Every photographic frame implies a framer, a view finder at the viewfinder. The camera has an operator, it is assumed, even if their presence remains implicit. In her work from the past three decades, Christina Fernandez has often made her physical position explicit, by shooting through windows and doors and including those architectural frameworks within the bounds of the photograph. Given her ongoing focus on labor, migration, identity, and Latinx Los Angeles, this formal strategy readily extrapolates into metaphor and politics, subtly prompting such questions as: What social forces are at play here? How does this image perpetuate or disrupt assumptions? Who stands outside of the pictured realm, and whose habitat lies within? What is the power dynamic between insider and outsider? The frame reads anew as the delineation of a scope of understanding, and not just the artist’s, but our own. At once, the frame announces and challenges the limits of what we see and know.

The “staging of vision and the ethics of looking” are at the core of Fernandez’s work, writes Roberto Tejada in the fine catalogue accompanying the artist’s first museum survey exhibition, Christina Fernandez: Multiple Exposures. The show, organized by California Museum of Photography (CMP) senior curator Joanna Szupinska, is on view at the CMP through February 5, 2023, and will travel nationally through 2025.

Born in 1965 in Los Angeles, where she still lives and works, Fernandez bears the same educational resume that has served many of her peers as an on-ramp to wide recognition: undergraduate degree from UCLA (where Joyce Niemanas and Chris Burden were influential), and MFA from the California Institute of the Arts (where studying with Allan Sekula was the draw). Her exhibition history, beyond a steady run of solo presentations in Southern California, has been weighted toward shows themed around Chicano identity and the art of California, both of which are essential foundations of her work. The CMP exhibition, and particularly the book, with its intentionally large number of contributors, promise to situate Fernandez more broadly within lineages of New Topographics and staged and narrative photography. “My identification as a Chicana is very solid and I’m comfortable with that,” she says. “It’s an appropriate term for me and my work.” Multiple Exposures will certainly expand our understanding of Fernandez’s motivations and approaches. “Maybe,” she adds, “it can also expand what we think of as Chicano art.”

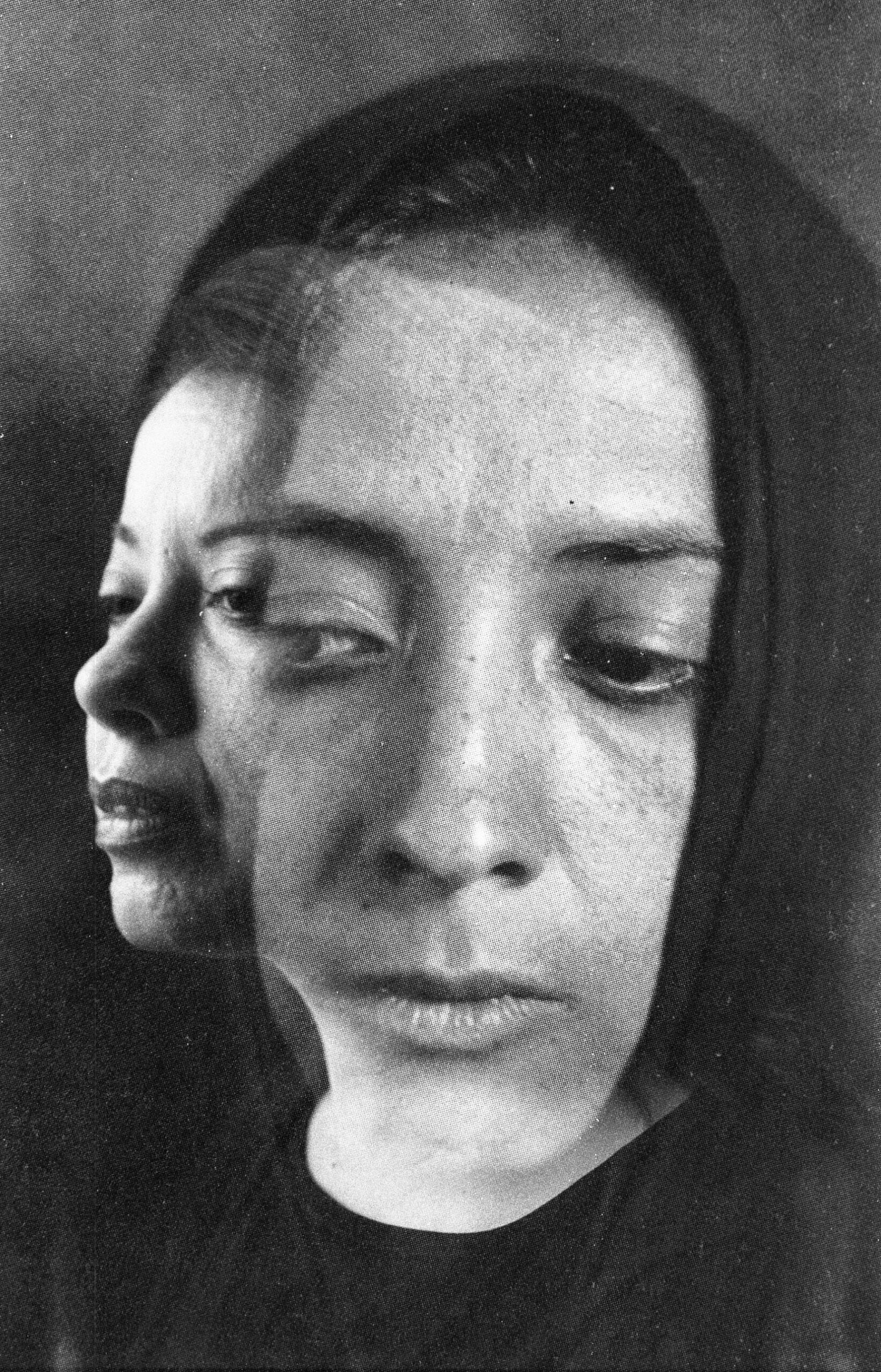

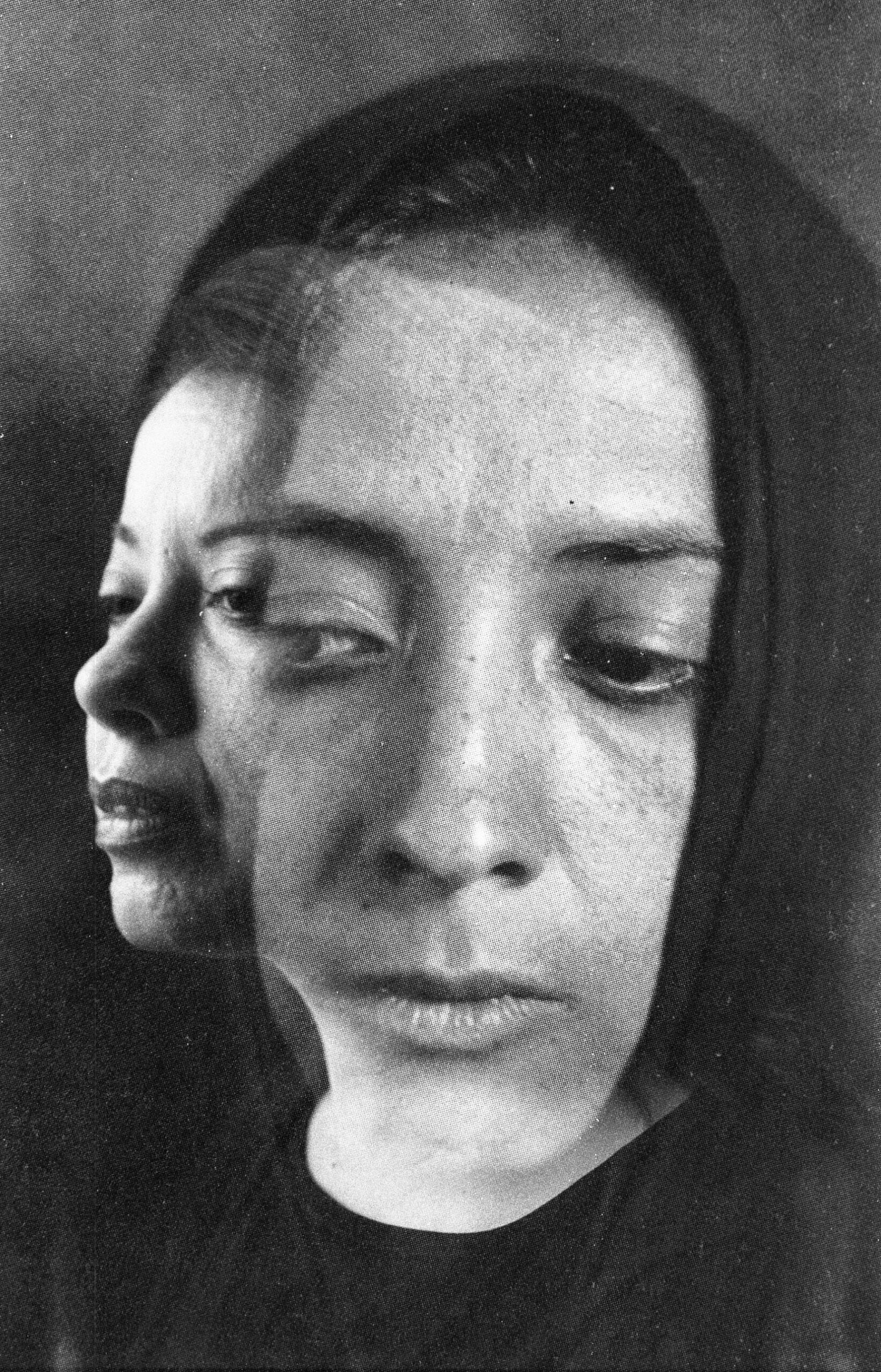

Christina Fernandez, Untitled Multiple Exposure #8 (Modotti), 1999. Courtesy the artist and Gallery Luisotti

The show takes its title from a 1999 series of eight images that layer Fernandez’s self-portraits with appropriated reproductions of photographs of indigenous women in Mexico by Tina Modotti, Nacho López, Manuel Álvarez Bravo, and Gabriel Figueroa. In Untitled Multiple Exposure #3 (López), Fernandez assumes a standing pose echoing that of the subject’s in the earlier picture by Lopez. The portraits merge but imperfectly; they are slightly offset, like a visual stutter. The arms of López’s subject gently join in front of her body and seem to also wrap around Fernandez, suggesting kinship within distinctness, connection simultaneous with difference.

Issues of inheritance and ancestry also drove Fernandez’s earlier, stirring project, María’s Great Expedition (1995-96), in which she re-enacted her great-grandmother’s journey from Mexico into and through the American southwest via photographs, text, and a map. In its form and feminist bent, the piece brings to mind Eleanor Antin’s performative practice of inhabiting both fictional and historical figures. Fernandez’s piece reads as both an homage to her great-grandmother’s fortitude and a critique of traditional historical narratives that exclude such stories of female-centered, domestic-scaled acts of courage in favor of charting and lionizing male, imperialist ambition.

Attention to labor, particularly underrecognized labor, pervades two other significant bodies of work, in which Fernandez put visual emphasis on the particularities and implications of place. In a 2002-03 group of color, nighttime views into laundromats in Latinx-dominated east L.A., Fernandez uses the doorways and panes of the glass facades to neatly structure her compositions, while the graffiti etched upon those surfaces and the blurred contours of the activity within impose a charged distance between outside observer and interior reality, between speculation and experience.

That division is even more pronounced in Manuela S-T-I-T-C-H-E-D (1996-2000), a sequence of frontal views of the exteriors of small garment factories, their doors padlocked and windows barred. The series owes much to the vision of Lewis Baltz, whose cool stance Fernandez adapts, while adding her own brand of narrative heat through an introductory panel of embroidered text that evokes one woman’s fear after a worksite raid by la migra. Fernandez excels at invoking complex historical and societal issues through attention to individuals, however abstracted or abbreviated their stories. She does this relatively quietly in the most recent series in the exhibition, View From Here (2017-19), by foregrounding the textures and dimensions of private portals through which other artists have regarded their surrounding landscapes – Laura Aguilar’s garden-view window with stones on the sill, for instance, or Noah Purifoy’s doorframe whose mix of materials qualifies it as an assemblage in itself.

That continuity between the personal and the political resonates forcefully in a sculptural installation Fernandez first made as an undergraduate and remade as a photo-piece at CalArts. Untitled Farmworkers (1989/2020) is featured in Christina Fernandez: Under the Sun, at the Benton Museum of Art at Pomona College, one of two companion shows to Multiple Exposures. (The other, Tierra Entre Medio, at UCR Arts, adjacent to CMP, brings new work by Fernandez together with work by three younger Chicanx photographers – Arlene Mejorado, Lizette Olivas, and Aydinaneth Ortiz – she selected for their shared, intersecting interests in place, personhood, memory, family, and belonging.)

In the reprised installation, white cards with text identifying specific farmworkers and the mode of injustice they suffered (work injuries, toxic exposures, death) are planted in rows, like seeds, or headstones, in a bed of soil on the floor. The photographic version is comprised of a grid of images, each showing a hand setting a card in the dirt. It has an arresting formal rhythm, amounting to a relentless beat on the conscience. The photo piece Fernandez made in graduate school made her fellow grad students uncomfortable, she remembers. “They questioned the validity and truthfulness of the information, which was upsetting, but when you accept the information, you have to accept something about yourself, and how you’re positioned, and that’s the hardest thing for people. You’re either complicit in the system and continue to live the way you live, or you’re challenged to do something about it, to become a participant and try to figure out a solution.”

Leah Ollman writes for the Los Angeles Times, Art in America, and other publications. She has contributed to books and exhibition catalogues on artists including Betye Saar, Julie Blackmon, Michael Light, Alison Rossiter, Michal Chelbin, William Kentridge, and Christine Corday.