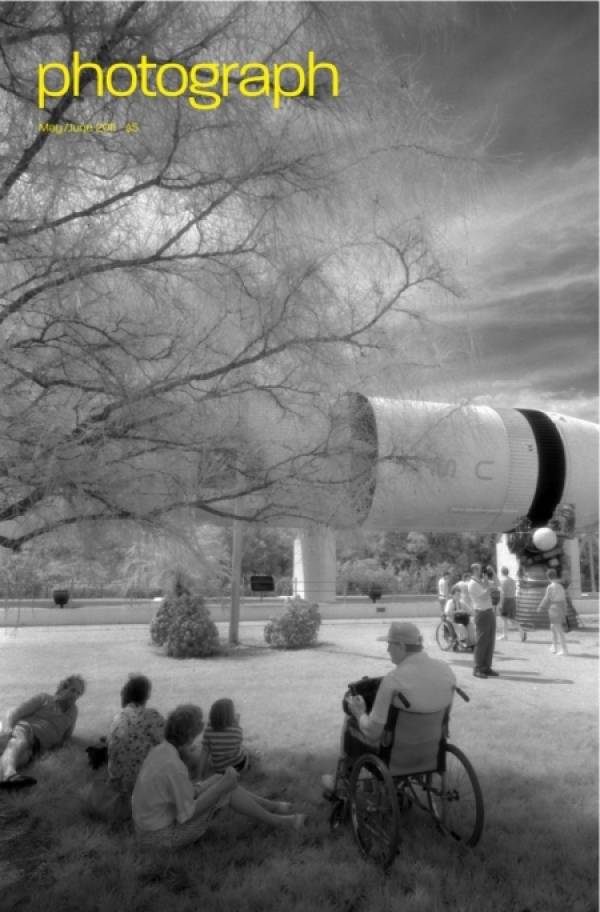

Frank Zappa once described Columbus, Ohio, as a town disguised as 1955, and for America, it may always be about that time. As a nation, we continue to see the world through a mid-century lens, despite every piece of alarming evidence to the contrary: the maledictions of foreign enemies, the labels on our products in unintelligible script that read Made in China, the depopulated urban centers, the catastrophic weather patterns. In consequence, America, believer in its own perpetual innocence, has created a unique form of nostalgia—a nostalgia for the future. Ana Barrado is its chronicler. Faux naïve and precisely calculated to insinuate themselves between memorabilia and dream, her photographs are memorials to a tomorrow that never quite happened as anticipated but whose vision we can’t let go of. The gigantic rocket, looming over the picnickers and oblivious tourists, captured in a memory-soaked haze of gelatin silver (toned with selenium)—when did it happen? Weren’t we going to put a man on the moon? Someday won’t we have colonies there? Maybe if we survive the possibility that one of those rockets could be aimed at us and carrying a multimegaton payload. But didn’t treaties take care of that, or won’t they soon? For viewers of a certain age, the sense of dislocation induced by the 25 prints on view at Deborah Bell Photographs in New York (May 6–June 25), mounted in collaboration with the San Francisco dealers Paul Hertzmann and Susan Herzig, is, in Bell’s words, “whimsical and eerie.” Or perhaps vertiginous and frightening, like an episode of The Twilight Zone. Barrado’s Family Outing, Spaceport USA, 1991, and her other images, all shot in space-themed parks in Florida and New Mexico, depict not some archaic past but the recent world of the 1980s and ’90s, whose tourists marvel at (or ignore) the relics of our once-great leap forward into space. It’s as if little had changed in the intervening decades, and it is all still here, the bubble-headed space suits, the astronaut chambers, the sleek (and slightly undersized) rockets and the (inflatable) space capsules. All of them are bathed in a bright, even interstellar, sunlight, exaggerated by Barrado’s use of infrared film, another technological miracle now superseded, ideal for delivering cosmic epiphanies that transform precisely nothing. Like characters in a story by Jorge Luis Borges, we can’t help asking if it is yesterday or tomorrow. Beyond Barrado’s preoccupation with simulacral America, the ambiguities of time are her true métier: the Argentina-born artist knew that country’s two great metaphysical fictioneers, Borges himself and Julio Cortazar. But time is not simply a game played with images: there are hints in the photographs of detritus and decay, breakdown and potential apocalypse. Barrado seems to say that beyond our fantasies, or perhaps because of them, the future is destined always to be a disappointment. And the tomorrow we’ve lost will always beckon more brightly than the tomorrow we face.

Categories