When Brian Weil died in 1996, at age 41, art critic Roberta Smith wrote his New York Times obituary. The headline referred to him as the “Photographer Who Founded Needle Exchange,” giving prominence to his identity as a photographer. When Weil’s posthumous retrospective opened at the ICA in Philadelphia, two friends of his participated in a panel discussion. Ric Curtis, a criminal justice professor who helped Weil found the needle exchange, said he’d worked with Weil for years before knowing he was an artist. “Because everyone was an artist, no one talked about it,” said Patrick Moore, who participated in ACT UP with Weil. “There was a feeling that art was not a responsible response to the crisis.”

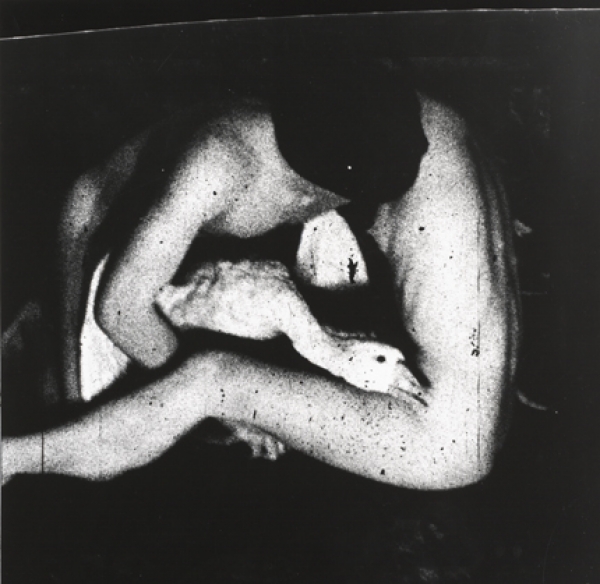

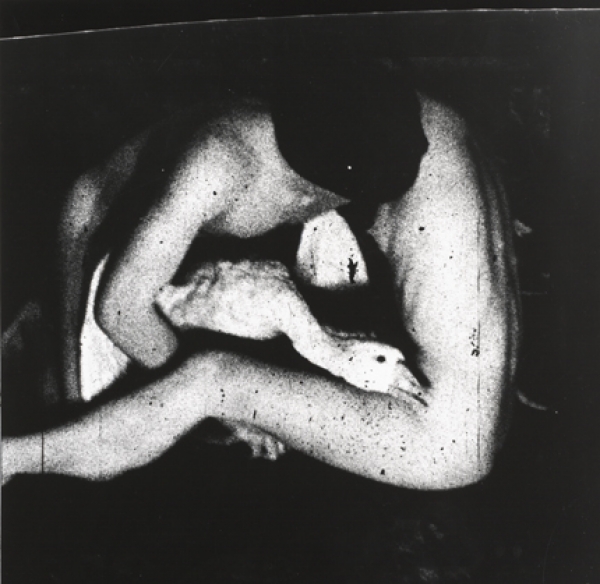

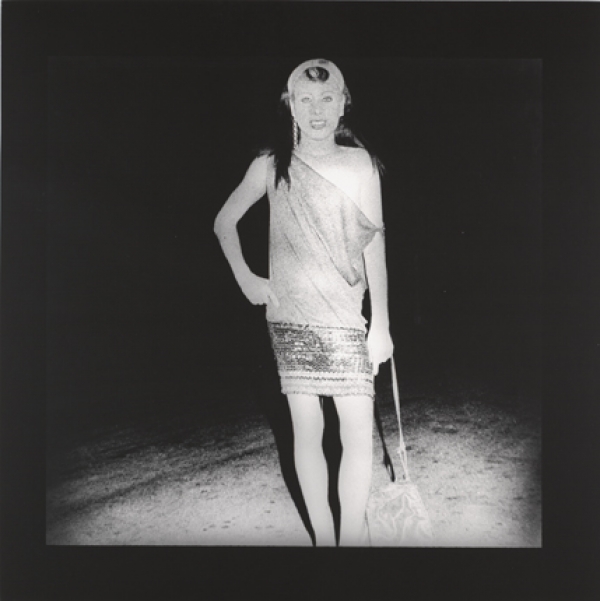

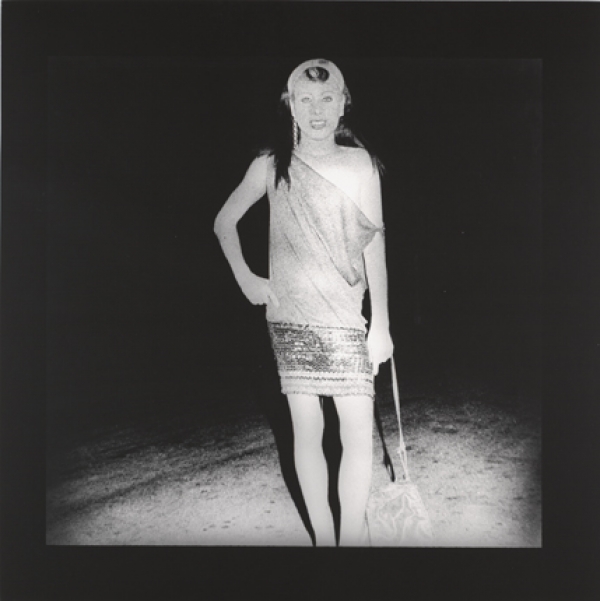

Weil’s retrospective is at the Santa Monica Museum of Art through April 18, and documentation of his activism mingles with his gritty, searching photographs of kinky sex, homicide investigations, and Hasidic communities. Showing that Weil’s art and social efforts went hand in hand is part of the show’s goal, but much of Weil’s work has an unapologetic darkness to it that contrasts with the hopefulness of his social projects. He made his black-and-white images by re-photographing Super 8 footage he had shot, then scratching and overexposing the negatives. The resulting blurry, intentionally damaged photographs give his subjects an even greater sense of mystery.

For his Sex series, Weil placed ads in the Village Voice and fetish magazines. Images include two lithe, nude bodies in ski masks — one female, one male – embracing with a goose between them. He followed homicide detectives around for his Miami Crime series, photographing over 60 crime scenes in a way that often makes it painfully clear how unprepared his subjects were to die.

This work would read as more unpleasantly voyeuristic if not for the tender documentary images of people Weil met through his needle exchange project hanging nearby. He became involved in the needle exchange work in the mid-1980s because he anticipated, correctly, that intravenous drug users would soon be hit hard by the AIDS epidemic. These images suggest that the photographer was less voyeuristic and more intensely interested in understanding how people lived, died, and fought death. As a result, the show becomes about the weird ways in which darkness and goodness coexist.