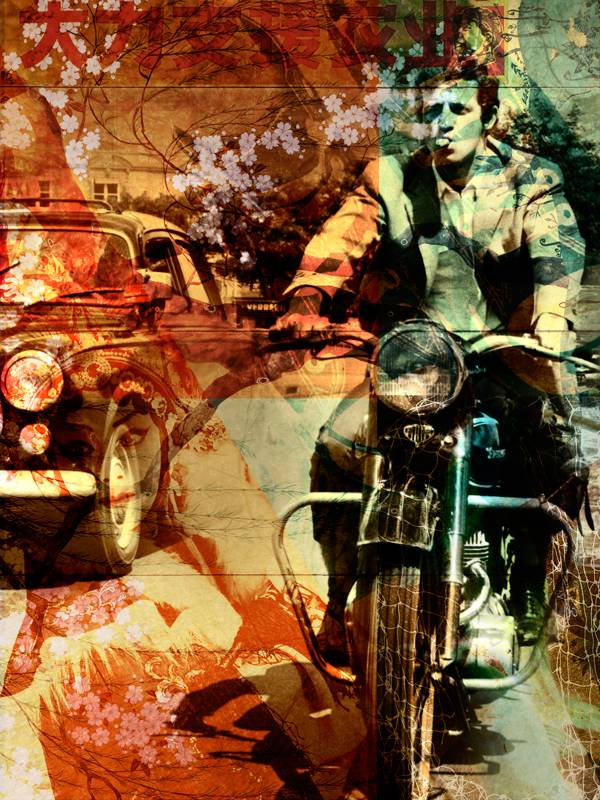

Like a fault line in the surface of appearances, photo collage opens up in periods of social stress and political obfuscation. In the 1880s, the playful cut and paste of Victorian albums betrayed a skepticism about photography’s ability to sustain memory and maintain the connection to a tradition that technology was rapidly effacing. In the 1920s and ‘30s, collage mobilized images against themselves, recombining them in political narratives that also revealed the penetration of a burgeoning mass media into every strata of society. Its reappearance today heralds new anxieties. Impelled by digital technology and unprecedented forms of mass social communication, photo collage emulates the texture of a hypermediated visual environment. Where earlier 20th-century collage artists like Hannah Höch deliberately let the seams between her images show in order to represent the rawness of colliding elements in a chaotic society, contemporary artists such as Max de Esteban, whose photograph Facelessness is on our cover, often layer images to mimic the experience of digital immersion – in combinations of imagery that is sourceless, familiar, and immediate. Esteban’s earlier work featured, among other things, X-ray-like images of outmoded communication technology, from the typewriter to the audio tape cassette. These were auguries of a more advanced technology that

renders the significance of images wholly malleable. Heads (in this case of a movie icon) are not the only things that roll through digital space; everything and anything that can be represented photographically might show up, imparting a dreamlike unreality not just to the Internet but to actual experience. In the exhibition Heads Will Roll at Klompching Gallery in DUMBO (September 12-October 30), the Barcelona-born de Esteban approaches the pessimism of one of his intellectual heroes, the Romanian philosopher Emil Cioran. Says Debra Klomp Ching, “His work is grounded in a rigorous conceptual framework, which is why even in contemplating the demise of humanity, he offers us something positive – a commitment to add to the sum of our knowledge.” Younger contemporary photo artists might see the potential for liberation in a decentralized media world, where users (or consumers, if you will) have the power to recontextualize and revise everything that comes across their phones or screens.

De Esteban is old enough to have experienced the propaganda and repression of Francisco Franco’s dictatorship in Spain, so his suspicion of the way images can be used likely runs deep. Does the tide of images erode an awareness of being in the world (as opposed to simply looking at it passively) and with it a sense of the lived reality of others? The apocalyptic tone of Heads Will Roll may stem from the conviction that any technology that overwhelms the immediacy of being with images undermines the possibility of true human solidarity. People become a faceless audience for fantasies, propaganda, distortion and marketing. Like Cioran in his aphoristic philosophizing, de Esteban, in his images, invites us at least to flirt with the temptation to exist, if only by showing us the many ways we have developed to evade that responsibility.