For 29 years as curator of photography at The Museum of Modern Art, John Szarkowski showed us other people’s pictures—and helped us understand and appreciate them. Now we have a chance to look at his. An exhibition mounted by the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (February 5–May 15) and eventually making its way to his former employer in New York is the first retrospective of a career little known and, alas, underpursued. Surely no one would have wished Szarkowski away from the Modern, where from 1962 to 1991 he presided over photography’s full investiture as an independent art. Though he loved where photography had been, especially Ansel Adams, Edward Weston, and Eugene Atget, he critically embraced where it was going, through exhibitions that highlighted photographers as diverse as Diane Arbus, Garry Winogrand, and William Eggleston. But the reason he came to the attention of the Modern in the first place was his photography. His two Guggenheim Fellowship projects, one on the architecture of Louis Sullivan, the other on the Quetico region of northern Minnesota, not far from the Walker Art Center, where he had worked, revised standard practice and looked forward. For him, Sullivan’s buildings weren’t monuments but street presences made up of subtle and complicated details. In the woods, Szarkowski trapped viewers in the mazey tangle of nature’s growth without relying on a large format to bring them into the picture. Seeing the quality of what has been prompts the unavoidable question of what might have been. “I never intended to stay at the museum for so long,” Szarkowski remarks, “but because of museum schedules, you have to quit two years before you actually leave, and I never managed to.”

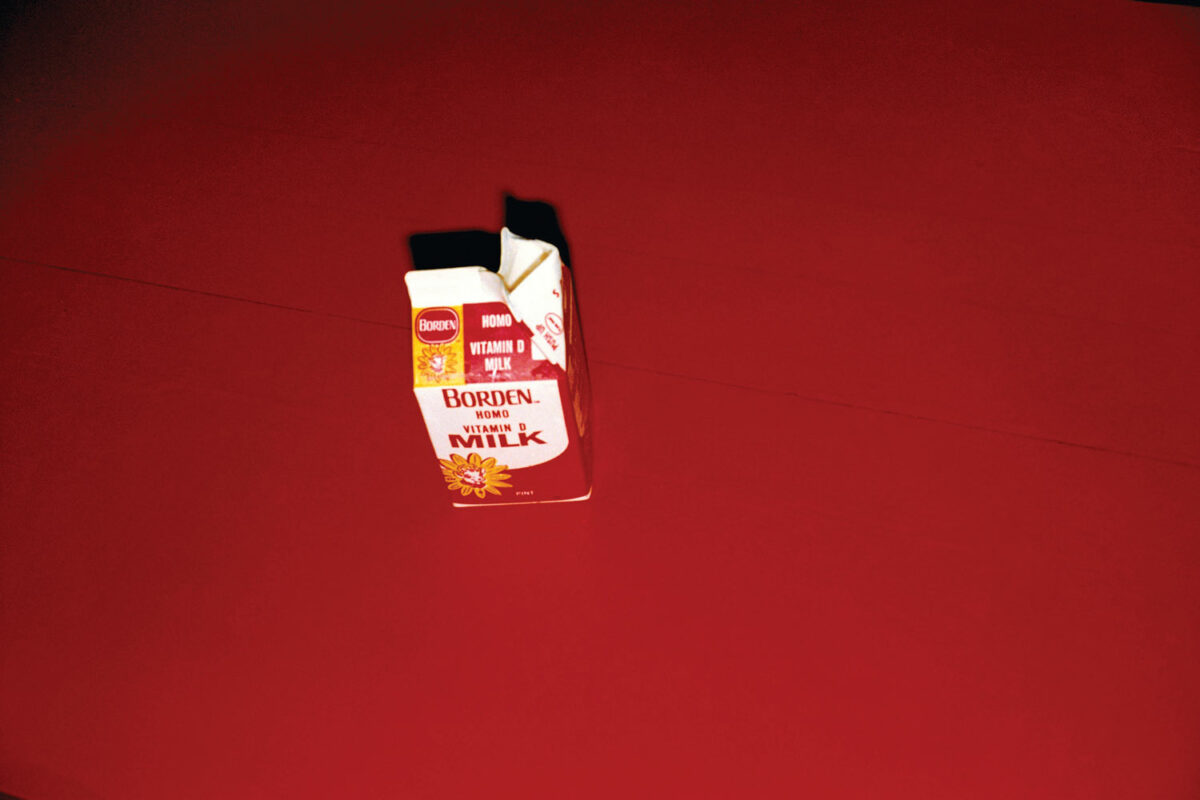

Szarkowski has been praised for his sly formalism, and it’s hard to disagree. The Walker Evans-ish screen door (1950) of our cover image is, as he admits, “not innocent of Mondrian. I tried it first as a horizontal,” he admits, “but then I reversed it and I could tell it was good.” Yet for SFMOMA’s Sandra Phillips, who organized the retrospective, formalism misses the point. “John’s pictures are deeply concerned with specific places in time, and that’s probably true for all the work he has championed,” she says. For Szarkowski, photography has always been an amalgam of what’s formed and found. The world is not enough, but it remains photography’s primary occasion. In his recent work, Szarkowski has concentrated on a small corner of that world outside his home in upstate New York. His pictures, most of apple orchards, are at once utterly simple and intricate, meditations on nature’s perpetual bounty and human beings’ temporary residence—gnarled bough and straight pruning pole. The symbols are hidden in plain sight, the images as resistant to critical comment as Keats’ ode To Autumn. “You go out day after day, you think you’ve got it,” he says, “but it only works sometimes, and you never really know why.