When Robert Rauschenberg appropriated photographs for his combine paintings in the 1950s, it sent a message that photography was fair game for artists, and that they couldn’t care less for the pretensions of its traditional practitioners to a kind of aesthetic autonomy. However else it might be used, photography was an industrial process first and foremost, a central means of image production and distribution in Western society, and most of those images had nothing to do with art. The point of pointing the camera became pointing out the motives inherent in pointing a camera – and in looking at the results. You thrilled at Ansel Adams’s views of Yosemite or Edward Weston’s nudes? Better look the other way. Here comes the Pictures Generation.

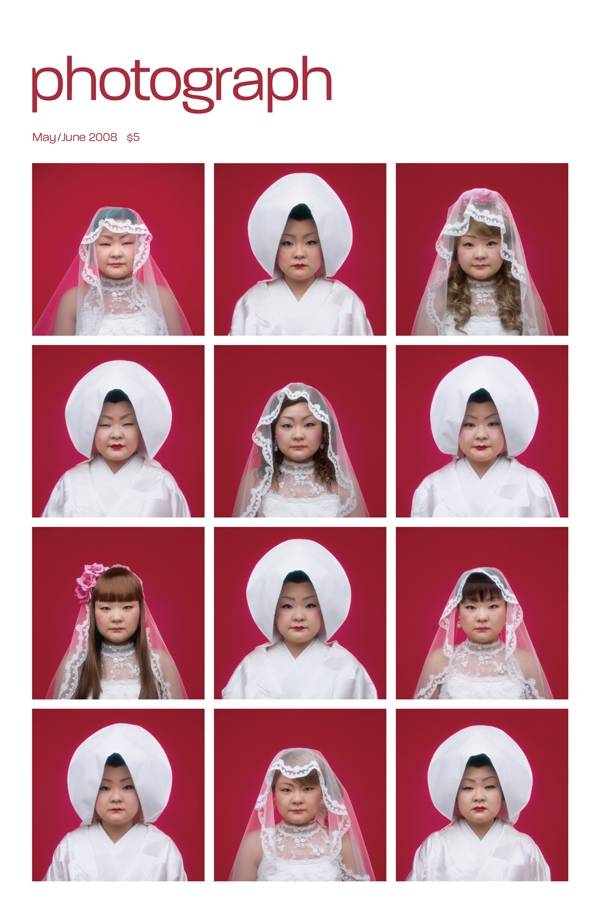

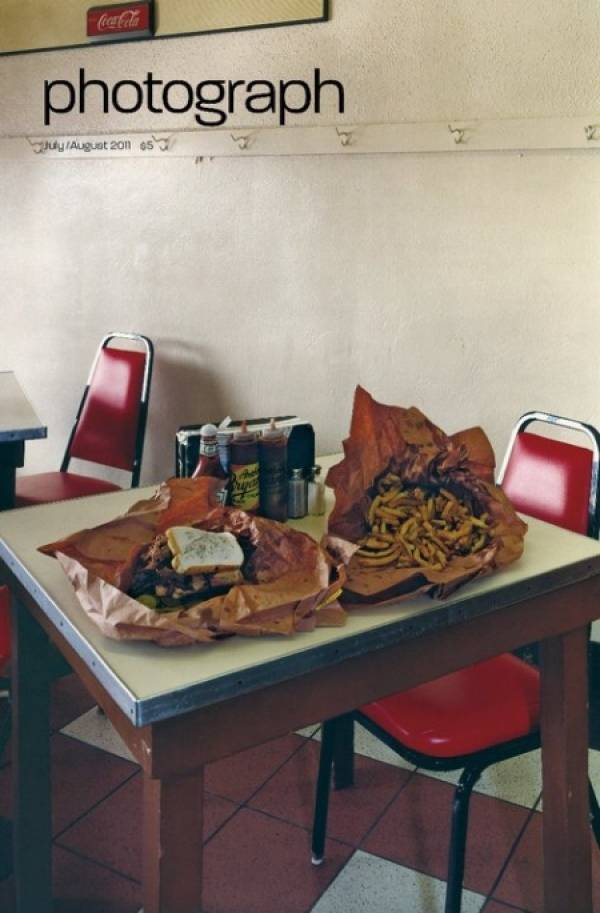

Christopher Williams wasn’t showcased among that generation of artists using photography, the likes of Cindy Sherman, Richard Prince, and Louise Lawler, but he belongs among them. A graduate of Cal Arts and a student of conceptualist John Baldessari, Williams has made the analysis of photography’s cultural position his form of camera art. His first major U.S. retrospective, The Production Line of Happiness, mounted by the Art Institute of Chicago (January 24–May 18) and the Museum of Modern Art (August 2–November 2) provides a detailed course in the technology, audiences, useages, industrial and commercial infrastructure and visual tropes of the medium. The show includes 64 photographs, as well as other elements including films Williams made at Cal Arts. The images are simple, pristine, and always on message. MoMA curator Roxana Marcoci calls them “visual essays.” On our cover, the tools of an antiquarian world (dark room photography) are displayed without nostalgia, like the presentation of specimens or a shop window display. But there is more here than meets the eye. According to the lengthy caption, the darkroom, which is still in use, is that of the Fachhochschule in Aachen, Germany. The title opens a door on a preoccupation of Williams’s – Germany’s role in the manufacture of photographic technology and the spread of photo techniques. The objects before his camera have histories, and so photos need their titles. Indeed, there is always more going on beneath the surface of these works, which most often reference some form of advertising. A picture of a light meter with a blurry image of a woman in green with green shoes behind it – also with a detailed technical title in German, revealing that the meter was made in the former East Germany – appears to be a complicated parable about the status and spread of fashion photography from a certain period. Says Matthew Witkovsky, curator at the Art Institute of Chicago, “Williams is always historically specific. He doesn’t ask what photography is but what it is used for at a particular time.” He’s also quirky, willing to cut a camera or a candy bar in half just to see what it looks like. Adds Witkovsky, “All great art has an element of the unplanned.”