In the hands of Dayanita Singh, the photobook is raw material, rather than an end in itself. She uses the book as a point of departure for exploring what she’s referred to as the “space between publishing and the art gallery.” To that end, her exhibition featured unique iterations of four of her “book objects:” Pothi Box, Museum of Gestures, File Room, and Sent a Letter. Singh’s riff on the ubiquitous “pop-up” store concept was part museum gift shop and part intimate cabinet of curiosities: in addition to photographs, there was a small pillow cryptically embossed “Go Away Closer,” a burgundy tunic embossed “My Life As a Museum,” glass carafes, canvas tote bags, and other vaguely talismanic mementos.

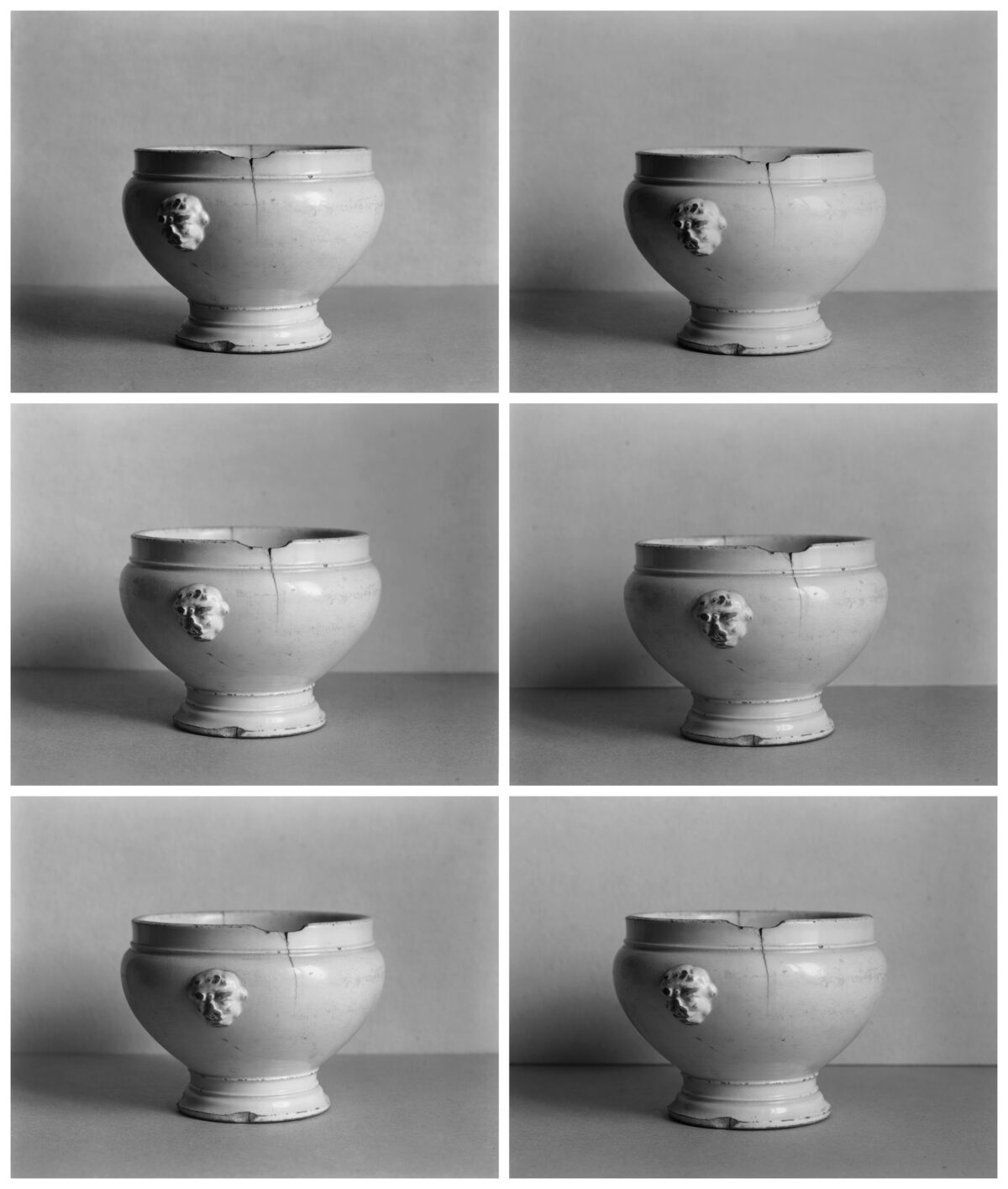

Presented for the first time was the edition Pothi Box, a set of 30 unbound, offset-printed photographs housed in a teak box. It opens on one side to form a frame and is wrapped in an inscribed linen cloth. The offset printed black-and-white photos picture a desolate paper archive, a film archive, and a printing press. Vaguely foreboding, their moldering contents convey the transience of both outmoded technology and memory itself. The image in front can be swapped out, giving the piece 30 variations, all of which were hung in a long row along one wall. It’s an ambiguous object: equal parts frame, sculpture, readymade exhibition, and archive in miniature.

Singh’s 2008 collaboration with Gerhard Steidl, Sent a Letter, is an intimate production consisting of seven small, accordion-folded photo-diaries in a handmade box. Here it was re-presented with each volume of the set stretched to its full length on a shallow shelf. The original set was thus transformed from small, privately experienced, hand-held objects – the books each measure only 4 x 6 in. when closed – into a photo-sculpture that gestures to both a temporal unfurling and to the stasis of the grid.

The through line tying all of this together is a formal and conceptual critique of the presuppositions underlying the “print-on-the-wall” and the “book-on-the-shelf:” In the short history of western fine art photography, these are privileged ways of showing photographs. Singh blurs the lines between books and exhibitions, between unique object and mass-produced commodity. In her low-tech, analog inventiveness, she has arrived at new forms of display that imbue images with a new mode of presence, more organic tone-poem on themes of history and memory than “decisive moments” in isolation.