimore. Blending the past with the present throughout the film, Julien examines the underpinnings of race relations from the era of Douglass to the present day to encourage spectators to engage with our marred history while contending with the violent present. His use of multiple screens of varying sizes combining scripted scenes with archival imagery and sound pieces breaks from the conventions of filmmaking and film viewing.

The Memorial Art Gallery commissioned Julien to produce a work related to the city of Rochester in 2016, and he became interested in Douglass after seeing a monumental bronze statue of the author and abolitionist in Rochester. Douglass lived in the city from 1847 to 1872, publishing newspapers and helping people fleeing along the underground railroad, and several statues around the city commemorate his life and work. (One of them was vandalized in 2020.) The most photographed man in the 19th century and one of America’s most important historical and political figures, Douglass used images to challenge slavery and racist depictions. “Douglass was arguing that the stereotypes that were denigrating African Americans could be reversed through this dignified presentation in front of the camera, through representation itself,” said Lewis. “What is the relationship between visual representation, the right to be seen, and a representational democracy? That’s really the central question of the show.”

For 40 years, Julien has bent, stretched, and expanded the traditions of cinema to include multi-layered visual and sonic experiences. His film Ten Thousand Waves, 2010, for example, exhibited in the Marron Atrium at MoMA in 2013, was projected on nine double-sided screens installed at multiple heights, and he worked with sound designers to ensure that the audio quality of the film could be fully realized in the cavernous space. The film, which was inspired by the Morecambe Bay tragedy of 2004, in which more than 20 Chinese cockle pickers drowned off the coast of England, is among seven films on view at the Tate Britain in London through August 20 in the retrospective Isaac Julien: What Freedom Is to Me, films that engage in some of the most critical social and political issues of our time. A photographic series based on the installation at the Tate, Once Again… (Statues Never Die), is on view at Jessica Silverman in San Francisco through July 22. “The question of freedom isn’t just connected to questions of rights and justice, it’s connected to what stories you want to tell, and how they’re told,” Julien said in a recent interview with the New York Times. Black artists have historically been marginalized in the art world, and Julien, co-founder of the Sankofa Film and Video Collective, understands the importance of autonomy over the creative process. Refusing to be constrained by convention, his works, which encompass video, sound pieces, moving images, and photography, breathe life into critical issues of the human experience regarding race, gender, and sexuality. “My hope,” says Lewis, “is that visitors to the show leave with a deep sense of their place in this larger legacy and history, inspired to see the role they can play in this relationship between race, art, and justice in the United States.”