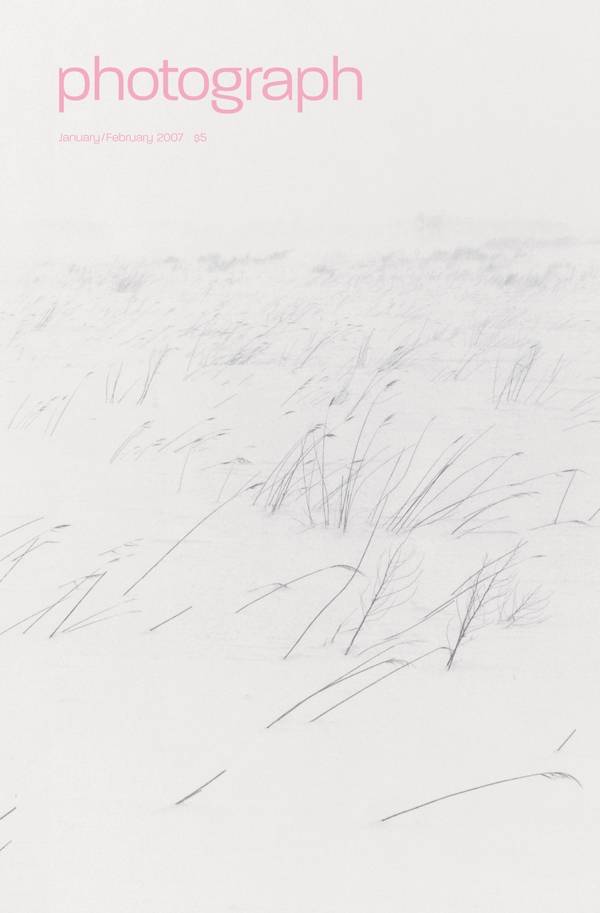

From the beginning, photography’s practitioners have asked themselves what the medium was: a technique of drawing or a mechanical means of reproducing the seen world? A device of science or a vehicle of art? And even as this method of imaging took dominion everywhere, photographers wondered if the camera might offer access to that which was hidden from plain sight, to evidence of things unseen: emotion, the spirit, time itself. The expressive nature of photography has its own history, from Fox Talbot’s experiments through Stieglitz’s Equivalents to the supernaturalism of Paul Caponigro and many other photographers working today, including Adam Fuss and Susan Derges. For them, the world of visible forms is a jumping-off point for other, deeper realities. Photography functions as a sort of spiritual Rorschach test, opening up the psyche by means of suggestive analogies. The image becomes a meditational instrument. And the images that work most powerfully are those that tell the least. Like Byung-Hun Min’s photograph from the series Snow Land, on view at the Peter Fetterman Gallery in Los Angeles from February 3 to March 24. It’s a field of grass in winter, nearly obscured by the whiteness of the snow. Hovering somewhere between drawing and painting, it registers as little more than a few lines on paper, strokes of a pencil. It suggests, too, marks of communication in an undecipherable language. For Fetterman, the appeal is mystical. “Our Western world is so cluttered with iPods and Blackberries,” he says, “that to see something so empty and elemental opens up the heart.” The Korean-born artist shares with his countryman Bon Chang Koo a thoroughly photographic commitment but one conditioned by Choson Dynasty painting—its precision, delicacy, and emotive restraint. The images in theSnow Lands series are all on the verge of disappearance, and like so many landscapes of traditional Asian painting, they seem to recede even as they rise up before us. Likewise, Min’s muted use of color echoes the traditional use of inks in painting. Min also devotes a painter’s attention to darkroom production and to the choice of paper, for these aspects of photography have a material reality that anchors our experience of the timeless in the rich particularity of the present. Perhaps all art does exactly this, and Fetterman notes that “the suite of images suggests a similar impact to Mark Rothko’s chapel in Houston. Both have a transcendental appeal that we could also call Romantic. They move us.” But analogies to Minimalism and to painting itself are misleading. Photography’s continuing fascination lies precisely in its stubborn refusal to let go the real world, the world of light and shadow, and to insist that what we see and what we feel are somehow congruent, the invisible and the visible two sides of the same coin. We are lost in the snow, and yet we know where we are.

Categories