Wilderness, said Stewart Udall, former secretary of the interior, is an American idea. The lure of wild, untrammeled nature was an offshoot of the founding Puritan errand into the new world, and it became a key element in the myth of the nation – bigger, grander, purer than all the rest. The creation of the National Park Service in 1916 enshrined that ideal and keeps it alive today. Yet most Americans know these wide open spaces only through photographs, and photographs were instrumental in creating the park system. The interaction between preservation, promotion, and photography is the subject of a major exhibition celebrating the hundredth anniversary of the national parks at George Eastman Museum (through October 2) and an accompanying book from Aperture, Picturing America’s National Parks. As curator Jamie Allen points out, the very places that became the most famous parks – Yosemite, for instance – were already implanted in the popular imagination through photographs by Carleton Watkins, Eadweard Muybridge, and others before the movement to set aside land began in the 1870s. Ansel Adams experienced Yosemite as “that great earth gesture,” a spiritual experience, but his photographs would help transform the vision of it into a cliché, hardened by the physical parks themselves. It is just one of the paradoxes of the parks that their facilities are located to confirm the “views” of photographers, which then encourage more iterations of the same image. And, adds Allen, “their work of celebration and promotion has led to modifications of the very places they hoped and helped to preserve.”

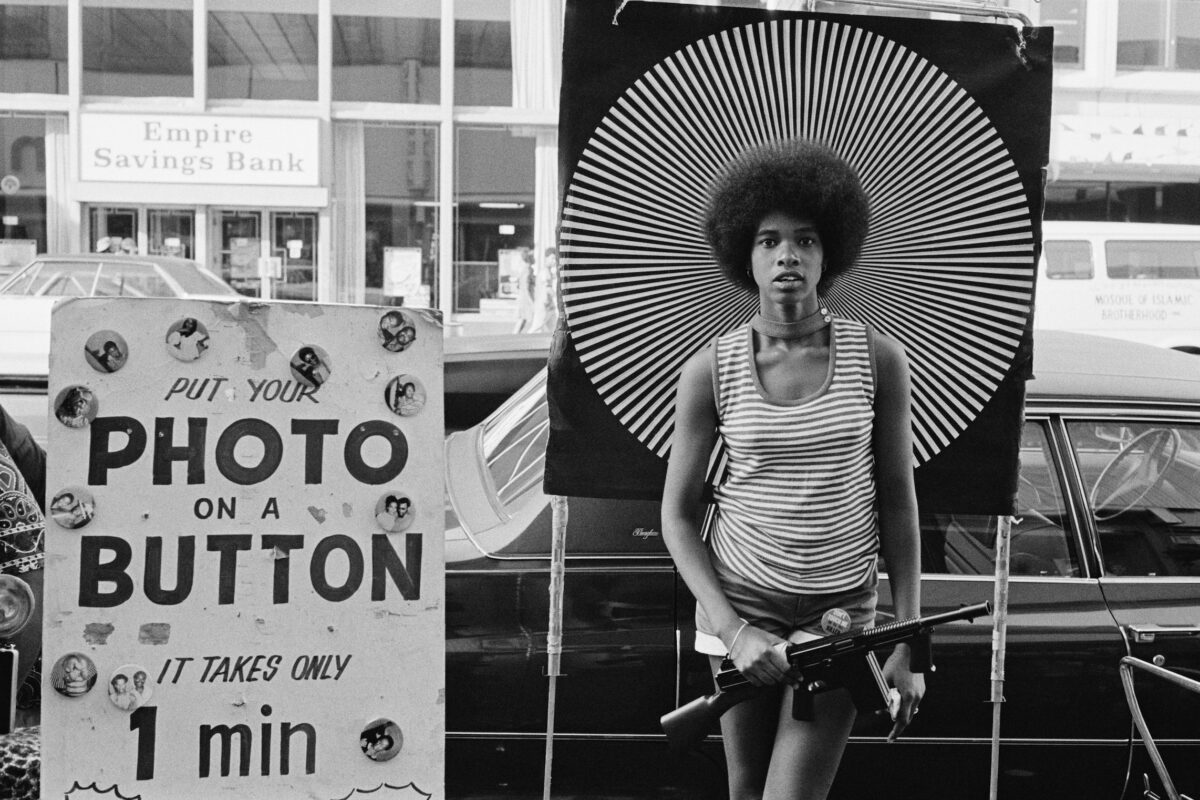

To give a sense of the full complexity of this relationship of nature, nation, and image, the exhibition includes historic photographs, contemporary works, and vernacular images. The snapshot is as important to understanding the dissemination of a wilderness iconography as any Sierra Club photograph by Eliot Porter. It also sheds light on the cover image by David

Benjamin Sherry. Sherry’s red-hued image of sunrise in Death Valley recalls the formal undulations of Edward Weston’s famous

photograph, but it is also a deliberate attempt to find a new vantage point on a familiar location. As Allen says, “Sherry’s goal is to find a way past the clichés in order to arrive at a more personal experience of place.” Sherry achieves that by transforming the scene through the use of film and analogue printing that pushes his view to a chromatic extreme, injecting emotion and expression into what would otherwise appear a formal exercise. In a similar vein, Binh Danh’s daguerreotype of Yosemite explores his experience as an immigrant coming to terms with a national icon whose mythology is not his by inheritance. Personal as his story is, perhaps this is at the core of everyone’s experience of wilderness today – understanding why they visit and value such places. For when viewers look at the shiny surface of his daguerreotype, the first thing they see is not El Capitan but themselves reflected in the mirror of nature.