“I loved the quiet places in Kyoto, the places that held the world within a windless moment. Inside the temples, Nature held her breath. All longing was put to sleep in the stillness, and all was distilled into a clean simplicity.” — Pico Iyer

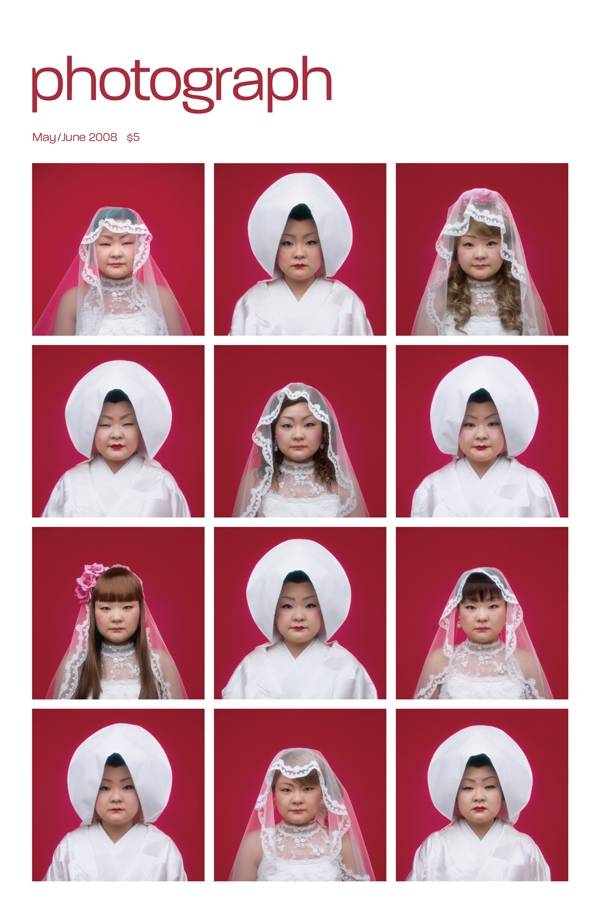

In 2004, Dutch photographer Jacqueline Hassink set out to find and photograph those places where nature held her breath. Hassink visited Kyoto eight times in ten years, creating a series of photographs in 34 of the city’s 1,600 Buddhist temples. At first glance, the project, published as View, Kyotoand on display in the new Chelsea location of Benrubi Gallery from March 26 to May 9, seems like a giant postcard of the ancient city (which today scarcely exists). Typified by the cover image of the temple, Hösen-in, here are the manicured gardens, the immaculate spaces, the empty stillness of an architecture that values simplicity and seems to defy time. But as gallery director Rachel Smith points out, Hassink pursues some very particular goals in the photographs, goals that link this personal investigation to her more overtly political projects such as The Table of Power. “In both cases there is a connection between ritual and architectural structure,” says Smith. “Hassink explores how a space is shaped or stamped when no one is there to occupy it.” With Kyoto, Japan’s ancient capital, the exploration is philosophical and aesthetic. The temples hold her attention not simply because of the precision of their interior geometry but because they express a distinct relationship with nature. As Smith says, “What’s outside is inside.” Their open porches and partitions create a flexible and constantly shifting border between garden and temple, interior and exterior, nature and mind. Once we see the temples as a means to break down the divisions of experience, the photographs reveal to us many glimpses of the paths to one-ness. In Hösen-in, for example, there are views but no actual windows, for the walls are sliding panels. The temple floor segues into the garden beyond with barely a step down. Interior walls are scarcely more than rice-paper panels that transmit light, and in the subtemple of Myoshin-ji, nature’s presence is felt in the in-most rooms through the adornment of painted wall panels depicting exquisite natural scenes. Although the scale of these temples can be grand, human activity is conducted close to the ground – on tatami mats, low tables, and kneeling cushions. Likewise, the human hand extends into the natural world, in gardens that consciously flirt with the designed and the disordered. The intricate consistency of traditional Japanese aesthetics has fascinated Westerners for centuries, and Hassink is the latest in a long line of photographers to feel its pull. The final image in the series View, Kyoto, however, reveals that Hassink has sought not merely to image the “Kimono mind,” as Bernard Rudofsky called this traditional sensibility, but to inhabit it: the photograph shows the artist dressed in the costume of a geisha.