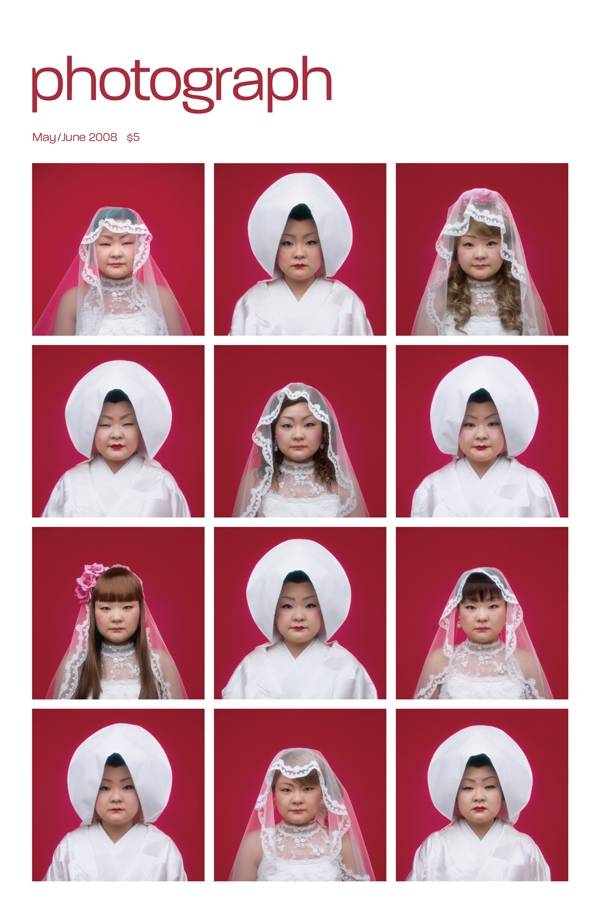

When Carleton Watkins made his photographs of gravel quarries, mining operations, and sawmills in the 1860s, America was a larger place, and these interruptions of a previously pristine nature were confirming signs of a great errand into the wilderness. When photographer David Maisel flew over Mt. St Helens in 1983, several years after its eruption, with his teacher Emmet Gowin, he must have felt Watkins’ awe in the face of nature’s shaping power. But the sense of celebration soon yielded to horror, fascination, and fear. The more time Maisel spent aloft, the more his view revealed that what seemed to be the signs of successful enterprise had become vast scars, of open-pit mines, polluted lakes, and military test sites. Maisel set out to document this manmade devastation from the air in a decades-long project he calls Black Maps. Maisel is among a group of American photographers—including Edward Burtynsky and Richard Misrach—who have made their art careers out of environmental catastrophe. They are the “new topographers” of a refuse-strewn, mephitic Earth. Maisel’s most recent flyby shooting examines Utah’s Great Salt Lake, a forbidding natural wonder that is also under environmental pressure. Blooms of algae are beginning to appear on the lake, and mercury levels are rising. On view at Paul Kopeikin Gallery in Los Angeles (May 7–July 7) and Cheryl Haines Gallery in San Francisco (June 9–July 16), the series Terminal Mirage, from which our cover is drawn, is as visually mesmerizing as an abstract canvas, with its sharp geometries and green florescence. The end of the world surely never looked this good. So good, in fact, that it is often difficult to know what we are seeing. For Kopeikin, that paradox supplies the images’ power. “These pictures don’t resolve themselves into simple statements of good versus bad,” he says. “You have to deal with the beauty of them even when you know what they depict.” Maisel himself has emphasized the psychological over the documentary nature of his project, calling his landscapes “an archetypal space of destruction and ruin that mirrors the darker corners of our consciousness.” Extended without limit, the very things that hypnotize us with the aesthetic dimension of humankind’s presence—our architecture, our machines, our domestication of wilderness—contain the seeds of our destruction, modernity’s poisoned wish. Perhaps when all the warnings have become laments, the last photographer will record the singularly beautiful image of a worn-out world, terminal but no longer just a mirage. If so, then we will have re-enacted a story much older than that of Watkins or photography—the story of Narcissus, who falls in love with his own reflection, pines away and dies.