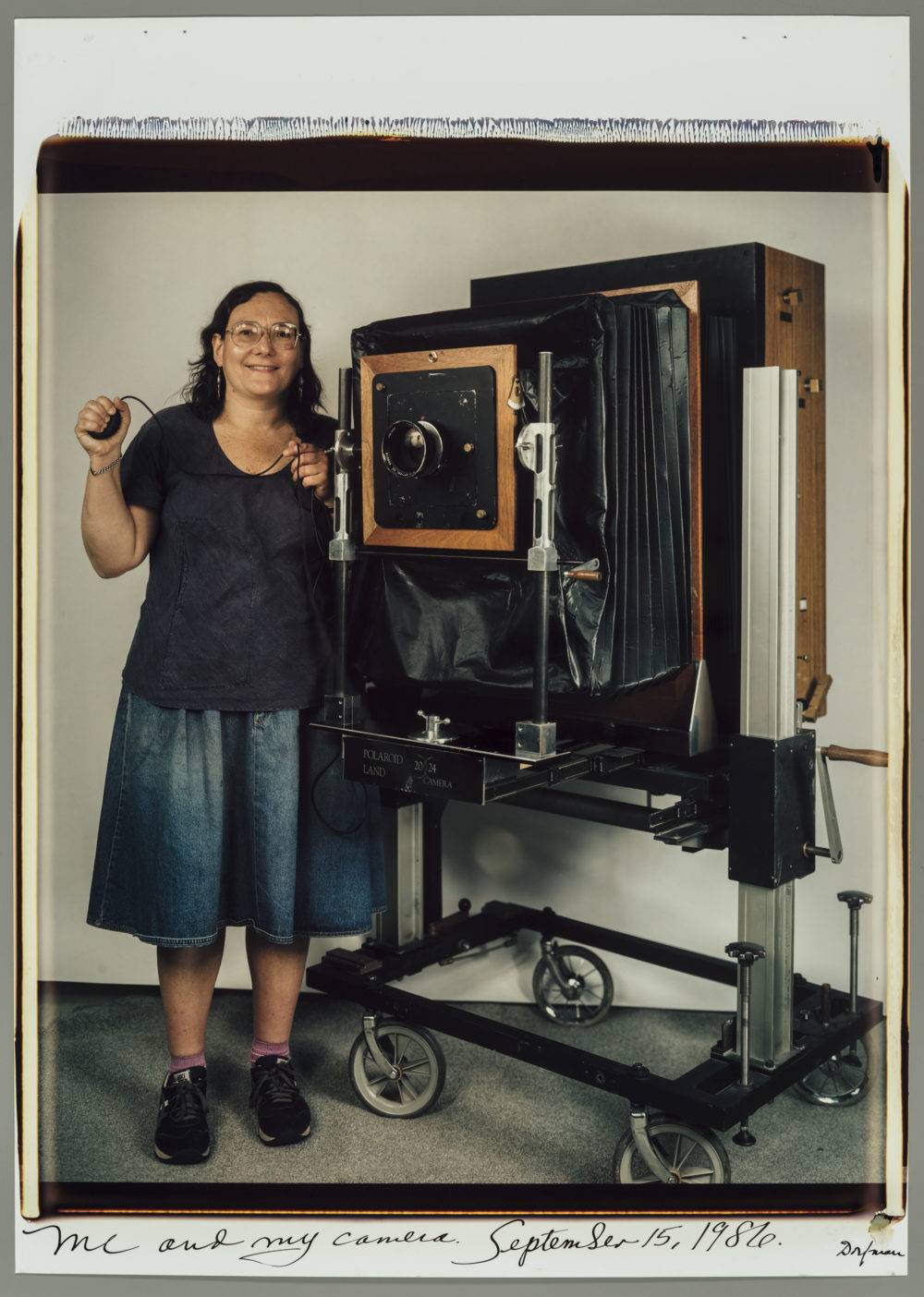

Over the course of 35 years, the photographer Elsa Dorfman has made some 4,000 portraits with the 20×24 Polaroid camera. Elsa Dorfman: Me and My Camera, which was on view at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, before the pandemic-related closings of non-essential businesses, homes in on her practice through the lens of self-portraiture. In addition to examples of her early black-and-white work, the exhibition includes 14 Polaroid prints framed in Plexiglass boxes revealing the irregular edges and chemistry residue – what Dorfman describes as the “satisfying materiality” of the Polaroid process. The overall mood is joyful: Dorfman, often wearing her signature sneakers, commemorates important events like her birthday, adding a handwritten caption underneath each image.

Dorfman describes her introduction to photography in 1965 as a miracle. In an era when it was “so embarrassing not to be anything,” including married, photography gave her an identity outside of traditional female roles. She photographed family and friends who visited her Cambridge home, publishing their portraits along with diaristic musings in Elsa’s Housebook: A Woman’s Photojournal in 1974.

Dorfman started photographing herself in the late 1960s so that “people would sense, I did it to myself too.” In On My 54th Birthday (1991), Dorfman, peering out from behind the cloud of black balloons she began receiving from her husband, Harvey, on her 51st birthday, poses with members of her family, who are in matching red pajamas and slippers. An exception to the celebratory mood of most of her photographs is I’m 60, Allen’s Dead (1997). Recalling her early black-and-white self-portraits, which were angsty and contemplative, Dorfman, unsmiling, poses nude in Allen Ginsberg’s honor, holding stalks of sunflowers while her untethered birthday balloons hang from the ceiling.

Dorfman sees herself as part of the long lineage of commercial portrait photographers who have been employing the medium since its invention, and though other artists have worked with the 20×24 Polaroid camera, it is uniquely associated with her portraits. The enormous view camera with built-in processor for developing the photographs, weighing in at 200 pounds, stands beside Dorfman like a family member or friend in three of her self-portraits and is always present through its lifeline—the ubiquitous shutter release cable.