There’s no mistaking the work of Ming Smith. At Steven Kasher Gallery, which is presenting more than 75 vintage black-and-white photographs in her first major retrospective through February 18, visitors are immersed in an entirely singular aesthetic environment. Unusual angles, bright lights and dark shadows, blurry landscapes, and obscured faces are trademarks of Smith’s career, whose full breadth is covered here, from the 1970s until the present day. Working together, these elements reflect a reality that’s at once recognizable and dreamlike.

Ming was the first female member of the Harlem-based photography collective Kamoinge, and in 1975, she became the first African-American female photographer to have her work acquired by the Museum of Modern Art. Her work still feels revelatory.

There’s a documentary element to Smith’s work, particularly her photos of African-American urban life. But Smith is no fly on the wall. Her specific perspective transforms the people and places she observes, whether she’s photographing in New York, Senegal, Pittsburgh, Paris or Brussels.

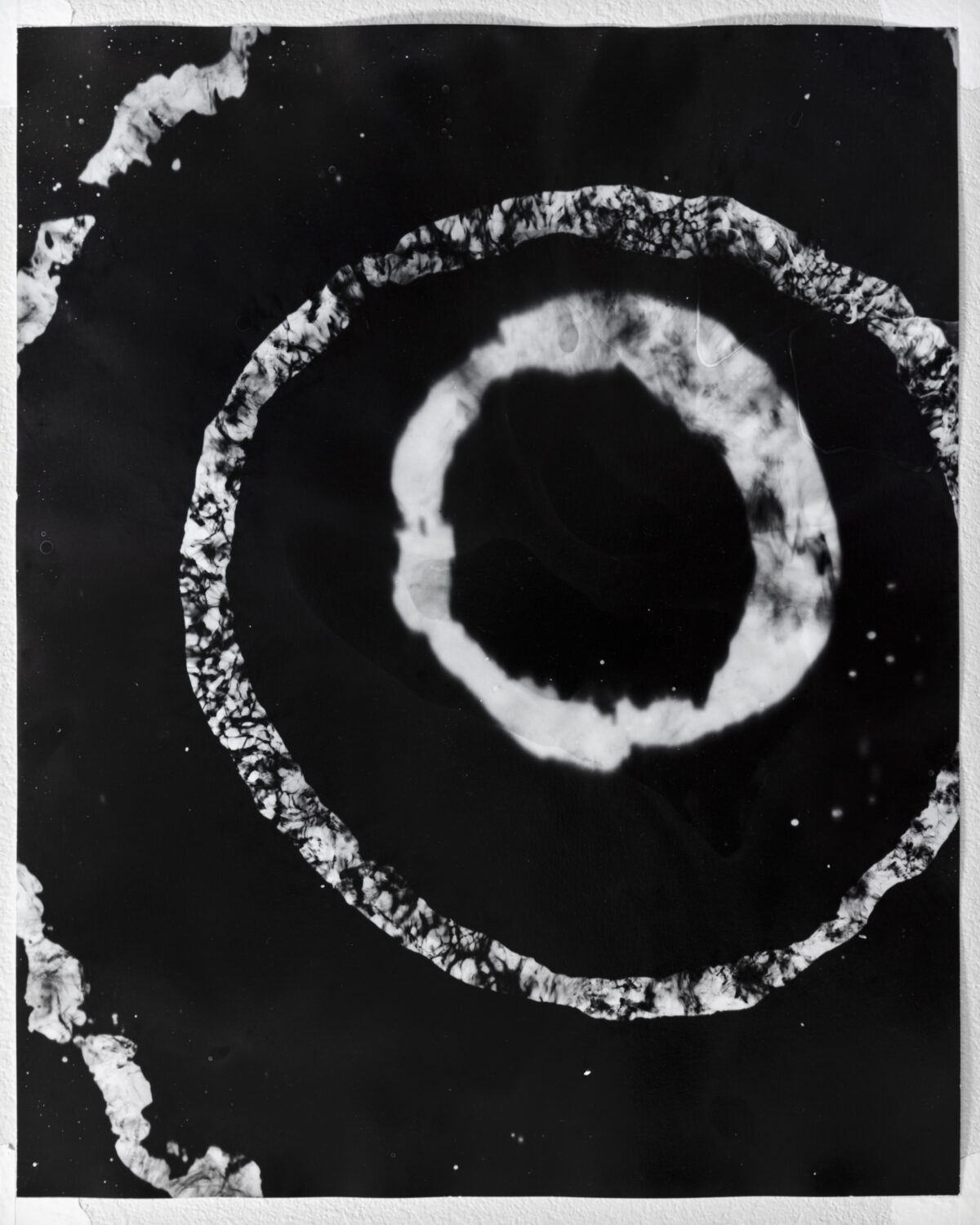

Even Smith’s most everyday photographs are imbued with a sense of otherworldliness, but others are downright surreal. In James Van Der Zee in Skies of Harlem, 1972, the visage of the African-American photographer emerges from the clouds; in another image taken seven years later, Van Der Zee is joined in the heavens by James Baldwin and Eubie Blake.

Smith’s photographs of people may be the most emotionally powerful, but her landscapes and architectural studies are striking as well. A field of sunflowers in Singen, Germany, looks apocalyptic with dark clouds overhead. Through Smith’s lens, the building in Manhattan Parallels becomes an abstraction of lines, angles, and deep shadows.

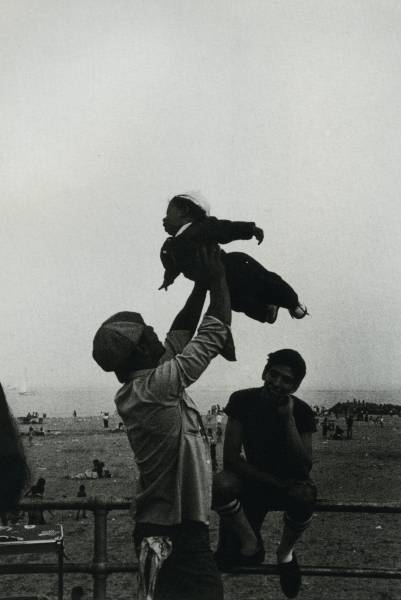

Many of Smith’s photographs highlight a sense of alienation and loss. Solitary figures frequently move through streets, suggesting pervading disturbances. And yet, moments of transcendent joy abound. In one image, black boys and girls on a chair swing at Coney Island hurtle through the sky; little of the world beneath them is visible. In the adjacent image, a young man holds an infant in the air. The child’s arms and legs are extended, face looking upwards, ready, it seems, to take flight.