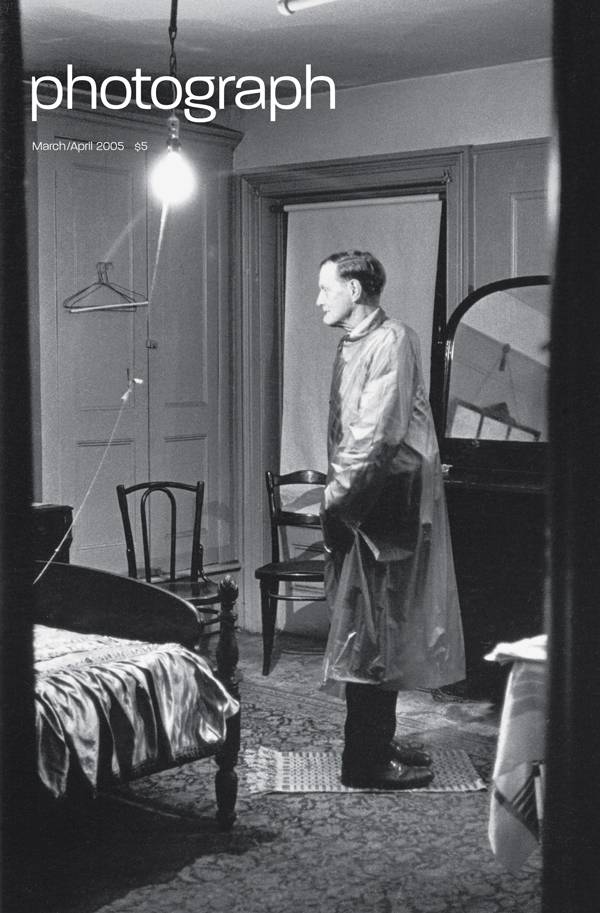

A poet once wrote that art is craft and need, and no photographic artist invested her craft more intensely with need than Diane Arbus. Decades after her suicide in 1971 and more than half a century after her first pictures, it’s still possible to feel the pressure she put on every image, not simply to tell a hitherto untold truth but to bridge a divide. Photography is the strangest art, promising a privileged intimacy and enforcing a distance: you can look but never touch. Unlike Winogrand or Frank or other “new documentarians” of her time, Arbus could never just point and shoot. She had to get inside the spaces and the worlds of the Backwards Man(our cover image, from 1961), the hotel rooms, circus tents, female impersonators’ dressing rooms, and suburban living rooms, which she recognized as one of the strangest places of all. Even on the streets, she became a space invader, like Weegee, but with a different hope and a different sense of risk, that seeing might become being. She called photography “the condition of being on the brink of conversion to anything.”

In the first retrospective in more than 30 years, organized by the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art and on view at the Metropolitan Museum of Art (March 8–May 30), we can follow her over and over to the brink of conversion. In addition to the more than 300 prints displayed in the temporary exhibition galleries, the show recreates her library and her working milieu, with notebooks and pictures of her bulletin boards. “I am hoping this show will be as shocking as the posthumous 1972 exhibition at MoMA,” says Met curator Jeff Rosenheim. “It will bring us back to the raw emotions provoked by the contact between viewer and subject.” That’s a high hope, for Arbus gave voyeuristic permission to so many photographers that the territory she opened up is now crowded with cliches, from snake handlers to sex workers. The marginal is now the mainstream.

The difference, as Rosenheim contends, is the quality of attention Arbus paid her subjects. If the Backwards Man suggests a metaphor for prophecy, it is because Arbus saw him that way, not as mere oddity, social type, or occasion for career advancement, but as a sign and a wonder, bearing a message. “You can turn away,” she once wrote about photographs, “but when you come back, they’ll still be there looking at you.” The message might be as complex as the Backwards Man’s unfathomable life or as simple as the assertion that he, amazingly, exists. It might be experienced as doubt or affirmation, or both together. Such a paradox is central to photography, and no other artist confronted it more eloquently than Diane Arbus.