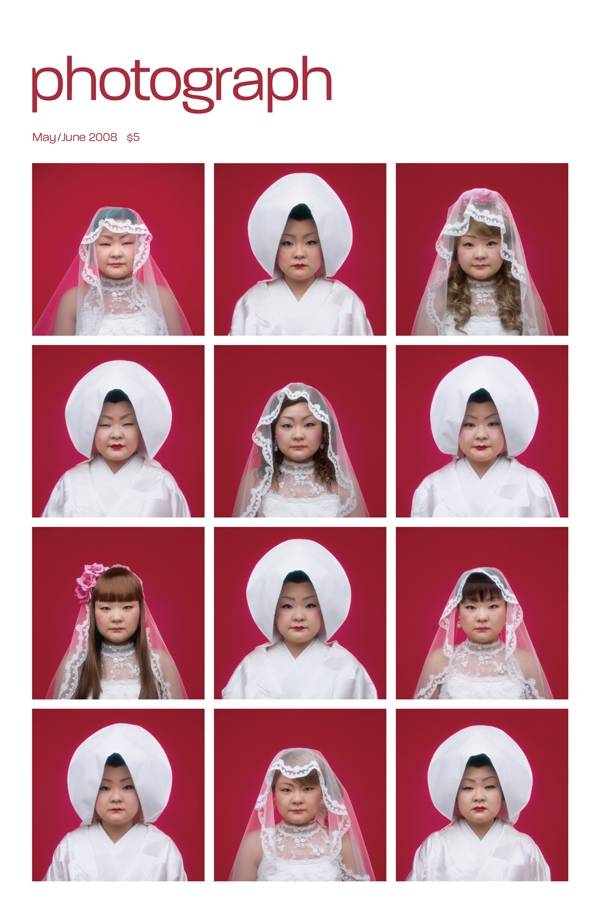

Photography is as leveling as a baseball bat in a room full of fine china. A globalized technology almost from birth, wherever it appeared it rearranged the cultural furniture, flattening native traditions of representation and following the same trajectory of development: from early experiments to pictorialist atmosphere to sharp-edged modernism and, as transmission expanded, to a transactional currency driven by social media. Yet local influences interrupt the diffusion, resist the tide of sameness with distinctive practices linked to indigenous traditions. Yoon Ji Seon’s work dovetails with contemporary preoccupations about women’s identity but frames the questions in archaic, even mythic terms, nourished by her Korean background. Her self-portraits, on view at Yossi Milo Gallery through December 5, incorporate photographs into rough hand-sewn effigies that resemble primitive masks. Milo was drawn to the work initially for its contribution to a tradition of self-portraiture represented by Nikki S. Lee and Tomoko Sawada, both of whom are preoccupied with the social construction of identity and how we read other people’s appearance – the modern problem of masking. “Her work appeals, as well, as a probing commentary on the expectations and alterations of beauty among youth in current Korean culture,” Milo says. Yet the currents tapped by the work, by what Milo calls its “confrontational, visceral imagery,” run deeper than changing social mores. The mask in the cover photo, animated by the “eyes” of a photographic print and made alarmingly present by the compulsive handwork of the stitching, transforms a represented expression into a glimpse at a primordial state of being. Rather than concealing, the mask discloses an elemental aspect of identity that we rarely encounter in contemporary social life (where we wear another kind of mask) – and never see represented in contemporary photography, perhaps because it resides beyond the medium’s capacity to render. Her work recalls outsider art, with its disregard for medium specificity and its psychological directness. Closer to home, it recalls Korea’s traditional theatrical masked dancing – talchum. Korea has many types of masks, instrumental in everything from comic performances to shamanic rituals. With such a background, it seems almost beside the point that Seon’s work extends the boundaries of photography. The artist doesn’t question the nature of photography but instead exploits its realism to bring a dimension of the uncanny to her representations – breathing life into cloth and thread already half animated by the obsessive energy of her sewing. Although they hang on a wall, these masks are Seon’s doubles, not mere images of her. They walk a line between reality and imagination, power and terror, image and performance. Above all, they seem to give the artist back her original face – or faces – her true and essential face that has been hidden behind the roles she must play as a woman in a modern, spiritless, image-obsessed world.