Kamoinge is a Gikuyu word that, roughly translated, means “a group of people acting together.” But for the black photographers who formed the collective in New York City in 1963, ”it represented an ideal,” says photographer Anthony Barboza, president of the group since 2004. That ideal was to address the fact that there was little awareness of or encouragement for black photographers. So the group came together to nourish each other. Led first by Roy DeCarava, in whose loft they often met, Kamoinge came to include such photographers as Gordon Parks, Louis Draper, and Parks’s daughter Toni. As Barboza points out, it is the oldest continuously operating nonprofit photography group in the country. Yet as important as members of the group have been in many different areas of photography, it is little known and infrequently exhibited as a group. Two galleries and a new book should give these photographers the attention their cultural effort has earned.

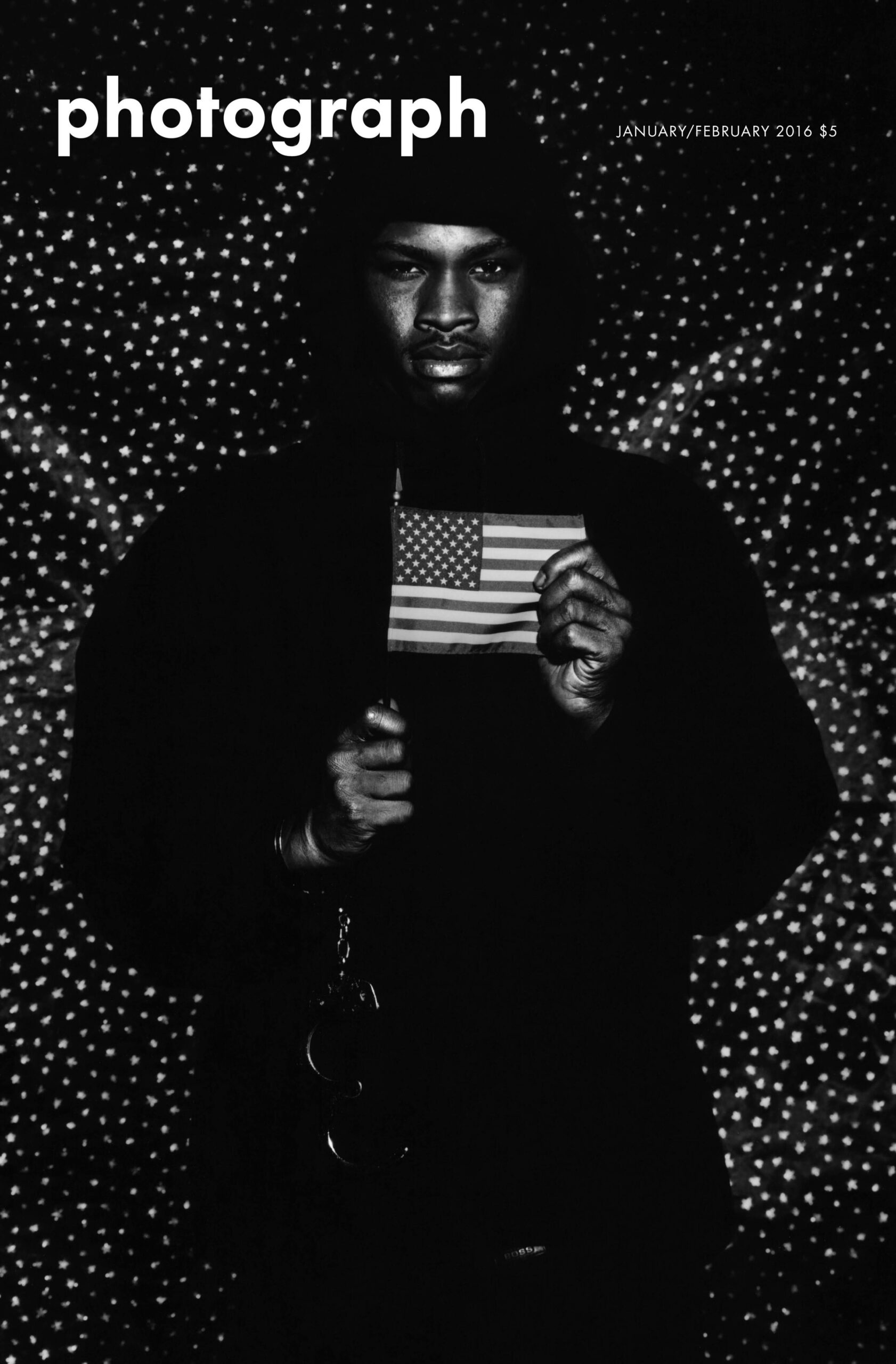

Timeless: Photographs by Kamoinge is on view at Wilmer Jennings Gallery in Manhattan (through February 20). It is accompanied by a book of the same name (see Vince Aletti’s review in this issue). Barboza’s early work is being exhibited at Keith de Lellis Gallery (January 28-March 12). The cover image shows Barboza as above all a maker of symbols.

Patriot was shot originally in the 1990s for an N.A.A.C.P. calendar, and its combination of flag, handcuffs, and title create the paradox that, in Barboza’s words, “forces you to think more than once about the image.” In the current political situation of fear and stereotyping of other minority groups, the image takes on renewed relevance. Barboza has had a varied career in photography. He has shot everything from fashion photographs for Essence magazine to an album cover for Miles Davis (You’re Under Arrest). “When I once met Minor White,” he says, “I told him I was confused because I was doing everything in photography and others were more specialized. ‘I like it all,’ I said. ‘Then do it all,’ he replied.” Yet what remains paramount for Barboza is what drew him to Kamoinge. “It is to make images that go beyond what you immediately see and know.” In the early days, critiques among group members pulled no punches, and everything was on the table, not just technique but politics, morality, and most importantly the spirit behind the work. “We had the goal of uplifting the soul toward what is universal,” he adds. To achieve that, Barboza learned from others like DeCarava. “But you can’t copy anyone,” he says. “Over time you come into your own, you become yourself as an artist.” His concept of evolving toward identity explains the title of the new book. “‘Timeless’ refers to the values we pursue and what we learn from those who have come before.“ For the collective’s most recent photograph, all members, past and present, are together – the living in person and the deceased evoked in photographs that the group members hold up.