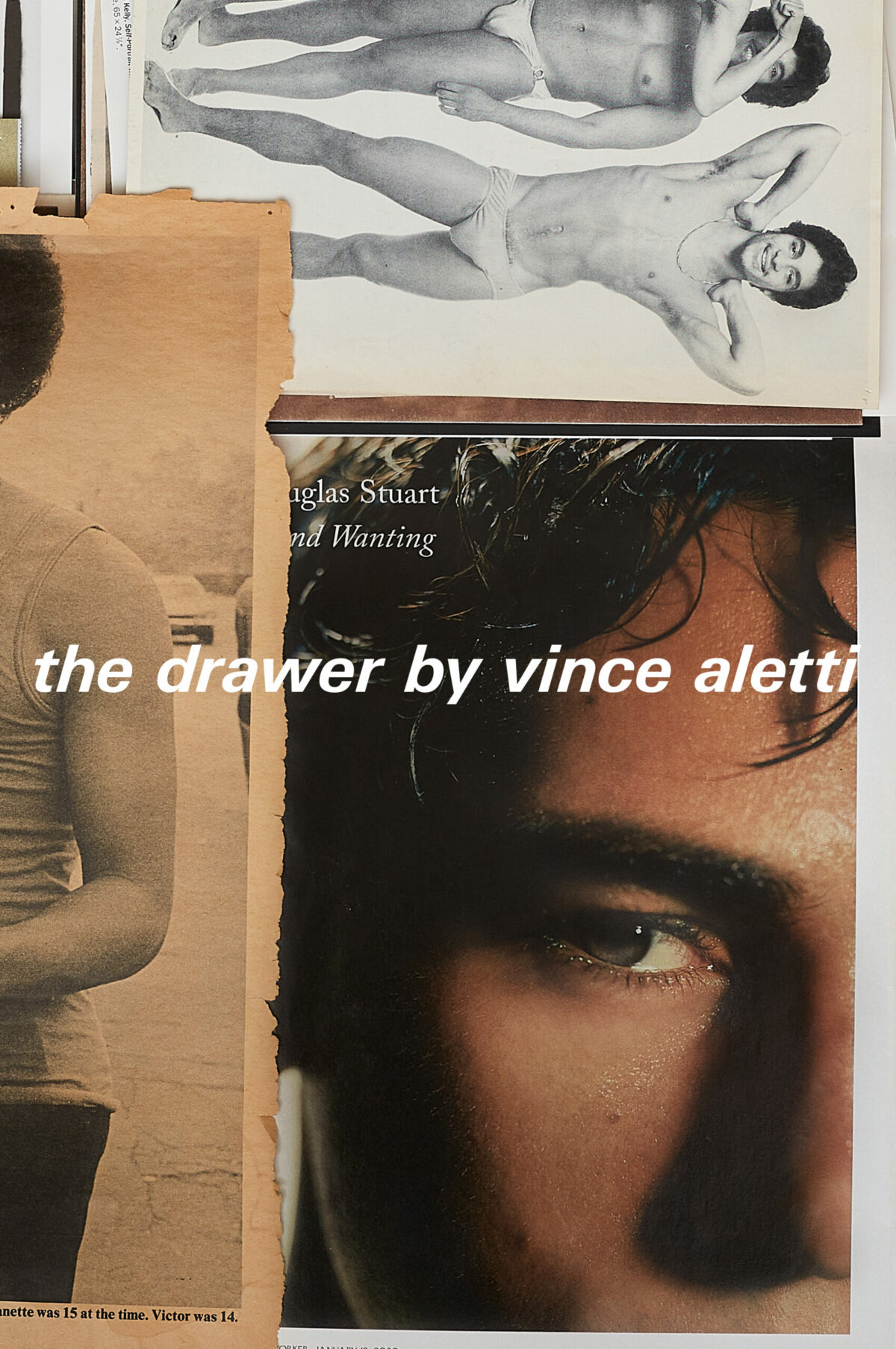

Some images are far edgier on a glossy magazine page, under a pithy headline, than they are hanging on a white gallery wall. For instance, The Gentlewoman (2010) by collaborators Inez Van Lamsweerde and Vinoodh Matadin, appeared first on the cover of Gentlewoman, a smart, small British women’s magazine. It’s a portrait of Van Lamsweerde herself as a style-conscious bearded lady. She wears a flowing white blouse with a thin black ribbon around her neck and silky black pants with a big bow around the waist. Originally, the image appeared with the words “story of the world’s best fashion photographer” below it. In that context, the image was gender-bending in a refined but still unexpected sort of way.

Hanging in the Gagosian Gallery in Beverly Hills next to a portrait of Lady Gaga as a boy gangster, the effect is different. As part of Van Lamsweerde and Matadin’s self-titled exhibition Inez & Vinoodh, on view through August 23, the image moved away from its role of compelling an audience to pick up a publication by illustrating a certain seductive sophistication. Presented in the art world, where effeminate figures with facial hair are not unsettling or unexpected – think back to Ana Mendieta and Eleanor Antin then forward to Catherine Opie and Matthew Barney — the image seems safe, its glossy prettiness adding to that impression.

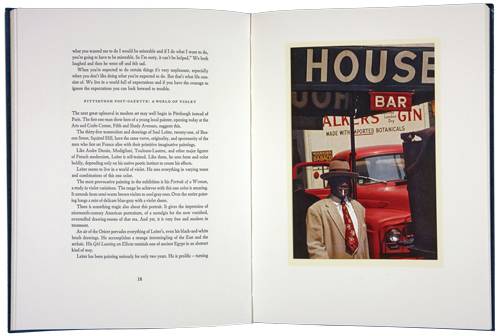

The Dutch duo has photographed celebrities or models for W magazine, V magazine, various editions of Vogue or the New York Times Magazine together since the mid-1980s and they often alter their subjects’ looks – drawing green shapes on musician Bjork’s cheeks, tangling actress Julianne Moore’s hair so that it looks like seaweed. The first galleries at Gagosian mostly feature black-and-white portraits of these recognizable figures. Moore and the late Alexander McQueen are both there, as is Javier Bardem, looking like a Greek sculpture. But the final gallery features big portraits, each about five feet across, of flowers. There are two roses standing straight up, one painted black and the other pink, or a bouquet of frosted flowers leaning across the picture plane. The duo’s competence in choosing, positioning, lighting, simplifying and visually empowering these pretty specimens is striking. That the images are well made seems ultimately to be what the show is about: the power of craft to make beauty seamless.

“We photograph whatever it is – whether it’s a human being or a flower or anything else – in its most heroic incarnation,” Van Lamsweerde said recently, interviewed by Time’s Allison Berry. At Gagosian, where heroism becomes an aesthetic, the viewer has no option but to feel awe at the image’s flawless beauty, a surprisingly unsettling experience for a viewer used to finding fissures in the surface of an image through which to enter and empathize.