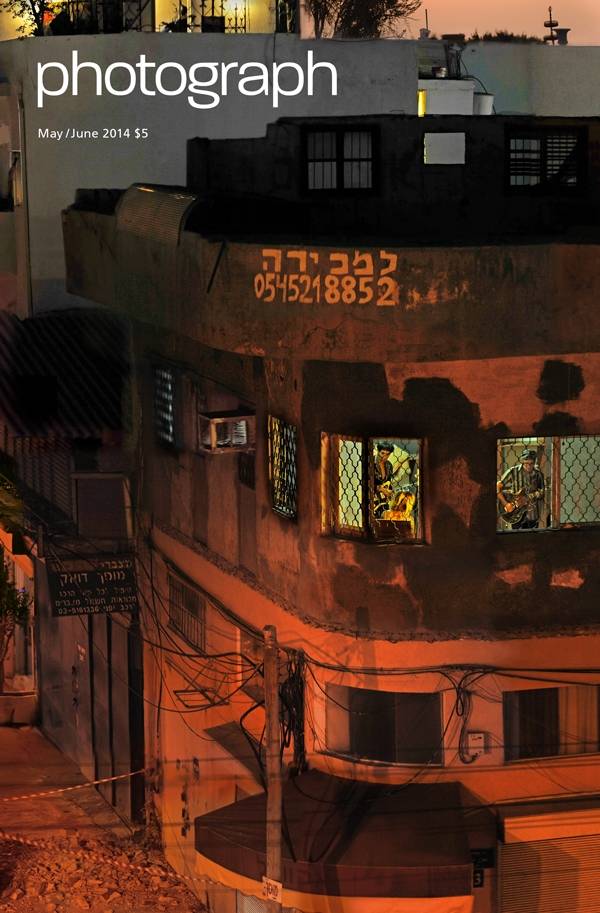

The metaphor of photography as a window on the world seems unavoidable, which is probably why so many photographers have made entire series of pictures looking through them. It creates a double frame, so to speak, and signals that what you see in the picture will be a combination of voyeurism and imagination, an invitation to scrutinize unobserved, like Jimmy Stewart’s character in Alfred Hitchcock’sRear Window, to meditate at length rather than to glance, register and move on. For those with a long attention span and a habit of investigation, the work of Israeli photographer Barry Frydlender offers the rewards of such stationary viewing. For over a decade, Frydlender has been using the street corner he can see from the window of his house in Tel Aviv as the stage set for photographs that articulate the complex changes taking place in Israel. But he does not simply document those changes, he convenes them. He constructs his photographs from hundreds, even thousands, of digital images he takes over a period of time, sometimes years. Reality is not staged but rearranged. In the cover image, Night Rock, for example, which he worked on between 2011 and 2014, we can’t help noticing the combination of decrepit infrastructure and hipster rock and rollers — seen through yet another set of windows. It’s a dead giveaway to anyone from Brooklyn that gentrification is in progress, and the more we look, the more we see subtle evidence of change, including the decorative trees in containers on the street — incongruous with the rubble and police tape we also see there. The photograph is on view with six others at the Andrea Meislin Gallery in Chelsea from May 8 to June 21. As Meislin points out, it helps to know that Frydlender lives in a section of Tel Aviv near Jaffa, a predominately Arab area, and the tower we see at the top of the hill is most likely a mosque. There is also a richness to the garden-like vegetation of the hillside in the background that suggests the exotic atmosphere of A Thousand and One Nights. “In these photographs,” adds Meislin, “the artist tells us an alternative story of Tel Aviv, within which there are many smaller stories.” We look for those smaller stories in all Frydlender’s photographs, including the unsettling Raid, in which a police action occupies the scene. There’s a sense of these raids being so common that we don’t even ask what their goal is, or whose space is being invaded. Instead, such events weave themselves into the fabric of daily life. On Frydlender’s street, actions are often ominous or inscrutable, but depending on how you read them, not without hope. At the end of the street in Night Rock, light shines through an open door. It leads to the darkness beyond, an entrance point to the secret garden of Jaffa perhaps, or an exit from a dead end street in Tel Aviv. In either reading, a path by which borders can be crossed.

Categories