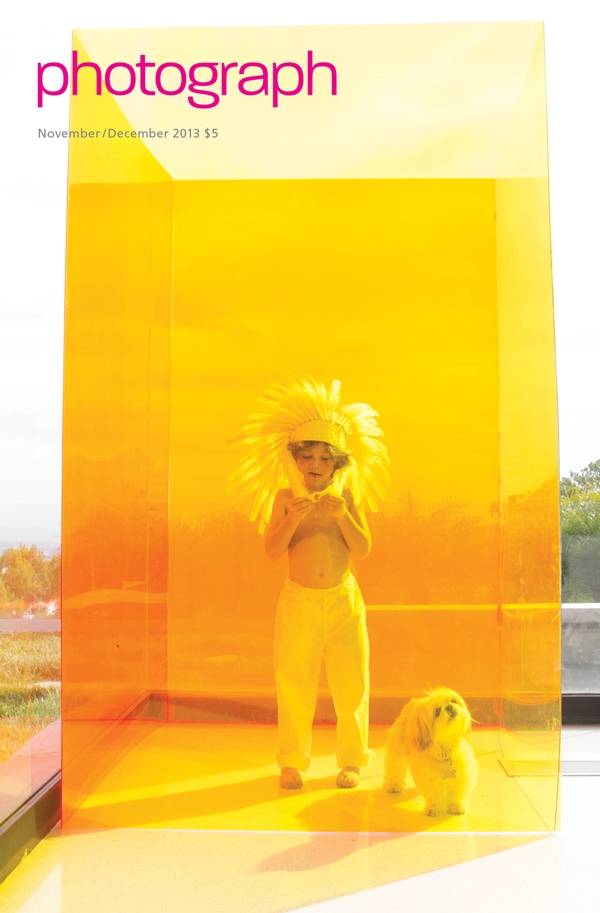

It must be the nature of camera work to provoke restlessness. With its narrow technical limits and its ontological straight jacket (camera here, world there), photography is that medium that is so easy to pick up and so frustrating to stick with. Isn’t there more? Something else to be shown, some other way to get at the nature of things? Follow most of the canonical image makers into their darkrooms and archives—or consider their entire careers and not just a phase—and you find the experimental, the idiosyncratic, the deeply personal or quixotic pathways that challenge the standard estimation and the signature style. So Walker Evans was as involved in the New York subway as he was in the American heartland, and Nobuyoshi Araki could shift from delicate autobiography to raunchy bondage catalogue without missing a beat. Not to mention Kertesz’s distortions, David Douglas Duncan’s Prismatics, and Evans’s own fascination with the Polaroid SX-70. Contemporary photographers seem to understand this instinctively. For many of them, photography is not about style and vision but about opportunities and appropriations, and their one-person exhibitions often resemble group shows. The photographer Tierney Gearon is not afraid to change gears. As her dealer Anna Walker Skillman remarks, “She does things her way, and she can’t be confined.” In the exhibition Colorshape at Jackson Fine Art in Atlanta (November 8-December 21),

Skillman shows us an unexpected Gearon, a more abstract and conceptual artist. Gearon is best known for The Mother Project, in which she documented both her mother, suffering from mental illness, and her own children. That project was provocative and controversial, and marked a dramatic departure from her career as a model and a commercial photographer. For Colorshape, Gearon has continued the subject of childhood but put a box around it—literally. For each of the photos, including the cover image Indian in a Box, she has set up her subjects inside a colored Plexiglas construction. The Plexi suffuses the light with a hue and temperature, and transforms the young subjects from documentary occasions to apparitions. No camera filter or post-production software could approach the same quality of light, and Gearon’s step into abstraction suddenly affiliates her with a long lineage of color experimentalists, from Moholy-Nagy to John Baldessari. The reflective aspect of the material also brings the scene behind the camera into the picture. Yet as Skillman points out, the effect is more intuitive and emotional than systematic and investigative. “There’s a playfulness about the images,” she adds, “and a protective sense as well. She’s creating a light-filled container around the children.” In these photographs, it’s as if childhood is its own shield that her children carry into the world. Gearon is closer in sensibility to Julia Margaret Cameron than to James Turrell. And to adults on the outside looking in, the photos may help recall the traces of our own light-filled worlds.

Categories