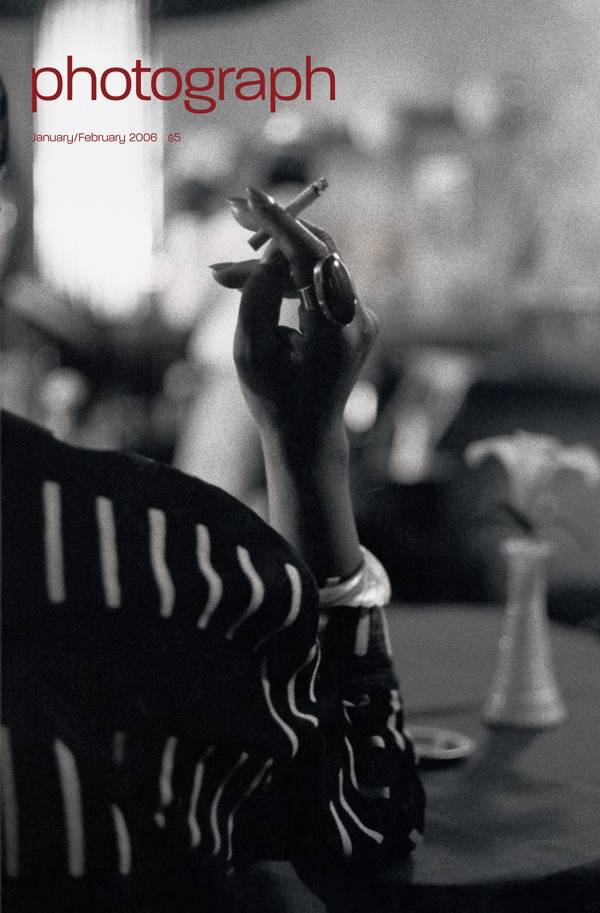

It’s a smoky lounge somewhere in Harlem, an after-hours club where the women are elegant and the music is, say, Johnny Hartman singing “Lush Life.” If you thought the photographer was Roy DeCarava from the 1950s or even Carl Van Vechten from the 1920s, rather than Gerald Cyrus from 1996, you can be forgiven. Because the exhibition Double Exposure: African Americans Before and Behind the Camera, on view January 14–June 18 at the Amistad Center for Art & Culture at Hartford’s Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art, is all about the interplay of past and present. Curators Lisa Henry and Frank Mitchell have brought together some 100 works from the Amistad Center’s rich historical collection and from contemporary artists such as Cyrus, Carrie Mae Weems, and Lorna Simpson. The exhibition suggests not only the range of African-American photographic achievements but also deeper affinities among artists across time. Says Henry, who assembled the contemporary works, “By now most everyone knows there are African-American masters of photography—James VanDerZee, Gordon Parks, DeCarava, and many others. We wanted to go beyond a mere list to explore continuities and discontinuities, and to make the past relevant.” Thus the exhibition is organized not by date but by broad thematic groupings, spurring dialogues, as Henry describes it, between works of different periods. Under the heading “Opening Up the Family Album,” for instance, Renee Cox’s pairing of family photos with her own self-portraits questions the domestic narratives constructed with such care by earlier families. And under the rubric of “Photographer as Muse,” which deals with, among other things, the ubiquitous genre of studio portraits, a rare daguerreotype by Augustus Washington, ca. 1851, and an elegant portrait by James VanDerZee, chronicler of the Harlem Renaissance, are displayed near a portrait by contemporary photographer Dawoud Bey. The juxtaposition reveals the deep debt Bey owes his precursors. On the other hand, according to Mitchell, who spent several years studying the Amistad collection, these dialogues lend the tintypes, cartes-de-visites, and ambrotypes a new currency and an unexpected gravitas, even though they might not always be regarded reverentially by current artists. “African Americans have been involved with photography from its beginnings, and for this exhibition, we are compelled to take the historic pieces seriously as art objects,” he says. “With family photographs, for instance, we are now asking who the subjects were, how the studios functioned, who were the artists, and what was the context of the images.” What emerges in this ambitious exhibition is a complicated vision of race and the camera, more like a series of refracting mirrors than a direct presentation. “We are not proposing a one-sided view of what it means to be African American,” adds Henry, “and we don’t mean this to be the last word. It’s our hope that the exhibition is the beginning of a different kind of discussion.”

Categories