Ralph Eugene Meatyard was born in Normal, Illinois, a delightful biographical fluke, since his the man himself was anything but ordinary: he was an optician who made intentionally blurry photographs and a family man who made unsettling and deeply strange pictures of his family and friends. He was also a profoundly influential photographer: we are so accustomed to seeing certain aspects of his work in contemporary imagery – blurred, haunted figures and staged fictions involving masks, dolls, and other props that show up in the work of photographers from Francesca Woodman and Roger Ballen to Gerald Slota – that it’s easy to forget how unorthodox they were in the 1960s.

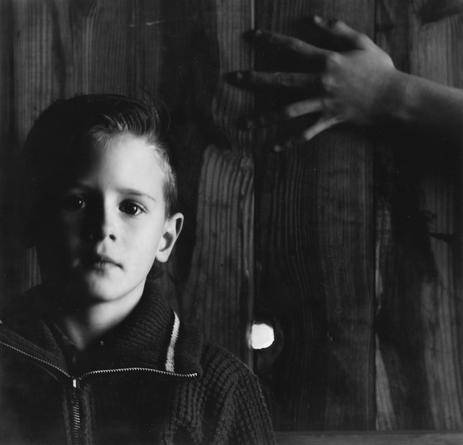

A full-time optician, Meatyard made images in his off hours. Though he called himself (proudly) an amateur, he was enmeshed in the arts community of Lexington, Kentucky, which included the writer Wendell Berry and the Trappist monk and poet Thomas Merton. There is a dark, Southern Gothic quality to some of his work, including pictures of his children in abandoned barns and houses in and around Lexington. In one on view here, a young boy stands next to a partly open doorway, unaware of the shadowy figure emerging from out of the darkness next to him. In another, a boy stands against a barn wall, gazing into the camera, and a disembodied hand reaches into the frame just behind him. The composition is perfected by a bright hole in the wall near the boy’s shoulder.

Meatyard’s take on childhood – also reflected in much contemporary photography – was utterly unsentimental. In his photographs, his children are unsupervised, and their games and explorations seem purely their own inventions: funny, scary, strange, and melancholy all at once.

Also included in this generous show of 40 photographs, on view at DC Moore Gallery through December 23, are images from Meatyard’s series Motion-Sound and Zen, in which he often used an unlikely practice that he called “no focus,” jiggling the camera as he took pictures of trees or a barn, or a single twig, producing blurred images alluded to dreams or visions. Uninterested in using the camera to record facts, Meatyard preferred to evoke, as he put it, “the feeling of being not quite of this world.”