Ken Josephson has been called an early and influential conceptual photographer, but it might be more accurate to say that he has always been fascinated by photography’s odd combination of illusion and truth. A mini retrospective, on view at the Denver Art Museum (through May 8), and a new book, The Light of Coincidence (University of Texas Press) offer opportunities to consider again his witty and precise vision.

Lyle Rexer: You didn’t set out to become an art photographer.

Ken Josephson: Not at all. I wanted to be a commercial photographer. I had been a darkroom slave for General Motors and heard about the Rochester Institute of Technology, so I went there to learn skills. But it turned out to be very science based. Nevertheless, the charismatic Ralph Hattersley was there, and Beaumont Newhall, with whom I learned photo history. In my final year, Minor White arrived. He taught us to really appreciate photographs by looking long and hard at them. He also insisted on the zone system for black-and-white photography, which I hated. I said, if I have to master this I’ll never get anything done. One thing Minor did do was to steer me to the Institute of Design for graduate study, where I went on the G.I. Bill.

LR: The Institute of Design has become legendary. Founded by Moholy-Nagy as an offshoot of the Bauhaus Institute, its graduates have included such talented and innovative photographers as Ray Metzker, Barbara Crane, Judith Joy Ross and Art Sinsabaugh. What was it like when you were there?

KJ: I was blessed to be there. Harry Callahan and Aaron Siskind were teaching, and together they taught me to be professional. They emphasized exploiting the qualities of the medium, and that the specific means don’t matter: if something works to get your ideas across, whatever it is, use it. But to give you a better idea, when I taught for a semester, one of the students lit a piece of photo paper on fire, for the exposure light, then put it in the developer. I was astounded, but that was the environment. It was really refreshing. But all my experimenting was done in the camera. For me it was a framework, a visual boundary. I also learned that at its most basic level, photography is a form of mark making.

LR: I can see that in some of your street photographs, where light is used to spot people and places. One of my favorites is taken under the El in Chicago, where each person standing on the curb is marked by light.

KJ: Light is so important in my work; I use it to express ideas and convey the sense of time. The photograph you mention happened because I noticed that the people on the curb were picked out by the fragmented light falling through the tracks. It was like a stage with each body lit differently. One of my primary interests is to show how the medium works, its play of first-hand experience and photographic experience.

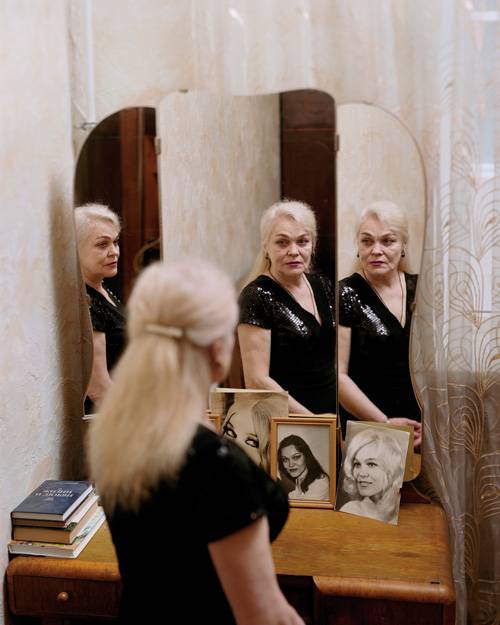

LR: Which leads me to a question about your well-known preoccupation with pictures within pictures. I am sure this is the source of your reputation as a “conceptual” photographer.

KJ: I always have been attracted to seeing three-dimensional settings in relation to a two-dimensional image. I remember, for example, there was an FSA photograph [American Way, Margaret Bourke-White] depicting a billboard of a happy American family, and in front of it was a breadline of black Americans. Sometimes I would use an empty mat or hold up a postcard to a scene. Siskind always talked about the photo as object, and what I was doing is really a form of collage.