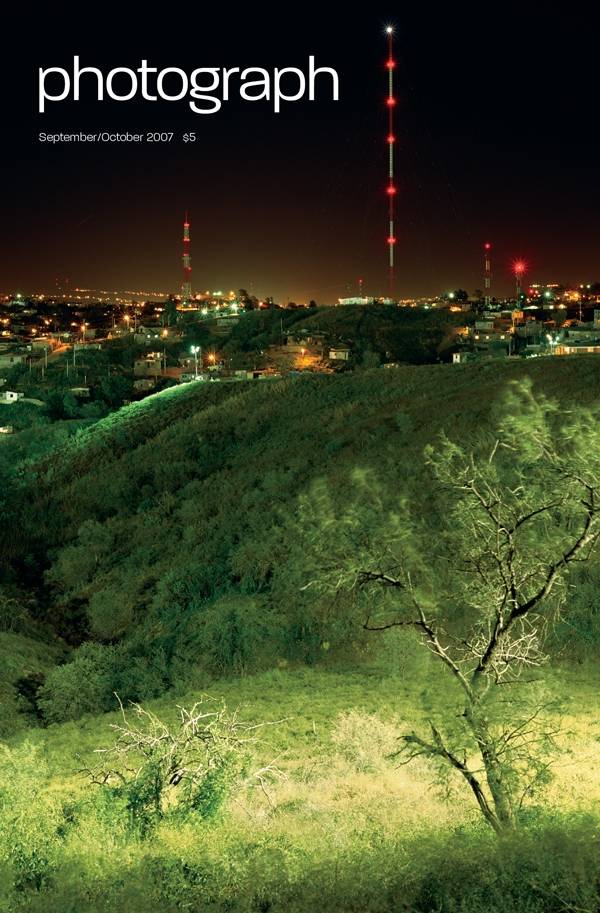

Perhaps the greatest platitude in the modern world is the desire for peace. It trips off the tongues of warlord presidents and repressive dictators, of conscienceless revolutionaries and campaigning religious leaders out to convert the world or cleanse it. Where is our Flaubert, with his Dictionary of Received Opinions, to reveal the deadly emptiness of this nostrum? Perhaps it is Simon Norfolk. For two decades, in ruined places from Rwanda to Afghanistan, Norfolk has amassed a stunning catalogue of death and destruction. It reveals that modern society is dedicated above all not to peace but to war—to planning it, fighting it, and developing its weapons. “Simon shows us the ruins of our tomorrow,” says Bonni Benrubi, whose New York gallery is presenting a selection of ten works by the artist (September 20–November 24). Also in the fall, the photographer’s work from Beirut is on view at Gallery Luisotti, in Santa Monica, California (September 15– November 3). Iraq has been without doubt the most photographed war in history—a war, moreover, that did not need to happen. Many of the images simply repeat clichés of the battlefield. In contrast, Norfolk’s photographs, shot with a 4 x 5-inch view camera, arrest viewers with their detailed implacability and Claude Lorrain-like painterly light. They force us to contemplate the sheer magnitude of the firepower unleashed: in the shattered modernity of Rashid Street in central Baghdad, or in a yard of stately palm trees littered with rocket shells. But Norfolk’s projects also look beyond the battlefield to the technology that makes these battles possible, and, beyond that, to the fantasies of threat and control that animate our war-making. Above the arc lights and burnt hills of Nogales, Arizona (our cover photograph), stand the radio surveillance towers of a growing system of border control. Norfolk has photographed surveillance and computer systems around the world, and as beautiful as such photographs are, “what you see is not all that you get,” says Benrubi. The towers of Nogales are a poetic synecdoche, standing for the larger role of technology in defensive thinking and global politics. “All of this work, I might even call it ‘Toward a Military Sublime,’” Norfolk said in a recent interview. “Because these objects are beyond: they’re inscrutable, uncontrollable, beyond democracy.” And of course, all built and operated in democracy’s name. This is the paradox of the world’s only remaining superpower, that it imprisons in the name of freedom and kills in the name of peace. No wonder then, that in the face of such hubris, Norfolk entertains fantasies of apocalypse. He titles the show at Benrubi “I Met A Traveller From An Antique Land…,” quoting Percy Bysshe Shelly’s famous poem “Ozymandias.” The poem contemplates the ruins of a once great and warlike civilization. It includes the memorable line that could be Norfolk’s motto: “Look on my works, ye Mighty, and despair.”

Categories