Referring to the strange vicissitudes of a particular American dream, circa 1970, Robert Adams wrote, “The puzzle became how to live inside.” That dream was one of nature, open space, and expansive light that lured an expanding population west—and lures them still. What they found instead, as the exhibition Landscapes of Harmony and Dissonance, on view at the Getty Center in Los Angeles through May 28, makes clear, was a life inside: with nature pushed into the background and the “landscape” becoming one of suburban confinement. This comprehensive sampling of Adams’s work is the first to show us both sides of this increasingly relevant artist: the nature photographer who has pursued a shifting vision of the sublime, and the chronicler of nature’s displacement by the built environment. It includes some of his earliest work, the deceptively simple—and deceptively picturesque—painted wood architecture of the west.

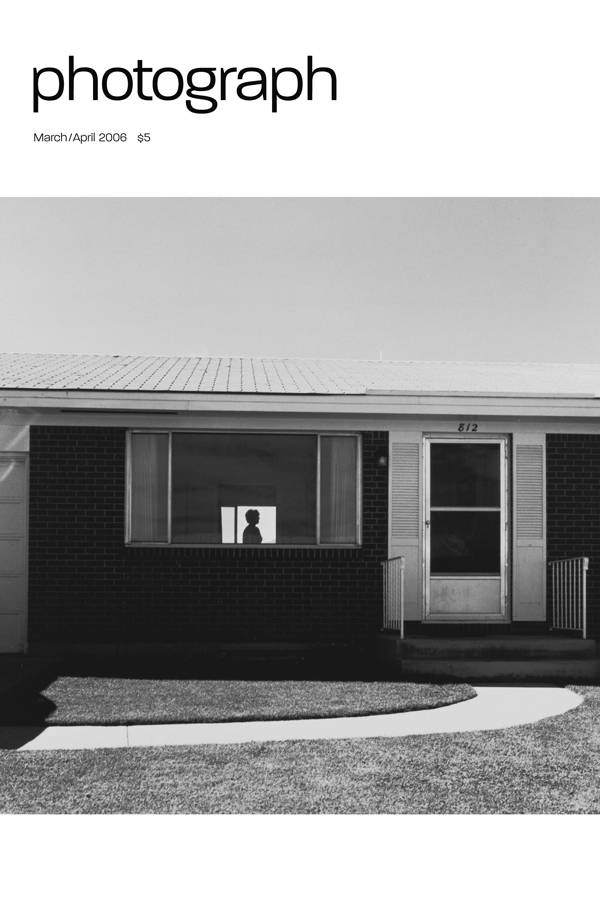

“What makes Adams so important now,” says Getty curator of photography Weston Naef, “is the quest for harmony that runs through his work, even when it appears to be about contradiction and dissonance.” It’s a quest that has produced images that don’t allow us to condemn or criticize what has happened to the landscape without at least understanding the dreams and desires that drove the changes. After all, what looked 30 years ago like an aberration or an alarmist prophecy about sprawl is now all too familiar, and Adams long ago understood the ambiguity of this transformation. Is the woman in the window of the perfectly composed and centered cover image a victim of suburbia’s inner isolation, alone in a cultural wasteland that adumbrates nature’s desolation? Or is she, like so many of the characters in the paintings of Edward Hopper, which this photo resembles, caught in a moment of private reverie, perhaps contemplating the light that suffuses and almost manages to transfigure the banality of her surroundings? “In some profound sense, these people found what they were looking for,” says Naef.

Adams was one of a group of 1970s photographers labeled by former MoMA curator John Szarkowski “the new topographers,” documentarians of an American collision between nature and culture, and he has the objective gaze of the surveyor. But he is also an eloquent writer and has the sympathy of a poet (his sister is one). He is willing to confront the terror concealed in comforting regularity and the inadmissible beauty in devastation. “As with any poem,” says Naef, “you have to scratch below the surface to grasp the meaning of these photographs. Adams’s work reminds us in each picture how complex experience really is.”